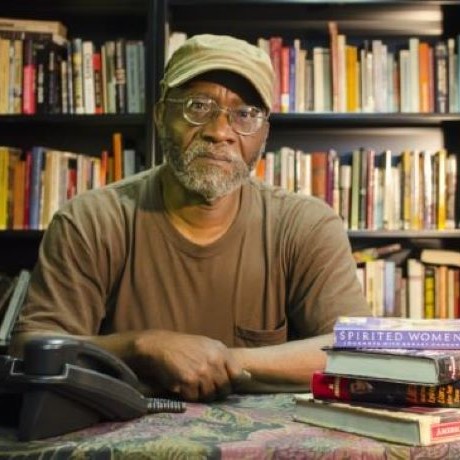

Willie Baptist (Interview 1)

The interview was conducted by Lynn Lewis, on November 19, 2018, with Willie Baptist, in the offices of the Kairos Center, at Union Theological Seminary for the Picture the Homeless Oral History Project, and is the first in a series of two interviews. Willie is a former board member of Picture the Homeless (PTH). This interview covers his approach to organizing and history with the Union of the Homeless, the formation of the Poverty Initiative, meeting PTH and engaging with the Potter’s Field campaign.

Willie describes his experience organizing in impoverished communities for over fifty years and his experience being street homeless in Philadelphia. “I’ve been poor all my life, and I’ve really become interested more in the fact that poor and homeless folks can only have any say if they’re organized and so I am committed to that.” (Baptist, pp. 3) Connecting with an organization of poor and homeless families in Philadelphia shaped him, and he worked for ten years as the education director of the Kensington Welfare Rights Union. One of their activities was setting up encampments for people turned away from shelters and housing in Philadelphia.

He shares what influenced his commitment to political education as an organizer, and contrasts that with union and not-profit styles of organizing. “I’ve learned over the years that organizing is more than moving bodies. It’s about moving minds and hearts, and that is education.” (Baptist, pp. 4) Willie describes organizing the homeless within the context of the system that creates homelessness and poverty and that protests can become a site for political education. “I mean, your involvement in protests and struggles brings questions into your mind as to why protest? Who you’re up against? Why are you up against that? Why the injustice that you’re protesting against? What’s the cause of it? These are questions that can’t be answered just by experience alone, but experience combined with education. And particularly political education because we’re dealing with a political system that upholds an economy, that thrives off of poverty and homelessness.” (Baptist, pp. 4)

Willie describes becoming aware of PTH just prior to 2004 and attending meetings at PTH, meeting leaders at PTH who were committed, including Jean [Rice] during the formation of the Poverty Initiative at Union Theological Seminary. He describes the process of joining the PTH board, and the other boards that he is a member of. He agreed to join the PTH board to play an educational role and shares some of the educational activities he led through the Homeless [Organizing] Academy.

He also reflects on the resurgence of homeless organizing nationally, particularly in connection to the Poor People’s Campaign and the value of PTH sharing its experience, “to be part of that kind of experience and know of that experience, that’s why I’ve agreed to this interview. Because I think this project—a oral history project—is very important, because there’s new players and new leaders that are emerging that need to have this experience. And one of the things I find is the disconnect of these new leaders among the homeless, among the poor—with history, with experiences. They don’t have to bump their heads against the same walls that I bumped my head against.” (Baptist, pp. 7)

He describes his first visit to PTH’s offices, “I was very impressed with the fact that you had homeless folks, men, and women, who are there planning their next action based on, I think at that time it was dealing with police injustices.” (Baptist, pp. 7) And having no doubt that homeless folks were in the leadership of that work. He shares his experience through the Poverty Initiative of working on the Potter’s Field campaign and the formation of the Interfaith Friends of Potter’s Field and PTH winning access to Potter’s Field. “But the agreement was that now people can come visit. And I remember the first visit I was on. I’ll never forget that. We was on the boat going to Potter’s Field. And I mean, it was moving in terms of Picture the Homeless and what it had done, and agitation, and education that it had carried out to bring that about.” (Baptist, pp. 8) He describes a moving experience during his first trip to the island, and sharing the story of that campaign. “I remember taking that story and that whole campaign around the country, and how people responded. I don’t care if they’re homeless or not. They just responded. And I think today, it’s something that we need to have people know about because there’s Potter’s Fields all over the country.” (Baptist, pp. 9)

He describes homelessness as exposing the direction the country is headed in, and misconceptions about homeless people and refutes those, emphasizing the growing number of students and others who are becoming homeless. He shares some of the challenges for homeless folks organizing, including internalized oppression, “I think we overcame that in our organizing of homeless folks, in the organizing. As homeless folks begin to link up and work with each other, there’s a certain strength and a certain trust that develops.” (Baptist, pp. 11) Returning to the theme of political education he stresses, “Because what I’ve learned being in education, is that the homeless are expert only in their own personal stories. “I know why I was homeless.” So, they know the effects of it, but to know the cause of homelessness, they got to be educated and trained. They’re not expert in that sense. They only know what they’ve been through, and they need to talk about what they’ve been through because it’s part of the problem, and that needs to be understood. But to understand the whole problem, that’s a political education process, which homeless folks—having been in that situation—are more inclined to understand very rapidly, because they live it! It’s not an academic discussion.” (Baptist, pp. 12) And he reflects on programs that don’t included an organizing component are actually servicing homelessness, not ending it.

PTH Organizing Methodology

Being Welcoming

Representation

Education

Leadership

Resistance Relationships

Collective Resistance

Justice

External Context

Individual Resistance

Race

The System

Tent Cities

Encampments

Political Education

Police Brutality

National Union of the Homeless

Labor

Poverty

Capitalist

Faith

Students

Tompkins Square Park

Shelter

Stereotypes

Programs

Poverty Initiative

Kairos Center

Poor People’s Campaign

People’s Forum

Dignity

Respect

Solutions

Media

Black

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Chicago, Illinois

Brazil

Salinas, California

Oakland, California

Maryville, California

Baltimore, Maryland

New York City boroughs and neighborhoods:

Harlem, Manhattan

Spanish Harlem, Manhattan

Housing

Civil Rights

Potter’s Field

Homeless Organizing Academy

Movement Building

[00:00:01] Greetings and introductions

[00:00:29] I’ve been involved with organizing for fifty-three years, in impoverished communities, spent almost a year homeless on the streets of Philadelphia, poor all my life.

[00:01:04] My concept of organization includes political education. Homelessness shaped me, met an organization of poor and homeless families in Philadelphia, setting up encampments, was education director of Kensington Welfare Rights Union for ten years.

[00:02:35] Came to Picture the Homeless (PTH) with that background, was part of National Union of the Homeless in late '80s and early '90s, gravitated toward political education, appreciate the combination of book knowledge and knowledge from life experience.

[00:04:34] Organizing is more than moving bodies, it’s moving minds and hearts, that is education. Organizing process without education is problematic, causes need to be understood, considering the role that homelessness and poverty plays in the concentration of wealth.

[00:06:23] Political education is not disconnected from protests and organizing, the protests become a school, involvement brings questions to mind that can’t be answered by experience alone. Homelessness is a big problem requiring a big solution.

[00:08:48] Became aware that homeless were organizing in NYC in 2004, heard about PTH, there was a growth of the poverty industry, people making money off of homeless and poor people.

[00:09:30] To build a movement to end poverty and homelessness you need committed clear folks, that attracted me to PTH while still in Philadelphia, met Jean [Rice]at the formation of the Poverty Initiative, now the Kairos Center, the mutual respect built with Lynn Lewis and Jean has kept the relationship going.

[00:12:24] Approached by Lynn Lewis to join the board of PTH, is a member of four boards, in an educational role. A lot of boards are set up to raise money.

[00:14:27] Resurgence of homeless organizing in connection to Poor People’s Campaign, the experience of PTH needs to be put out there, organizing homeless people clashes with the stereotypes and misconceptions that something is wrong with homeless people. This project is important for emerging leaders, they don’t have to bump their heads against the same walls.

[00:016:23] First meeting attended at PTH was on 116th St., police brutality, homeless folks trying to figure out what to do, planning, reminded me of the Union of the Homeless organizing, at PTH I saw the same qualities and potential, homeless folks were in leadership.

[00:19:27] At Union [Theological Seminary], building a movement to end poverty led by poor and homeless, met Jean, heard about the Potters Field campaign from William Burnett [PTH], talked about how the Poverty Initiative could help. Mass graves at Potter’s Field were abominable, needed to be brought out, plus PTH [co] founder was buried there.

[00:21:06] Poverty Initiative helped with formation of Potter's Field Interfaith group, after a victory people were able to visit Potters Field on Hart Island, the first visit I was on, I’ll never forget, it was moving in terms of PTH and what it had done.

[00:21:58] Someone from California heard about it and was on the boat, her sister died as a baby and mother couldn’t afford burial and lost track of where the baby was buried. She attended the service we did for Lewis Haggins, and we attended hers.

[00:24:44] It underscored the power of that campaign, maybe you didn’t get a house, but you moved people, I remember taking that story and campaign around the country, homeless or not. There are all Potter’s Fields around the country, it’s an indictment on a society that has so much, it was about dignity.

[00:26:54] PTH and the Poverty Scholars program, Jean Rice, Arvernetta Henry and Rogers were involved, homelessness exposes the direction this country is headed.

[00:28:47] Growing segment of students are homeless but there’s a false sense of security, [homeless] leaders who were part of the Poverty Initiative helped undercut a lot of belief systems about poor and homeless people.

[00:31:04] Process of supporting homeless people to speak in public, what it takes, overcoming internalized oppression, we overcame that in our organizing.

[00:33:02] As the organization grows, trust builds, people speak more, the only way to overcome the impact of corporate media is through organizing and building community. Media labelled people homeless.

[00:34:37] Homeless people know the effects of being homeless, but to know the cause of it, need to be educated and trained, understanding the whole problem is a political education process.

[00:36:38] Experience is a school that helps penetrate misconceptions reinforced by media. Organizing begins the process of breaking down insecurities, misconceptions, and internalized oppression, if programs aren’t involved with organizing they're servicing and managing it, not ending it.

[00:38:44] Key lesson from PTH is to know that people who are poor and homeless can think for themselves, speak for themselves, fight for themselves, and can organize and lead, making a way out of no way.

[00:40:17] Gentrification is a policy, folks from the middle strata are becoming homeless and poor, it appears to be a color question because people of color are concentrated in big inner cities, but no poor whites can come into Manhattan and live, it’s a class issue underneath.

[00:42:01] Revenues in big cities has diminished, they don’t want to pay for the poor and homeless, homeless folks are organizing throughout the country. I’m part of an organizing effort that includes over twelve cities throughout the country, protesting tearing down encampments, panhandling, moving homeless out.

[00:43:21] Homeless organizing is returning in a major way, you can’t have poor organizing in this country without homeless organizing, this is not a charity issue; this is an issue of justice.

Lewis: [00:00:01] Alright, so… Good morning.

Baptist: Good morning.

Lewis: Today is November 19, 2018. I am Lynn Lewis here with Willie Baptist. Willie, you are a board member of Picture the Homeless...

Baptist: Correct.

Lewis: Tell me a little bit about yourself, Willie.

Baptist: [00:00:29] Well, my name is Willie Baptist, like a Baptist church, and I’ve been involved with organizing for fifty-three years now, in impoverished communities—and I spent a spell of homelessness in the streets of Philadelphia for almost a year. I’ve been poor all my life, and I’ve really become interested more in the fact that poor and homeless folks can only have any say if they’re organized and so I am committed to that.

Baptist: [00:01:04] My concept of organization includes political education, and so I do a lot of that work and I… And so, with me, I’ve been called upon to help assist organizing efforts throughout the country… I’m committed to this stuff. This is my life. This is not what I do. This is who I am.

Baptist: [00:01:30] My homelessness was something that shaped me. Living in the streets, I was able to hook up with an organization of poor and homeless families in Philadelphia and that kind of shaped me. We were into setting up encampments, and you know—families that were turned away from the shelter system there… Came to our offices, the office of Kensington Welfare Rights Union. I was ten years the education director of that organization.

Baptist: [00:02:0] And we—one of the main activities that we would be involved with was setting up encampments, especially in periods where people were being turned away—mothers and their babies turned away—from the shelter system and from the housing department. And so, we would set up these encampments. We’d have people living on the floor—some of our members, but it would overflow invariably and so we would set up tent cities. In fact, that became our logo for the organization, “Too legit to quit.” You’ll see a tent city. If you ever see one of our t-shirts.

Baptist: [00:02:35] But that really did a lot to shape my view of homelessness and of poverty in this country, in the richest country. And so, I came to Picture the Homeless with that type of background.

Lewis: Uh-huh.

Baptist: Organizing among homeless... I was part of the National Union of the Homeless organizing drive of the late eighties and early nineties, and I’ve been involved with the homeless issue and poverty ever since.

Lewis: [00:04:17] Willie… I’m going to get to talking about how you met Picture the Homeless, but I know political education has always been really important to you—and in your own life, when did you become aware, when did you become committed to political education as an organizer?

Baptist: [00:03:28] That’s a… I don’t know—I—that’s a good question because I just kind of gravitated toward that aspect. In my fifty or more years of organizing in impoverished communities, I just gravitated more toward the educational piece. I spent three years in college, Pepperdine College. I got to appreciate book knowledge, but I also appreciated the limit of academia, because it’s basically book knowledge. I began to appreciate more the combination of book knowledge with life experience. I call it the School of Hard Knocks or the University of Adversity. And I have been very fortunate to combine that, those two sources of knowledge. So that, of the say, fifty years or more of my involvement in organizing over the years, forty of those years or more was always been my gravitating toward the educational aspects of organizing.

Baptist: [00:04:34] Now, that put me in conflict with the kind of notion of organizing I’d grown up with and have experienced. And that was—I was a trade union organizer with the Steelworkers’ Union. And also, I was involved with community organizing on the west side of Chicago around police brutality. So those are the kind of experiences of my notion of organizing. It was kind of a non-profit, staff-oriented type organizing. And in those organizing, education was peripheral to the organizing, and what I’ve learned over the years is that organizing is more than moving bodies. It’s about moving minds and hearts, and that is education.

Baptist: [00:05:21] So, an educational process that doesn’t include education—an organizing process that doesn’t include education I’ve seen is very problematic. Because the issue of homelessness is ushered from causes that need to be understood and those causes are economic and political, and they’re large causes.

Baptist: [00:05:40] And so, the concept of organizing the homeless has to be placed in connection with the organizing of a class of people who are being placed in a position of poverty and homelessness. If they’re not homeless today, they can be homeless tomorrow because that’s the nature of the system. This is a capitalistic system and it’s about exploitating and it makes money off of homelessness and off of poverty. These are big industries. This is a multi-billion-dollar industry when you consider the role that homelessness and poverty plays in the concentration of wealth in this country. So, it’s those kinds of understandings and awareness that had me always gravitate toward the educational aspect of organizing.

Baptist: [00:06:23] Realizing that education—political education I should say—is not disconnected from the actual protests and organizing, that in fact, the protests become a school in political education. It becomes a way to… I mean, your involvement in protests and struggles brings questions into your mind as to why protest? Who you’re up against? Why are you up against that? Why the injustice that you’re protesting against? What’s the cause of it? These are questions that can’t be answered just by experience alone, but experience combined with education. And particularly political education because we’re dealing with a political system that upholds an economy, that thrives off of poverty and homelessness.

Baptist: [00:07:13] It’s… Homelessness has not been abated. It’s growing. It is a big problem, and it needs a big solution, and that solution has to include, at the center, the moving of people’s thinking, along with their bodies. You know, it’s not just, “Let’s go have a protest.” Or “Let’s go have a march.” But let’s actually move people’s thinking where they become organized into a community that can make a fight for themselves and determine their own destiny.

Lewis: And so, you brought all of that kind of philosophy—organizing philosophy—into your relationship with Picture the Homeless.

Baptist: Uh-huh.

Lewis: [00:08:48] Could you tell me about when you first heard about Picture the Homeless?

Baptist: Oh, God. That’s a good question. Long before I became a board member. I became aware of the fact that there were homeless that was organizing here in New York City, just before I moved to New York City and that was in 2004. So early on, I became aware of the fact that the homeless were organizing. And my ears always perk up when I hear that poor folks are organizing themselves, because I’ve always had bad relationship with people who are organizing on our behalf.

Baptist: [00:08:36] I see this tremendous growth of what I call the poverty industry, where people make big money off—you know, have their salaries and things predicated on other people’s not having jobs or decent jobs. That is, people who are homeless and the poor. So, I’ve always been critical of that process, and always therefore gravitated toward efforts of the people who were actually hurting and affected by the problem—organizing.

Baptist: And so, that turned my attention to Picture the Homeless when I heard about it. And I remember coming to the city, from time to time coming to New York, and coming to the meetings that Picture the Homeless was having early on. I remember that. And then I was attracted to an organizer that began to convey to me a certain sincerity. Her name was Lynn Lewis!

Lewis: [Laughter]

Baptist: [00:09:30] I just know that if you’re going to build a movement to end poverty and end homelessness, you need committed, clear folks. And that attracted me to leaders of Picture the Homeless and to people like yourself, who were committed, and have certain talent about them, a certain commitment. And so, I—from then on, I observed. I became a close observer, observant of it.

Baptist: [00:10:02] I was still a member of a poor and homeless organization in Kensington—Philadelphia, in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia and I would keep abreast of the activities and the struggles that Picture the Homeless was involved in. But I did that for all efforts—you know, I remember the homeless movement in Brazil. I studied that. I kept up with that. You know, any struggle of the poor that was going on, I was always attentive. That’s because my role as an educator within the movement, within the struggle and organizing—just kind of compelled me to do that, you know—to learn from those experiences. So, I was very curious as to those experiences.

Baptist: [00:10:56] And I remember having met Jean at a certain point, when the opportunity arose for us to form a poverty program here at Union Theological Seminary. We had preliminary meetings with the then President Hough, who was very up to establishing a poverty program, or anti-poverty program, but wanted to make sure that the students were brought on. And the nature of it, we wanted to ensure that if it’s established, it’s got to be led by and connected to the poor organizing.

Baptist: [00:11:37] And so, we hooked up with Picture the Homeless and then that’s when I met Jean [Rice], and he came to the meeting. And the formation of the Poverty Initiative—now is the Kairos Center—Jean was very much a part of that formation. And we hooked up right away. I mean, we’re almost the same generation and he had been through it. I had been through it. I could respect what he’d been through, and I could respect what he had to say. And so, I think the two people that I think, really impressed me most and still about Picture the Homeless has been Lynn Lewis and Jean! And I—just… I mean we… I think there’s a mutual respect and that has kept the relationship going.

Baptist: [00:12:24] And then, I was approached by Lynn Lewis in her capacity as the Executive Director at that time, to be part of the board. And right now, I’m a member of four boards [laughs]. All of them, except for one, all of them are organizations of poor folks. I’m on the Michigan Welfare Rights, I should say the National Welfare Rights Union. I’m part of that executive board. I’m part of the People’s Forum. I just became the President of the board. I guess that’s my title, of this newly-formed People’s Forum. Now I’m a board member of Picture the Homeless. And also, I’m on the leadership council of a group in Baltimore. I’ve been working with them for the last fifteen, sixteen years, called United Workers. And so, I’m on all those boards. But my role has been largely educational.

Baptist: [00:13:47] A lot of boards are set up to raise money and funds and all that stuff. That’s not my expertise. So when Lynn approached me, I didn’t see how I would be able to play very much of a role. I was interested in what she understood my role to be, and we clicked! I mean, she wanted me to play an educational role. I said, “Okay. Cool. I’ll come on.” So I came on under those conditions. I did—with the Homeless Academy that Picture the Homeless had set up, I did a three-part course lecture to brothers and sisters there, and so, I’m very happy about that. And that was part of my educational role, how I saw my role was. But that was largely as a result of an agreement that I initially arrived at with Lynn as Executive Director of my coming on to the executive board of Picture the Homeless. Now it’s been almost seven years that I’ve been a board member, and I’m a member.

Baptist: [00:14:27] And so, now, you know—with the resurgence of homeless organizing throughout the country in connection to this Poor People's Campaign, I see the experience of Picture the Homeless. The fact that you had an organization like Picture the Homeless for sixteen years be in existence, is something that need to be put out there, because I think a lot of the propaganda and a lot of the stereotypes and misconceptions that are spread are saying that the homeless are somehow a… A problem—self-inflicted. That somehow something’s wrong with them. That —an idea of them organizing clashed with that idea.

Lewis: Uh-huh.

Baptist: [00:15:14] And so… You know, having to be part of that kind of experience and know of that experience, that’s why I’ve agreed to this interview. Because I think this project—a oral history project—is very important, because there’s new players and new leaders that are emerging that need to have this experience. And one of the things I find is the disconnect of these new leaders among the homeless, among the poor—with history, with experiences. They don’t have to bump their heads against the same walls that I bumped my head against. They can learn not to go around the wall—to go over it or go under it. But they can only do that if they can be connected with this kind of experience, which is invaluable.

Lewis: [00:16:04] Yes. Well, thank you for all that. I wanted to know if you could describe for me when you first—you mentioned going to Picture the Homeless. What the office was like, what the experience was like. Was it a meeting? What was happening? Give us—maybe give us some examples of the things that

Baptist: Okay.

Lewis: showed you that there was something meaningful going on.

Baptist: [00:16:23] Well, I remember a meeting. I was going… It was in a building. I had to go upstairs… It was an office space right next to Community Voices Heard.

Lewis: Uh-huh. On 116th.

Baptist: Yes! 116th. So I went there and didn’t know what to expect. You know, I’d heard about it… But I mean, I seen homeless folks trying to figure out what to do, planning—about particular police brutality issues, all the different issues. And that made me reflect on my experience of homeless union organizing. I was part of that homeless union organizing drive for the National Union of the Homeless. And it, you know… I was very impressed with the fact that you had homeless folks, men, and women, who are there planning their next action based on, I think at that time it was dealing with police injustices or something like, that that they were trying to deal with at that stage… I don’t know. I can’t recall all the names of everybody that was there.

Baptist: [00:17:47] But I remember very graphically that experience. That really kind of confirmed that I wanted to learn more about the experience. And about that time, the National Union of the Homeless was in a period of decline. And I was trying to sum up the lessons of why that decline. First, our ignorance. It was, you know, homeless folks who had… Three homeless males who formed this committee for Dignity and Fairness for the Homeless, which became an organizational base for the national organizing drive of the Homeless Union. So, the same people—it’s similar, I’m listening [laughs] I’m… in this meeting and I’m thinking about my work with Chris Sprowal who was the lead organizer of the Committee for Dignity and Fairness for the Homeless, and also was the lead organizer for the national organizing drive of the Homeless Union. I lived with him during the whole period—and my family lived with... He was the lead organizer.

Baptist: [00:19:00] And, you know, there was no doubt who was the leadership of that process. And when I came to that meeting with Picture the Homeless, I saw the same qualities, you know—the same potential. And I was very excited about what they were talking about and what they were planning to do, and also their history. And then… Again, that was one encounter.

Baptist: [00:19:27] The other encounter had to do with my coming to Union, being committed to building the movement to end poverty, led by the poor and homeless—and having met Jean, and him being part of the formation of the Poverty Initiative, at that time. Now it’s the Kairos Center. The nature of the work here at Union was such that we were dealing with seminarians, you know—who were preparing to become pastors and assistant pastors or reverends and getting them to commit their theology to the struggles of the poor and dispossessed, and the homeless.

Baptist: [00:20:13] Then I heard about—then I was made aware of the—one of the campaigns. I think William Burnett is the first… Was at the leadership of that campaign and we talked about how we could help—the Poverty Initiative—could help with Picture the Homeless on what I thought was a very powerful campaign. The idea of Potter’s Field and the fact that_ the indignities _that homeless folks were facing alive was being carried on in death. And the mass graves at Potter’s Field here in New York was abominable, and something that needed to be brought out. And plus, one of our founders of Picture the Homeless was buried in Potter’s Field.

Baptist: [00:21:06] And so, I remember being among the first after the victory—after we had formed, we formed—we helped—the Poverty Initiative helped form the interfaith group.

Lewis: Uh-huh.

Baptist: Reverend Amy Gopp played a lead role in that.

Lewis: Yep.

Baptist: And I remember after a certain victory that was made, that for a time there, people couldn’t go to the island, it’s Hart Island. But the agreement was that now people can come visit. And I remember the first visit I was on. I’ll never forget that. We was on the boat going to Potter’s Field. And I mean, it was moving in terms of Picture the Homeless and what it had done, and agitation, and education that it had carried out to bring that about.

Baptist: [00:21:58] But, someone from California heard about it—that they were going to make available to people who think that their loved ones had been buried in this mass grave, and she was on the boat! And she was with a minister, and we were talking, and it turned out she’s from California. And she came… And she was happy that Picture the Homeless had done this and that her mother… A long time ago her mother had her sister, who died as a baby and her mother couldn’t afford burial. And so, they… It just left the mother empty in terms of trying to find where her baby went, because she knew her baby had passed away, but didn’t know her grave or nothing like that because she was poor and couldn’t keep up with what was going on. So, she had lost track of where the baby was actually buried and so the hunch was that the baby had to end up at Potter’s Field.

Baptist: [00:23:01] So here comes this lady. She’s there in the boat, a boat that was put together, and involved a delegation that was put together by Picture the Homeless in conjunction with this interfaith group that Poverty Initiative had put together. So, I was among the first to go there with her. She agreed to attend our services that we did for Lewis Haggins, right? And we agreed to go with her. And both were moving events. They’re events that make an indelible impression on you and I associate that with Picture the Homeless!

Baptist: [00:23:37] And the event… Her event was that she brought with her flowers, and a jar of dirt. And she didn’t have enough flowers for all of us because all of us wanted to participate. And she gave petals of this flower to each one of us and the idea was that we would go to the gravesite. Of course, because it was a long time ago, the overseer of the place, of the burial site, could only point in the direction where all of the poor children were buried.

Lewis: A thousand baby coffins in one mass grave.

Baptist: [00:24:15] Yes! You remember. My memory is not as good as yours, Lynn. But that—yeah. And she, we would… She took us through a ritual, an impromptu ritual. And then, [voices breaks] even right now I feel it. She took out this dirt that she had got from her mother’s grave in California to throw the dirt in the direction. Whoo! You got to be made out of wood or steel not to feel that.

Baptist: [00:24:44] And it really underscored this—to me the powerfulness of that particular campaign and how maybe, you know, you didn’t get a house, or you didn’t get this, _but you moved people… _To the point where they have to be outraged with the kind of injustices that reflected that.

Baptist: [00:25:04] I remember taking that story and that whole campaign around the country, and how people responded. I don’t care if they’re homeless or not. They just responded. And I think today, it’s something that we need to have people know about because there’s Potter’s Fields all over the country. Every city, they’re a situation where people who can’t afford to die, which is a contradiction—in the richest country in the world and you can’t afford to die, let alone afford to live, that they have these Potter’s Fields that are set up. And I think it’s something that needs to be talked about—because I think it’s an exposure and an indictment on a society that has so much, and yet people die with nothing.

Lewis: [00:25:45] You know, the Potter’s Field campaign… At first even William was resistant to getting involved and, in an interview, says, “I was about fighting for the living, not fighting for the dead.” [Laughter] That was also kind of my orientation. And so, I was moved by members who really taught me that it was about dignity.

Baptist: Yeah.

Lewis: [00:26:13] And last weekend, I was in Baltimore with HON.

Baptist: Okay.

Lewis: At a weekend retreat and we’re using audio from this project, in the training. And in their mission statement, they talk about dignity. And so, for me, the political education that we share is also about dignity and respect. That people do have the capacity to analyze their own conditions and come up with solutions, and don’t need outside folks who don’t share those experiences to tell them what their life is about.

Lewis: [00:26:54] And so, with Picture the Homeless and the Poverty Scholars Program

Baptist: Yeah.

Lewis: that Jean Rice and Arvernetta Henry and Rogers were involved with, could you maybe share a story of how _their _participation in that moved things or made a difference or educated folks?

Baptist: [00:27:20] Well, I just think that the issue of homelessness is such a compelling issue, such an ideological factor in the life of this country—because it exposes the direction this country’s heading and it exposes the kind of justification that exists, where people can see that the issue of homelessness and poverty are charity issues. That somehow the homeless are homeless because of their own indiscretion, that they are helpless, that that’s the reason why they’re homeless. And that they can’t think for themselves. They can’t speak for themselves. They can’t fight for themselves. They can’t organize. And they can’t lead. Not just themselves, but the country.

Baptist: [00:28:08] There’s geniuses that are in the midst of this section of the population, that is growing by leaps and bounds. So, to have people like, you know, Jean and them participate in the Poverty Scholars Program was a statement to that effect. And I think for people to have a real view of what we we’re dealing with, they have to overcome a lot of the misconceptions and stereotypes that’s been deeply embedded in us, particularly people who have gone through the U.S. education system, all the way, including university—because that’s the subliminal subtext of that whole process.

Baptist: [00:28:47] Now that you have a growing segment of students that are homeless themselves, this thing of being… Is coming home to roost for them, because this is bigger than any individual. And the idea that we are here to help those homeless people, and that I’m not homeless and they’re homeless… That has to be dealt with—because the fact is, the people who are homeless, if you hear their story, they used to be where you were, and you could easily be there. It’s just a false sense of security that you can think, “Well, I’m helping them. I’m okay. I’m privileged. I’m okay.” And I think that that—I think those kinds of concepts that have been conjured up prevents a complete misunderstanding of what the problem is.

Baptist: [00:29:28] So when you have people like Jean—who knows law, been to college—this cat knows his stuff, man! He knows… He has intelligence! Yeah, he has real intelligence. He’s got the experience. He’s been around, and he can articulate these issues! And you know, on face value, you say, “Oh, this is a homeless guy… ” And you know, all the stereotypes—conjured up. But when you have leaders, as they were, part of that whole process, it just helped undercut a lot of this _deeply embedded ideological belief system _that goes beyond some of the, you know—recognition logically that that makes sense.

Baptist: [00:30:10] But it gets to the basic belief system. Because that… The notions of the poor, and the notions—particularly of the homeless, are notions that has been bom… That have been… I said, instilled in us or deeply embedded in us, that are really deep in the subconscious, because it’s something that’s constantly referenced. over and over again. Movies, TV, newspaper. Even in people that we talk to who are influenced by that, they come with views that support that. And I think it’s just a false sense of security that’s being put on people, in the sense that, “Oh, I’m doing everything right. So I’m safe.” No, you’re not safe.

Baptist: [00:30:47] And the actual organizing and also the actual participation of people from the ranks of the homeless undercuts that notion.

Lewis: So, you’re talking about people who are homeless representing themselves.

Baptist: Right.

Lewis: [00:31:05] As an organizer, I wanted to ask you to speak to that process. You know, you’ve got somebody who is homeless and you as an organizer are inviting them—or pressuring them—to go, “Here’s the mic. You speak.” Is that a simple process? What does it take?

Baptist: Well, it’s not simple because there’s a certain internalized oppression and an internalized misconception—even of yourself as a homeless person. That somehow, you’re a failure. That it’s something to be ashamed of, and that it’s not your place to be able to speak to these issues. So, you have to overcome a lot of that.

Baptist: [00:32:00] I think we overcame that in our organizing of homeless folks, in the organizing. As homeless folks begin to link up and work with each other, there’s a certain strength and a certain trust that develops that you’re not going to be—played with, or the fact that you’re homeless is not going to be manipulated, make you think even worse about yourself. So you’re kind of quiet for a while. But in that organizing and the trust building… And you’re having to have them speak as they never have spoken before about their homelessness, something that they know—why they’re homeless. They know that. And so, it’s easier for them to talk about their own homelessness. So that’s the first step.

Baptist: [00:33:02] But as the organization grows, and the trust builds, and you begin to speak more, people can speak beyond just themselves. I think… The impact of media, especially corporate media, is so strong, that to overcome that, you can only overcome it through organization, and through building community. And in that, you see people beginning to find themselves.

Lewis: Uh-huh.

Baptist: [00:33:36] Now, I think one of the big problems we have is defining homeless and homelessness, because when we were organizing, one of the organizing, in the eighties and nineties, it was corporate media that labeled people who were homeless, homeless people. The term homeless people came from corporate media, not from the homeless themselves. So, the notion of a homeless person is narrow and defined.

Baptist: [00:34:05] You show me a homeless person or have them to talk about their lives, and they’ll tell you they have—there’s problems with jobs, there’s—they have family. They have all They’re not just homeless people, almost like Black people. You can’t stop being Black. So, the notion is, you know—what the corporate media was able to project, is this notion that this is something separate from you. It’s just those people over there. There not… There’s something wrong with them. And I think with the… It’s only through the organizing where you can begin to confront and define that—what does homeless mean.

Baptist: [00:34:37] I think the… Educating people, and particularly the homeless… Because what I’ve learned being in education, is that the homeless are expert only in their own personal stories. “I know why I was homeless.” So, they know the effects of it, but to know the cause of homelessness, they got to be educated and trained. They’re not expert in that sense. They only know what they’ve been through, and they need to talk about what they’ve been through because it’s part of the problem, and that needs to be understood.

Baptist: [00:35:06] But to understand the whole problem, that’s a political education process, which homeless folks—having been in that situation—are more inclined to understand very rapidly, because they live it! It’s not an academic discussion. It’s something that they live. So, the… Having homeless folks who are part of a process, being able to articulate and be part of the organizing process, really advance that process and it undercuts this powerful influence of corporate media.

Baptist: [00:35:43] You know, now, when you get to Jean, for example—he has, like everybody—he has his shortcomings. But he has his real strengths, and you get to appreciate those strengths. And then that orients you toward the problems of homelessness that get at the root of it, and not with the manifestation of it or the effects.

Baptist: [00:36:03] And so, the untold stories, not only the untold stories of the effects of the homeless talking about their personal experience, but the untold stories of the cause, of it. That is what organizing and education, has to be about and that’s what I’ve come to learn. I think in that process, the working with people who are hurting and not for them is a necessary ingredient in that political education process. It really helps break through the deeply embedded stereotypes.

Baptist: [00:36:38] You know, I think there’s something about experience that is more of a school that helps penetrate these long-held misconceptions that are constantly reinforced by media. Is that when you actually have to experience, work with, and in connection with, or even go through an experience where you are homeless and you’re taking up organizing, you’re taking up protest, that begins the process of breaking down a lot of the insecurities, and misconceptions that you—and internalized oppressions, that you have. And it’s necessary, because those misconceptions that you have even of yourself—paralyze you.

Lewis: Yeah.

Baptist: [00:37:21] And so to organize means to break that paralysis. That’s why I think a lot of the programs around the problems of homelessness and poverty… Are programs—if they’re not involved with organizing—means that they don’t really understand homelessness. They don’t understand the cause of it and why you need to organize, and why just services or helping out here and there is not about really solving the problem of homelessness. It’s servicing it. It’s managing it. It’s, you know, it’s not ending it, you know?

Lewis: So we have a couple of minutes left. If we… If I could just ask you to reflect on something you mentioned in the beginning of the interview, or maybe even before we started recording. And that is that all around the country, there’s homeless folks organizing, attempting to you know—survive and even thrive. And that Picture the Homeless is one of the oldest groups, actually the second oldest after San Francisco. What do these newer groups have to learn from Picture the Homeless? What do you think the lessons are?

Baptist: [00:38:44] Well, there’s… I think the key lesson for everybody, not just the homeless folks, is to know that people who are poor and homeless can think for themselves, can speak for themselves, can fight for themselves, can organize for themselves, and can lead. Not just themselves, but the whole country. And there’s a huge reservoir of genius out there. Because, you know, the process of thinking involves more than just quoting scriptures or quoting a book. It involves the manipulation of your thinking to figure out how you can make a way out of no way! That’s the position that poor and homeless people are put in. So they have to constantly use this intellectual capacity that they have. And so, there’s a lot of examples that comes out in the course of the struggle of the homeless that just totally challenges people to rethink this question—in a much more profound way than just superficial.

Baptist: [00:39:48] The problem of poverty and homelessness is continuing, and it’s become—it’s globalized. I mean, the problem is on that scale. So if you’re going to solve a big problem, you got to have a big solution. And there’s a potential for that big solution, because everywhere, worldwide, but even in this country, the homeless and the poor are under attack, especially in these big cities.

Baptist: [00:40:17] I see the pattern of gentrification has become a policy—in the sense that there have to… For any society—Aristotle pointed this out a long time ago, that for any society to be stable—it has to have a large middle strata, has to have a large middle strata. But what’s happening is that this crisis that we’re facing, is dismantling whole sections of the middle strata. And you’ll find some of those folks among the homeless ranks and among the poverty ranks.

Baptist: [00:40:42] That’s what… That’s the direction that the country’s headed. That’s why this idea that, “Oh, it’s about you guys. I’m going to help those people.” No! This is about the direction that the country is heading! So organizing the poor and homeless, and for them to organize themselves against these attacks, which has been accelerated with the gentrification process. Gentrification means attacking the poor. That’s what it is.

Baptist: [00:41:12] And it’s not… It appears to be a color question because of the concentration—in terms of demographics—of poor and of color in these big, major inner cities. But now that they’re having to bring in higher incomes, so as to support a diminished tax revenue, they’re having to move on the homeless and the poor—and since they’re mostly poor Blacks and Hispanics, people think of it only as a color question. But you know, there ain’t no way a poor white can come into Manhattan and live. So, it’s a class issue underneath and the powers that be who have taken this on as a policy throughout all the major cities worldwide—you see the same thing happening.

Baptist: [00:42:01] The economy has reached a point where the revenues in these big cities have been diminished, and so they have to supplement that. And the last thing they want to take from their diminished revenue is to pay for the poor and the homeless. So, you see this direction—of pushing the homeless and the poor out of these communities. Like right here—at Columbia University. They’re evicting Harlem! Spanish Harlem and Black Harlem. And that’s all part of a process that every major city is happening. And the most vulnerable to that, of course, is the homeless element. So, the only counter to that is organizing, and homeless folks throughout the country are indeed organizing.

Baptist: [00:42:44] I’m part of an organizing effort that now includes over twelve cities throughout the country—that are formed, are organizing among the homeless. And some of the effort has to do with… Protesting and blocking the city from tearing down their encampments—like in Oakland, or in Salinas, in Maryville… Also has to do with panhandling, the ordinances that are being tightened up, so as to move the homeless out.

Baptist: [00:43:21] So the homeless organizing is beginning to return, in a major way, and also poor organizing connected to that, which the homeless as poor are part of it. But you can’t have poor organizing in this country without homeless organizing, because that’s at the forefront. And so, you have this rekindling of an organizing drive just because the situation is becoming much more excruciating.

Baptist: [00:43:45] And also it is involving more and more people who were once middle class, working class—and now they find themselves poor and homeless. And they’re bringing with them certain organizing skills, because you have situations like with the Poor People's Campaign that’s going on right now. You have SEIU trade union organizers who are living in their cars! Huh? You know? I mean, this is the predicament. So this is not a charity issue. This is an issue of justice.

END OF INTERVIEW

Baptist, Willie. Oral History Interview conducted by Lynn Lewis, November 19, 2018, Picture the Homeless Oral History Project