Rogers

The interview was conducted by Lynn Lewis, on January 18, 2018, in her apartment in East Harlem with Rogers for the Picture the Homeless Oral History Project. Rogers joined Picture the Homeless (PTH) in 2001, and became active in the Civil Rights and Housing campaigns, and was a founder of the Potter’s Field campaign in 2004. This interview covers his early childhood, his life as an activist, experiences in the NYC shelter system as well as during periods of street homelessness in Harlem, and his experience with PTH.

Rogers was born in Trinidad, where he lived the first eleven years of his life attending Catholic school. He describes his life until around age fourteen as a middle-class immigrant experience. After migrating to the U.S. he lived with his parents and brothers in Elmhurst Queens, attending Catholic school and living what he describes as a middle class immigrant experience. It was the first time he was surrounded by majority white classmates and upon arrival to the U.S., he had to repeat sixth grade for the purposes of acculturation, and was scarred by that. He was intellectually curious, “I was more than curious in terms of the religious aspect because I had seen Catholicism in one form in the Caribbean and I was alert to the differences. I was alert to nuances of Catholicism in the U.S. of A., and some of the things that were different. Not the least of which is that, in the United States and in Queens County of New York City—in the mid-sixties—it was a rare thing to see a priest who looked like me. There were not many Black priests in our diocese and our church.” (Rogers, pp. 4)

Rogers mother was a dietician, and his father was an optician, who was subjected to racism at work. Rogers associates this with his father’s drinking. “That would anesthetize some of the pain of being the second Black employee of Sterling Optical and being a trained and competent professional who was never recognized as such by his employers. He was a boy to them, though he was twice, sometimes three times their age.” (Rogers, pp. 6) His parents worked to bring their four sons to the U.S. to enjoy a better life and that coming from a country that prized literacy and education gave him confidence, but made it difficult for him to accept be stereotyped as a “ignorant West Indian.” (Rogers, pp. 8)

East Elmhurst was a place where people cherished education and their heritage, a birthplace of the Black Panthers, and other community members who encouraged young people to take pride in things not taught in school. Mr. Cecil Paris had a significant impact on him and others at school and the community, “Well, he understood the importance of children having a cultural grounding. That was something which was antithetical to what the white Christian clergy saw and felt was a good education. They wanted us to know and to memorize the works of Robert Frost or something like that. We were a little bit more concerned with understanding who the people were of North Africa, and who Haile Selassie was, and why he became famous. That was our priorities contrasted with theirs.” (Rogers, pp. 10)

He struggled with the racism of the Catholic Church as a teen, and reflects on his analysis that celibacy and abstinence were false and unreal. He was deeply impacted by attending a meeting of the Conclave of Cardinals from around the world. “When I heard the African Cardinal stand up and speak out about racism within the Church, I realized, “Hey, I’m not the only one who saw this.” When I heard them speak about how the vows of celibacy are contrary to the laws of nature, that was something that was in my own head. I said, “Oh, the African cardinals are speaking my thoughts.” That was an eye-opening moment.” (Rogers, pp. 11)

Attending NYU, he says, “It put me in the mix. Everything from people who were regular reefer smokers, to people who were homosexual, to people who were ex-prisoners. All of that was in the mix of a college, a university and that’s what, to me, a college, a university is supposed to be. A very, very, varied mix of peoples out of which there’s some resonance of truth in certain ideas. We could learn from each other as well as learn from the academic core.” (Rogers, pp.12) He became involved in the Curcia and Focolari movements, which taught the critical role of laypeople in the Catholic Church, and he continued to explore how to serve God and his community and describes the political context of the mid-seventies.

Moving to Harlem in 1999, he attended community meetings where he was introduced to PTH. He describes Harlem’s political context and colleagues who had an impact on him and his social justice work, including around housing, caring for children, domestic violence, employment discrimination, racism. “We can’t just sit still, and say nothing, and do nothing. We’re commanded to do something in the face of this injustice.” (Rogers, pp. 17)

Become homeless in the late ‘90s, “the group that I felt was fighting for justice, speaking for and on behalf of the homeless, and doing the things that I saw or heard as God’s commands, that was the Picture the Homeless people! It’s like, ‘Okay, if these people are doing the same thing that I’m doing, then maybe I should be doing it with them, as opposed to being a lone wolf someplace.’” (Rogers, pp. 18) He describes his experience in the shelter system at Camp LaGuardia and how he secured housing on his own, with no assistance from the shelter staff and he shares his experience with street homelessness, sleeping in Marcus Garvey park in Harlem, his encounters with the police and homeless folks supporting one another to stay safe, as well as how improper signage would lead to tickets and arrests in the park. “The signs were not always in agreement and were not always posted. So, I would get the tickets, and every single time I got, I ended up sometimes spending the night in jail. It was a warm place to stay so that certainly met my needs. Then the charges would be dismissed the following day.” (Rogers, pp. 28)

His experience of working on the Potter’s Field campaign connected with his religious beliefs, “As I learned about the horrors that happened on Hart Island and the million souls that are buried there, it became important to me to understand that this severing of the people who are buried there from the rest of the church community is ungodly.” (Rogers, pp. 30)

He reflects on his experience and analysis of PTH’s vacant property count, “Common sense says that if we have, on the one hand, a hundred thousand vacant units, and on the other hand, eighty thousand homeless people, there should be some way to put those two things together. That’s common sense.” (Rogers, pp. 31) While he celebrates the passage of the Housing Not Warehousing Act, he acknowledges the importance of making sure the law is implemented. “We still have to fight to make sure that the vacant spaces are converted into decent places for people to live.” (Rogers, pp. 32) And he asserts that “It is completely doable that every single person in New York City can have a decent place to live and convincing those who would do the task that it is doable is part of we continue to have to do, you know. Convincing city council people, convincing some real estate owners, convincing some developers, this is what we have to continue to do.” (Rogers, pp. 33)

PTH Organizing Methodology

Being Welcoming

Representation

Education

Leadership

Resistance Relationships

Collective Resistance

Justice

External Context

Individual Resistance

Race

The System

Black

Immigrant

Church

Culture

Stereotypes

Literacy

Empower

Radical

Police

Neighborhood

Gentrification

Harlem

Bystander

Vacant Property

Developers

Politicians

South Quay, Port of Spain, Trinidad

Barbados

New York City boroughs and neighborhoods:

East Elmhurst, Queens

Bronx

Harlem, Manhattan

Housing

Potters Field

Civil Rights

Homeless Organizing Academy

Organizational Development

Movement Building

[00:00:05] Introductions, member of Picture the Homeless since the early 2000’s.

[00:01:16] Middle class immigrant experience, born in Caribbean, emigrated to U.S. at age eleven, attended Catholic School, surrounded for the first time by majority white classmates.

[00:03:17] Scarred academically, emotionally and socially by having to repeat the 6th grade for “acculturation to the American way of life”. He read voraciously, was a precocious eleven-year-old.

[00:05:38] Learning as much outside the classroom as inside, dismayed at lack of ambition and intellectual curiosity by many of his classmates.

[00:06:20] Very curious about differences in Catholicism between the Caribbean and the U.S., in the mid 1960’s, it was rare to see a Black priest in his Diocese in Queens, if they did, they were African, visiting for seminary although it was commonplace back home.

[00:08:11] Lived in E. Elmhurst, Queens, a black middle-class community. There were wonderful people there, among them was Mr. Cecil Paris, the kind of man he aspired to be. He had a great impact on him during his teen years. His granddaughter, Anika Paris would later work at Picture the Homeless.

[00:11:40] Mr. Paris didn’t work at the school, but had the ear of the principle. Black children were overlooked by the white clergymen and nuns when it was time for enrichment activities, Mr. Paris spoke up and made sure that Black children attending the school had the same opportunities and that their spiritual growth was attended to.

[00:14:52] Description of childhood home and family life. Mother was a dietician and father an optician, he had four brothers. Father was the second Black employee at Sterling Optical, where he suffered from racist treatment.

[00:17:47] Experience of parents moving to the U.S. and preparing a life to bring their children.

[00:18:59] In Trinidad, family lived in South Quay, Port of Spain. There was always a meal if someone didn’t have, folks would step in and help. Trinidad was second only to Barbados in literacy levels, at some point, in the world. Education was of paramount importance. There were no illiterate adults.

[00:22:17] Confident in his educational background and knowledge, in contrast with the views of his classmates and teachers in the U.S. who spoke of illiterate or ignorant West Indians, he would challenge them on that.

[00:24:37] Trinidad, kinship of family and friends, weather, celebrations of people, history, and culture. He was able to hold onto some of that with other folks from the Caribbean in New York.

[00:25:53] East Elmhurst was the birthplace of the Black Panthers in NY, who also cherished education and heritage which took place outside of school, in the community. The Langston Hughes Library in Queens was a place for study of African culture and heritage.

[00:29:45] Brooklyn was a cultural feast in terms of Caribbean culture which connected to the educational interests of Caribbean families for their children in contrast to the educational priorities of the white Christian clergy.

[00:30:41] An awareness of the world beyond the U.S. or Euro-centric culture, the importance of children having a cultural, global grounding, Africa.

[00:31:36] Siblings participated and worked to enjoy their cultural heritage, brother one of the founders of the NYU Steelband.

[00:34:14] Racism within Catholic High School, differences between the Catholic Church as it was manifested in the Caribbean and how it manifested in Queens, understanding how racism existed within the leaders of the Catholic Church. Deciding not to pursue the priesthood.

[00:37:19] Attended the Eucharistic Congress of Cardinals, a life changing experience. African cardinal denouncing racism within the church as well as celibacy was an eye-opening moment, and part of his spiritual growth, seeking people of like minds.

[00:38:39] Connecting with African Cardinals whose views of the Catholic Church aligned with his, understanding Africans were criticized, ignored even punished for differing with the Pope.

[00:40:46] Importance of mentorship, Mr. Cecil Paris.

[00:42:12] Attending NYU, seeking an experience with a varied mix of people to further his education, active in the Institute of Afro-American Affairs at NYU, making sure that Black students were heard. Greenwich Village was a bigger world than East Elmhurst, Queens.

[00:44:36] Participating in the Curcia Movement and the Focolari on weekends, empowering lay people to minister to other laypeople within the Catholic Church was significant in his growth and development.

[00:47:14] The role of college, the Church and peers in helping to identify his niche in the adult world.

[00:48:07] Greenwich Village, an environment of free sex, pot smoking hippies, fellow white students having family conflicts around race including those from liberal families, some shocked at the racism faced by people of color.

[00:53:05] Recognizing the things that will bring him closer to God and what things take him away from God, the importance of choosing to do the right thing in terms of faith and politics.

[00:56:13] First learning about Picture the Homeless, likely from a clergy person, low level community politics in and around Harlem. 1990’s and early 2000’s. Moving to Harlem in 1990.

[00:58:27] Harlem during the 1990’s, El Barrio was a political melting pot, left wing radicals, multi-racial. Continued involvement in political and Church work.

[01:00:02] Ongoing alignment with political and church work, the Council of Black Catholics, being labelled left-wing radicals, Laura Blackburn.

[01:02:02] Fighting for integration and fair housing laws, meals in schools for children, supporting victims of domestic violence, police brutality, being labelled as a left wing radical, the coming together of Church and politics.

[01:05:13] We’re commanded by God to do something in the face of injustice, a middle-class lifestyle increasingly became less important than choosing to serve God, had to make choices to participate in the fight for justice, the importance of not being a bystander.

[01:06:28] Necessity of supporting others in social justice work, that they know he supports them, it’s not crazy lunatics doing this work.

[01:07:31] Attending neighborhood meetings, encountering Picture the Homeless in Harlem, political consciousness awakening, gentrification.

[01:09:45] Becoming homeless in late 1990’s, the group that was fighting for justice was Picture the Homeless, he chose not be a lone wolf but to connect with Picture the Homeless and likeminded people fighting the same fight.

[01:10:38] Committing to Picture the Homeless because they were talking about the same thing he was seeing, fighting for everyone not just for themselves.

[01:13:42] Bellevue and Camp LaGuardia men’s shelters.

[01:14:41] St. Mary’s Church, the [Harlem] Tenant’s Council, the National Action Network, sties where he attended community meetings, events, actions.

[01:17:13] First impressions of Picture the Homeless, Harlem gentrifying and homelessness increasing, the two are connected, speaking out against profit minded realtors a necessity, enough people weren’t organized, Picture the Homeless was doing this better than anyone else.

[01:21:07] Camp LaGuardia, organizing a shelter residents chess tournament, process of getting an apartment, staff didn’t help, the shelter made more money if people stayed in the shelter.

[01:22:31] Doing all the work to find housing from within the shelter system, the staff did nothing, not motivated to help shelter residents find housing, their salaries depending on more bodies in the beds.

[01:25:01] Description of shelter/Camp LaGuardia, an hour outside of New York City, travelling by bus every day from Bellevue Men’s Shelter to upstate Camp LaGuardia, being a shelter resident and a volunteer at Camp LaGuardia, eventually earning three dollars a day, witnessed the process when shelter residents passed away.

[01:30:19] Staff not assisting shelter residents to get housing, frustrated by some homeless men who didn’t do more to find their own housing.

[01:33:03] Had applied for Section 8 even before he went to Camp LaGuardia with assistance from someone at a soup kitchen, after moving into an apartment in the Bronx, he continued to help people fill out housing applications, sometimes resented by shelter staff.

[01:37:52] Travelling back to Camp LaGuardia and other shelters with Picture the Homeless, sharing information, policy conflicts with the City around placing shelter residents in communities where they come from.

[01:40:20] While homeless, there were times that he slept on subways and in Marcus Garvey Park, finding safety with other homeless folks, police harassment, threats were from the police not drug dealers or sex workers.

[01:42:11] Poor signage about curfews leading to arrests of homeless people in Marcus Garvey Park at night, use of in defense in court.

[01:43:01] Homeless people getting tickets, or arrested and being put through the system by the police for being homeless and in the park after curfew, depending on who the arresting officer was.

[01:45:24] Homeless folks relying on one another for safety, sleeping in shifts, sharing information, sleeping in parks, atriums, relationships with security guards.

[01:47:41] Participating in the founding of The Potters Field campaign, convergence of faith, politics, a natural outgrowth of Church life to work to allow people to grieve and commend their loved ones to God. It was a blessing to do that work and meet magnificent people.

[01:50:48] The way the burials took place and not allowing visits to the million souls buried at Potter’s Field placed his faith in direct conflict with the rules of the municipal authorities.

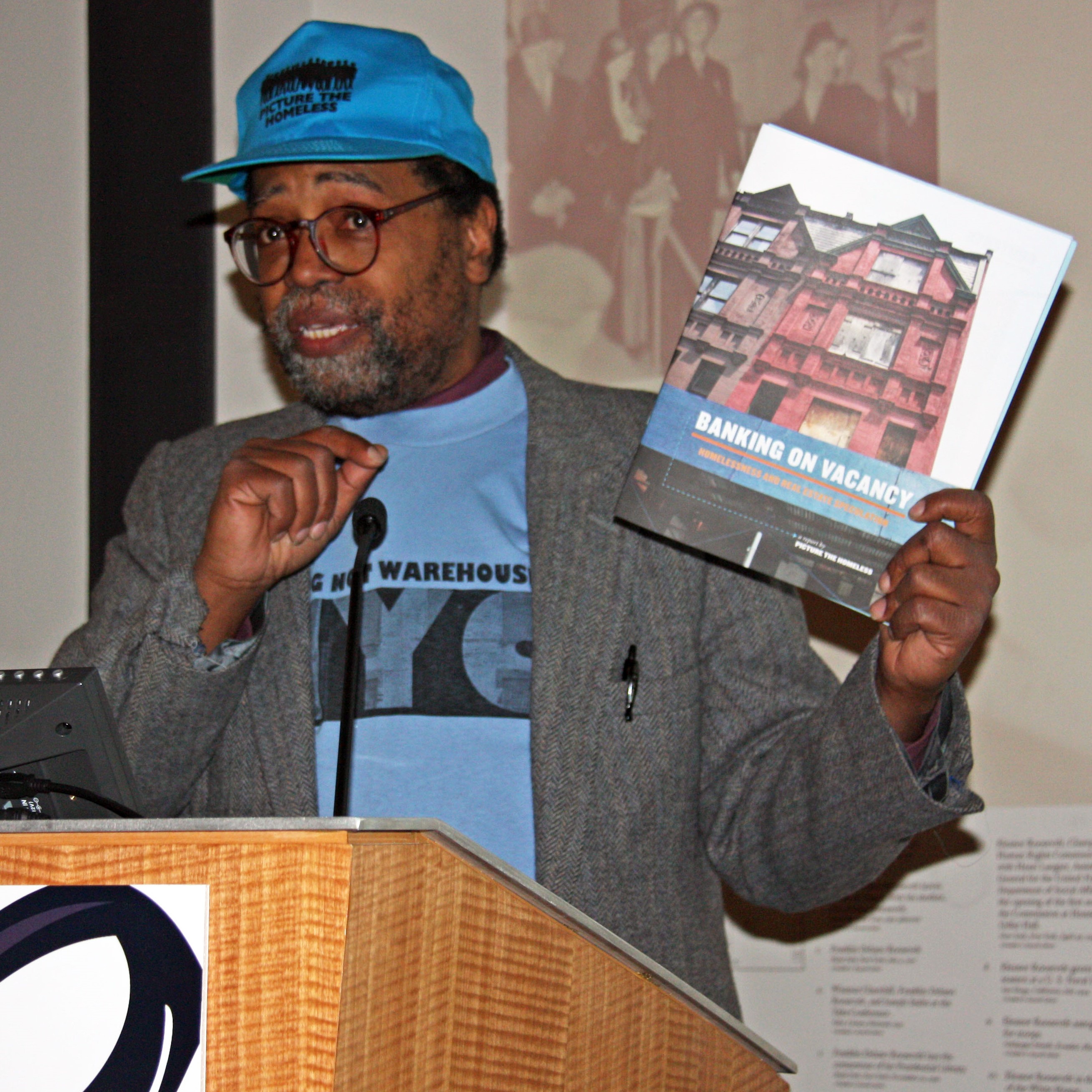

[01:54:01] The Picture the Homeless Manhattan Vacant Property Count, sleeping out in the rain, counting vacant property to the signing of a law mandating the city do so.

[01:54:57] Common sense shrouded by political motives, politicians standing between people who need a place to live and vacant space that can be homes.

[01:56:03] Politicians may not be evil, profit may be the evil that motivates them. The contradiction between people who need a place to live and the fact that there are vacant spaces, the two can be put together and the politicians stand in the way. It is our obligation to speak to power.

[01:57:25] Vacant property count, moving some members of the city council to see the ease with which homeless people can be domiciled. We have to continue pushing, it’s not rocket science.

[01:59:21] Passing a law is a step forward, we need to make sure it’s implemented. The vacant property count in 2006, converting vacant spaces into homes for people to live rather than the bureaucratic and expensive homeless shelter system.

[02:01:04] Motivation to stay with Picture the Homeless. It is possible for every single person in New York City to have a decent place to live, obeying God’s commandments, being true to God, not dying a hypocrite, housing the homeless is critical.

[02:03:14] New York can’t be the greatest city in the world if its people have nowhere to live, faith tells him it’s something we must do.

Rogers: [00:00:05] I will be just using my surname throughout.

Lewis: Okay. So, we are recording, and I’ll be checking the sound levels here and there. Today is January 18th, 2018, and we are here in my apartment. I am Lynn Lewis and we’re in East Harlem and I am with,

Rogers: [00:00:33] Rogers, member of Picture the Homeless for quite a few years.

Lewis: Yes, since about 2006? 2004?

Rogers: [00:00:44] No, going back farther than that. Maybe 2001.

Lewis: Oh, really? Okay! Well, we’re going to get to know you a little bit, Rogers. And then we’ll talk about how you came to be a member of Picture the Homeless. So, can you share with us where you’re from, where you grew up, and some things about your early life that will help us get to know you better?

Rogers: [00:01:16] I suppose a middle-class immigrant experience would probably describe my first fourteen years or so. Born in the Caribbean, came to New York, arrived in New York five days after my eleventh birthday. I guess I was very, very curious at that time and anxious to see what my adult life could be and might be. I was anxious to leave childhood behind. That’s kiddie stuff. So, let’s move on, eh?

Here I am, eleven years old. I was very, very curious about my surroundings. Coming to the U.S. of A., stepping into a Catholic School. Being surrounded for the first time by majority white classmates. That was, that and the church linkage… I suppose my parents’ decision to put me in Catholic School was probably one of the wiser things that they did and that was able to continue the link that I had with Catholicism, having gone to a Catholic School in Trinidad. So, coming into adolescence, and seeing what I had read about and heard about, and meeting people from whom I could learn a great deal, was important to me. I guess I spent the first two years or so just soaking it all in. Everything from seeing what the Empire State Building actually looked like, to finding out what was going on in the heads of some of these—Yankees who were my classmates.

[00:03:17] I suppose one thing that maybe scarred me a couple of ways academically is, maybe even emotionally or socially, was stepping into an environment where I was held back because of my accent, and the presumption that me having an accent meant diminished communication skills, meant diminished intellect. I was forced to repeat the sixth grade coming to the U.S., though I actually should have been going to the seventh, but that was for acculturation. That was for socialization to the American way of life according to the principal and the others who ran the school. So, this would give me a chance to catch up with American customs and culture. When in fact, my first year of school was a repeat of stuff that I had already learned. I really should have been going into the seventh grade. But I suffered through sixth grade, and I endured it.

I was studying them as much as they were studying me, because I was, as I said, curious to see what was going on in American life, in American homes, in American culture. I read voraciously. I probably watched too much television. I was anxious to see movies that I thought would give me a decent view of culture in this part of the world. I was asking questions that many people thought were precocious from an eleven-year-old. Even my friends thought I was acting grown-up and that’s not something that they appreciated. When I would approach them—and, whether it’d be the conversational topic or whether it’d be the questions that I would ask to find out more about who they are and how they got to be who they are—that was not something that they expected of an eleven-year-old, or twelve-year-old or thirteen-year-old as I stepped into my teen years. So, that’s who I was as I stepped on the shores of the U.S. of A.

[00:05:38] It was a learning experience as much outside the classroom as it was inside the classroom. I was sometimes dismayed at how unambitious and unintellectual a lot of my peers and classmates seemed to be. They didn’t want to read. They didn’t want to do homework. They didn’t want to read the classics. And me, I was like, “Okay, let’s find out who this guy Shakespeare is and why he’s so famous.” That was my attitude. Not an attitude that was shared by any of my peers.

[00:06:20] I was more than curious in terms of the religious aspect because I had seen Catholicism in one form in the Caribbean and I was alert to the differences. I was alert to nuances of Catholicism in the U.S. of A., and some of the things that were different. Not the least of which is that, in the United States and in Queens County of New York City—in the mid-sixties—it was a rare thing to see a priest who looked like me. There were not many Black priests in our diocese and our church. It was a rare thing. The few that we did see, more often than not, they would have been people who were visiting from the African seminaries. They came to the U.S. to pursue their studies. That certainly was something I thought was interesting. Nuns, on the other hand, I was probably maybe twenty years old before I met a Black nun here in the United States. That that was commonplace back home, but here it was a rarity. I guess coincidentally, the convent that the nuns have on 119th Street in Harlem, that was… It was of interest to me, what they did, who they were. I had a chance to meet and to talk with the mother superior there at that convent a couple of times and that was, I thought, a wonderful thing.

At one point I’d even thought about handing my daughter over to them, but she would have nothing of it. My daughter thought I was crazy.

Lewis: When you came to New York, what neighborhood did you live in?

Rogers: [00:08:11] I lived in Queens. East Elmhurst, Queens, just on the periphery of LaGuardia Airport. Which was an interesting place, because that portion of New York City had had a Black middle-class community for a great many years. I was maybe a block and a half away from the home of Willie Mays and his gorgeous-looking building. I guess he was one of the earliest Black millionaires who was visible to our community. There were several other people in the community who were people of note. One of my brothers actually went to school with Reverend Butts at Flushing High School and his father, the undertaker of Butts Funeral Home in East Elmhurst, he was somebody that we certainly knew in the community.

I’m just trying to think of the community of East Elmhurst. There were some wonderful people there. I would mention, I suppose, paramount among those was a Mr. Cecil Paris, who was a fascinating character. He was a churchman, an old man, a wise old man. A father of several. As a matter of fact, my first girlfriend, he had adopted. She was biracial, a child who was left in Korea, half-Black, half-Korean. Biracial children in Korea were given all sorts of hell, sometimes literally forced to live on the streets. Mr. Paris, who was very active in our local church and who lived not very far from us, Mr. Paris worked to adopt her and her twin sister, who was severely handicapped, and bring them to the United States.

I mention that because Mr. Paris to me was an exemplary sort. Intelligent, churchman, community man, father. He was the kind of man I yearned to be. I looked up to him in my teen years, Cecil Paris.

Lewis: Am I remembering correctly? Is he related to Anika?

Rogers: [00:10:31] Yes.

Lewis: I remember, okay.

Rogers: [00:10:33] Yes. Yes, yes, yes. His granddaughter would end up working for Picture the Homeless. Yes, yes. Her grandfather was somebody I was greatly impressed by. In my teen years, to me, he was what a man was. I looked up to him and emulated him in his words and actions. His dedication to church, and community, and family certainly appeared exemplary to me. Well, he had a great impact upon me in my teen years. That was East Elmhurst, Queens, not that far from Shea Stadium. That enclave of Black middle class was something that was interesting. I’m sure there are one or two books written about some of the people who’ve come out of that neighborhood who would later claim fame in different ways.

Lewis: Tell me a story about him that kind of exemplifies the way you describe him.

Rogers: [00:11:40] Well, he did not teach in the Catholic School, but he was one of the parents who had the ear of the principal. He would speak to the principal of the school and let them know that there are certain things that it was important that the Black children be included in, because the Catholic school was primary ethnic whites. Germans, Italians, Irish. That was the Catholic school. It was easy for the clergymen, the Christian Brothers of St. John the Baptist de la Salle, it was easy for them often enough to reach out to children who looked like them for different things in the community, whether it be taking them on trips or bringing advantages to them in terms of cultural exposure. It’s everything from getting the children to write their own life stories… And the clergymen, all white who were there in that school, and the nuns, all white who were there in that school, there were times when they seemed ignorant—if not, ignorant and/or oblivious to racism and its impact upon our community and the children whom they were charged with educating.

Mr. Paris, informally more so than within the parent-teacher council, informally they knew that he was a churchman. He would be the one that at times would upbraid them for their ignorance of racial matters, and maybe their neglect of the spiritual growth of the Black children who were in their care and not the least of which is because his children were right there in the class alongside me. He was somebody that they listened to. If Mr. Paris said that such-and-such a thing was not right because they only had white children participating, I am sure that there were conversations that the Christian Brothers, and the nuns, and the priests would then have to deal with. His voice was one that carried some weight. That was just one part of it.

Of course, the other thing is that he made real the faith that we often talked about. Everything from his generous giving to the causes of his own income. He would certainly not be a man who was so stingy when it came to supporting the church. And also of his time, the time that he gave and the effort that he gave to bringing other parents, because a lot of Black parents in that community would send their children off to Catholic Schools for sometimes not so good reasons and you’d never see those parents at the meetings. Mr. Paris would be, of course, in to upbraid them and challenge them when he would see them at the local A&P [The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company] or run into them on the block. He’d be the one to challenge them. And in some ways, he was more missionary than those who wore the Roman collar.

Lewis: In East Elmhurst, did you live in an apartment or a house?

Rogers: [00:14:52] Our apartment was in a private house. We had… Upstairs it was my parents and four sons. There were six of us. So, we were upstairs in a two-family house, which was a comfortable living and it allowed us a very middle-class existence. My parents worked their butts off. My mother went to school, got a degree as a dietician. My father was an optician and between the two of them, they had a decent income. My father, between his habits of drinking and gambling, his considerable income didn’t always make it home on payday. That’s the reality of it. His way of compensating for some of the crap that he had to put up with at work and in other places was sometimes he’d be drinking. That would anesthetize some of the pain of being the second Black employee of Sterling Optical and being a trained and competent professional who was never recognized as such by his employers. He was a boy to them, though he was twice, sometimes three times their age. He was a boy to them.

The man who is now the head of Sterling Optical, the son of the founder of Sterling Optical, was somebody that… My father taught this guy. I remember this guy when he was a pain in the ass and my father taught this guy. This brat would later on be one of the people who scorned the very man who helped educate him in the business. So that was—my father’s dealings with Sterling Optical was—it was a painful thing. Eventually they pushed him out the door, in part because of his drinking, which was caused by the way that they treated him. You know, which is the cause, and which is the effect? He’s drinking because they treated him that way. Then they fired him, because he’s drinking, because they treated him that way. So that was a painful episode he went through with them.

My mother was ambitious. She put herself… Getting through school and getting her degree was very, very important to her. That was part of the reason that my parents actually came to the U.S. before bringing four sons. So, they came here and got their jobs. Then later on, they sent to bring their four sons to New York.

Lewis: Oh, so they came first.

Rogers: [00:17:29] They came first. Got themselves situated, a place to live, a decent job. Then they sent to bring the boys up here.

Lewis: And so, do you think that was part of your excitement to come to the U.S. and see what life was all about here, was to also be joining your parents?

Rogers: [00:17:47] Oh, yes, yes, yes. Because several times between sixty and sixty-five, my mother returned home several times in that interim, so that we missed her. She was living the Yankee life and that certainly seemed to be appealing. Trappings of middle-class life in the US was something that was attractive. Her love for us was in no way diminished by the fact that she had to work, and had to work overseas, and had to go to school overseas in order to accomplish the things that were necessary for her children. My father, similarly, the work that he had to do in order to accumulate the money so that his children could then come to New York, that was part of what we understood. It did not diminish; our closeness was not diminished by distance. They were hard working people, busted their butts so that their children could have a better life and that better life meant, ultimately, their four sons coming to New York.

Lewis: Where did you live in Trinidad when you were a boy before you came here?

Rogers: [00:18:59] I lived in South Quay, Port of Spain, which was—South Quay is—the Quay is literally the wharf. So, it was off of one of the wharfs and loading docks. It was a big train depot. Again, the unloading and shipping of material from the docks to the trains, to the rest of the country, that was something that happened down the block, really, from us.

South Quay was an interesting place. It was again, middle class. Well, it’s funny. Maybe I shouldn’t say middle class but none of us had an idea of us being poor. Even the quote unquote, “poor people” on our block never felt poor or acted poor. So that poverty is not something that was, it was not something that we really recognized, or thought about, or were conscious of in our own families or even the families around us. Because even if so-and-so didn’t have a meal today, you know there’s somebody else on the block who would feed them. If so-and-so didn’t have a job today, somebody else would step in and help them until they were able to get a job or some sort of sustenance. So, none of us would ever have described ourselves as being poor, even those who didn’t have an income. Because in the worst of situations, and I guess this is country living at its best, in the worst situations, you could survive off of whatever was growing in the backyard, or whatever was swimming in the rivers. So that starvation was not something that went along with poverty.

We were educated. And at the time, Trinidad—I think—was second only to Barbados in its literacy. For many years, Trinidad and Barbados had the highest literacy rates in the world. Education was very important to all parents, whether it was the school, government-run schools, or whether it was Catholic-run schools, or other denominations that had their schools. Education was of paramount importance. As I said, the literacy rate among Trinidadians and Barbadians for probably the sixties, seventies, and maybe into the eighties. They alternated being among the highest literacy rates in the world, Trinidad, and Barbados. The inherited British school academic structure may have been responsible in part for that because they ran the schools very much as the schools were run in London. Literacy was something that was critical and required. There was, back at that time, no such thing really as an illiterate adult. It was unheard of. One or another, one place or another, you would have gotten education. Even the country bumpkins had their own ways and systems. Literacy was prized and achieved by almost everyone. Which, I later on found out, was not the, that was not true in all the islands and that certainly was not true throughout a lot of the United States.

Rogers: [00:22:17] That was also part of what, bringing us back to 1965 East Elmhurst, when I would step into a classroom, and I’m surrounded by people, many of whom would not understand the references that I would make, because I had been reading since I was four years old. So, I am making references, and I am saying things that didn’t always come clear to my classmates and sometimes challenge my teachers. Because I was, I guess, confident enough in my abilities, and my family, and my background so that I would challenge them if they talked about illiterate or ignorant West Indians. I would make it a point to challenge them on that.

And that was part of my, I guess, early years. Understanding that I had a higher opinion of myself than the quote unquote, “authorities” around me, which included some of the church people. They did not have a high opinion of me, anyone of my shade, my color, or my background. But I certainly had a high opinion of myself because I knew that I could read. I knew of whence I spoke. I would be able to quote things and people that were familiar to me. It’s everything from understanding the role of Lord Kitchener and the history of England, to maybe even being able to comment on the ethnicity of Cleopatra, the queen, who looked nothing like Elizabeth Taylor. But I was the only voice in the class that would say things like that. Not all the teachers appreciated that because their ideas told them that, again, being from the Caribbean meant, because of my shade and my accent, I was inherently ignorant. I had to challenge that stereotype on almost a daily basis.

Lewis: Even though you - and forgive me if I misrepresent that you said - but you were eleven and looking forward to being an adult. Were there things about Trinidad that you missed when you found yourself in East Elmhurst?

Rogers: [00:24:37] The kinship of family and neighbors. Certainly, the weather, the climate was… [laughs] The harsh weather of New York, that was an ordeal. Maybe some sixty years later, it continues to be an ordeal, the harsh weather of New York. But I certainly missed my family and in later years, much of my family immigrated to the United States and that was significant. I saw the celebrations of my people, my history, my culture. I saw how that was important back home. I was fortunate enough, fortunate would not be the correct word. I was blessed enough that I was able to hold onto some of that here in New York. Finding other people of Caribbean background who would help celebrate our history, our culture, finding the people who were participating in what evolved into the Labor Day Carnival on Eastern Parkway, finding people who were, who saw education as being critical and important.

Rogers: [00:25:53] It is fortuitous that East Elmhurst, where I lived, is also the East Elmhurst that gave birth to the Black Panthers. In that group, there were people who saw and cherished our education and our heritage, which is not something that happened within the school building. Outside of our school, there were people who cherished our heritage and our culture, people who understood and who had read the works of Eric Williams, or Chancellor Williams, or John Henrik Clarke, people who would have understood those things. There were people like that in the community. Some of them would have been part of other churches—not many of them within the Catholic Church, but some of them were part of the other churches, the Baptist Church. Some of the young people would have been part of the Panthers and the work that was being done by the Panthers, critically, to engage young people in a study of our history and heritage, to encourage young people to take pride in the things that did not appear in the typical textbooks. That was a gift from God that I ended up in that fertile ground in that area. That area has birthed some people who were scholars and leaders in many different ways, and I understand how that happened.

Lewis: Could you describe either how you came across those communities or those folks, or something that deeply influenced you about that time?

Rogers: [00:27:40] How I came across those people and those folks? In the neighborhood. I would hear people talking. Down the block from me, actually, there were a set of triplets, one of whom became the director of the Langston Hughes Library in Queens, which some compared to The Schomburg in that it was a place for a study of African culture and heritage. The people who were there, they had the incentive. They had the goal. They had the ambition to pass onto the next generation some of what was critical. That was, that’s just part of what I saw in the neighborhood. I saw people who felt it was important that their children receive an education beyond what took place in the classroom. That was significant to me and that was something that I understood.

As I got into more conversations, and I became more aware of what was happening in the public schools, I began to understand a little bit better the adults who thought that we kind of had to work at educating our children, because the public schools would not do it. That was part of what was going on in the neighborhood in terms of the cultural milieu and the mix—East Elmhurst, Corona—that area extending up to Shea Stadium and Roosevelt Avenue. Within those parameters, there were parents who wanted their children to have more than the public schools could offer. So, their children then ended up in parochial school or ended up getting some sort of cultural addendum on weekends or in the evenings. It could be anything from taking those children to the Pan Yard in Brooklyn to hear the Steelbandsmen play and practice. Because they knew that that was something that was a part of the culture of the Caribbean that was being preserved, in part, by some of the people around Eastern Parkway, around parts of Brooklyn.

Rogers: [00:29:45] There seemed to be more of a cultural heritage, more of a cultural feast happening in Brooklyn. So, a lot of people would travel there on the weekends or the evenings, on holidays, to celebrate that. A lot of the parents would make sure their children had a taste of that, which they couldn’t get in East Elmhurst. “Well, we’re going to Brooklyn. You get a chance to enjoy yourself. You get a chance to be with other people who think, and feel, and are educated like yourself.” That was a significant part of my upbringing, recognizing that in other Caribbean parents in the neighborhood and people like Mr. Paris, who was from, I’m thinking it’s Barbados that he was born because he himself was an immigrant and served in the U.S. Armed Forces. I think he was originally from Barbados. Barbados or Grenada.

Rogers: [00:30:41] Well, he understood the importance of children having a cultural grounding. That was something which was antithetical to what the white Christian clergy saw and felt was a good education. They wanted us to know and to memorize the works of Robert Frost or something like that. We were a little bit more concerned with understanding who the people were of North Africa, and who Haile Selassie was, and why he became famous. That was our priorities contrasted with theirs.

Lewis: And you have three brothers?

Rogers: [00:31:26] Yes, I am the youngest of four sons.

Lewis: Your brothers also… Sounds like you very much relished that education outside the classroom and your brothers also shared that?

Rogers: [00:31:36] For the most part, I will say yes. Because they continued, for the most part, to participate and to work to enjoy their heritage. So, I will say yes. My eldest brother, he went to NYU. Interestingly enough, he was one of the people who founded a steelband at NYU. Other Caribbean students at NYU understood the importance of the steelband in music heritage and culture. He got together with some of the boys that he knew, and some of the girls, and that was one of the things that he had started. That NYU or the university actually had a group, an after-school group that was—it wasn’t a chess team. It wasn’t a football team. It was a bunch of steelbandsmen and that was something that he did with some of his cohorts. And that just represented him relishing our culture and finding a cohort within which he could celebrate that, not just on Labor Day, but certainly at other times to get together with the boys and do what they had to do. That’s part of how within his circle, he was able to celebrate and to carry on the tradition of Caribbean culture.

Lewis: So, your high school days were... Was the Catholic school that you went to also a high school, or did you have to change schools?

Rogers: [00:33:24] I was also in Catholic high school. Again, my parents made decisions. Because it was more their decision than mine, though by that time I had an understanding of why they thought that public schools were not properly serving the youth of our community. So, the church affiliation and the church alliances, that together with the academic ambitions that they had for us is how I ended up attending a Catholic high school, which no longer exists and has since been absorbed by St. John’s University. Now it’s St. John’s Prep.

But that was a Catholic high school and that was an interesting experience, coming from a very Catholic background to people who were American Catholics and seeing some of the distinctions between the Catholic Church as it was manifested in the Caribbean and the Catholic Church as it was manifest in Astoria, Queens. Because up until that time, I guess up until the middle of high school, I had given serious thought to entering the clergy and becoming a priest. My eyes were opened I guess, early in high school, to some of the racism within Holy Mother Church and I gained an understanding of how racism existed within the men who were the leaders of the Catholic Church. Though they would profess that we’re all children of God, there were some serious actions that they would take towards the darker children of God distinct from how they would treat the lighter children of God.

That was part of what I wrestled with in my early teens. Is it possible to be a priest and a racist or a nun and a racist? Sad to say, I was severely awakened to the reality that there were people in the nun’s habit and wearing the Roman collar who were, in fact, racist in their ideals. And many of them didn’t even understand or recognize their own racism. But that was one of the reasons. There were two reasons why I decided not to pursue education going towards becoming a priest. Within the Catholic grammar school, a lot of what they did was intended to recruit children into the priesthood and nunnery—the friary—whatever. But I understood in my early teens that two things were important.

One is that racism was a contradiction within Holy Mother Church. It was very real, and it was pervasive. The other is that the vows of celibacy and abstinence was something I saw as, in some ways, being false and unreal. I was blessed in 19… Oh my Lord, I went to the Eucharistic Congress. I’m trying to think of what year that was. The Eucharistic Congress was held within the United States, it was held in Philadelphia. The Eucharistic Congress being the meeting of the Conclave of Cardinals from the entire world meeting with the local bishops of, well, actually meeting with all who would attend. What happened is that the cardinals and bishops from all over the world met in Philadelphia with the American Cardinals and the American Bishops.

Rogers: [00:37:19] It was a life changing experience for me to be in the audience at that conclave. It was an open meeting that they had, the cardinals and the bishops and there were thousands of us who were in the audience witnessing this meeting. When I heard the African Cardinal stand up and speak out about racism within the Church, I realized, “Hey, I’m not the only one who saw this.” When I heard them speak about how the vows of celibacy are contrary to the laws of nature, that was something that was in my own head. I said, “Oh, the African cardinals are speaking my thoughts.” That was an eye-opening moment. The African cardinals continue to fight with Holy Mother Church, because the idea of celibacy as an unnatural way of life is very much central to the African Catholic Church. That God’s command to be fruitful and go forth and multiply was contradicted by the Catholic teaching that says you prove your love for God by denying your humanity. Hearing that discussion by these learned men, the cardinals of the Church, taking place in Philadelphia, and being witness to that, that was something that, I guess in some ways, was life changing for me.

Rogers: [00:38:39] Because I then began to realize that my thoughts, and my actions, and my words, were not rare. That there were thousands of people who thought and felt as I did and they nevertheless persisted within the Church to make a better Church, which is what we’re all called to—just make the Church a better Church. And the African Cardinals, I understood how they and I were fighting alongside each other to make the Church truly catholic with a small c, inclusive of all cultures and all backgrounds. I understood how they were at times, criticized. How they were at times, ignored. How they were at times, even punished for daring to speak words that were different from what the Pope had spoken.

So, I understood that, and that was a significant moment for me, attending the Eucharistic Congress, the Conclave of Cardinals in Philadelphia. That was just one way, in terms of my own spiritual growth, that was one way that I saw the Church taking us in one direction that was something that I thought was not where God would want us to be. So, the Catholic education allowed me to understand the structure of Holy Mother Church and to understand the rules and the tenets of the Church, particularly as it applied to people of African heritage. Now, that may not have been a direct answer to your question, but that was some of what affected my coming of age. Getting an academic learning, getting a spiritual… Experiencing spiritual growth and at the same time looking for people of like mind and being able to consult with people of like mind, and to read, and to hear, and to learn from people of like mind who at once love God and love our people and our heritage, and saw no contradiction between loving God and loving our heritage.

Lewis: Were you able to have these conversations with your peers? Either in your…

Rogers: [00:40:45] A few.

Lewis: Yes?

Rogers: [00:40:46] A few. Sometimes, this is where, again, people like Cecil Paris were invaluable. Sometimes there were opportunities that he was able to foster and nurture for us to have these discussions with other young men, because he was very concerned that young Black men understand our role through the church. So, we could understand we’re not crazy. That our rejection of celibacy is not a rejection of God. And our rejection of—our deciding not to go into the roles that were seen as the rightful, the typical way of serving God—our rejection of those roles was not a rejection of God. That was something that, by sometimes fostering those conversations, he was able to help us to learn. Even though he may not have been the teacher, he was the one who created the fertile ground within which these ideas could grow, and within which a young man from Trinidad living in New York could end up traveling to Philadelphia and be in the audience of the Conclave of Cardinals. That’s the kind of thing that he did, and he fostered, and it had lifelong effects upon not just me, but certainly others as well.

Lewis: As you became a young adult, what was your life like?

Rogers: [00:42:12] After high school I ended up at NYU. It was a conscious choice for me. Many of my friends went to St. John’s, but I decided after having had twelve-plus years of Catholic education, I did not want to go to a Catholic university. Instead, I wanted to go to what had been fondly referred to by some anti-Semites as NY-Jew. I thought that that milieu, that environment was something that would better educate me than being surrounded by people who were very much like those who surrounded me in church and in high school. So, I ended up at NYU in Greenwich Village, Washington Square, and that was eye opening. That was what college was supposed to be. It put me in the mix. Everything from people who were regular reefer smokers, to people who were homosexual, to people who were ex-prisoners. All of that was in the mix of a college, a university and that’s what, to me, a college, a university is supposed to be. A very, very, varied mix of peoples out of which there’s some resonance of truth in certain ideas. We could learn from each other as well as learn from the academic core. The Institute of Afro-American Affairs, which was headed at the time by Roscoe Brown, that was significant. And that made… They worked hard to make sure that the voices of Black students were heard in different discussions, in different decision-making forums within NYU.

And it was a bigger world. Coming out of the small world of East Elmhurst, Queens, thrown into Greenwich Village into a bigger world with people from all over the world, that was an education the way it was supposed to be. I saw things that forced me to think. I saw things that weren’t familiar. I saw things that made me understand a little bit better my position in the world.

Rogers: [00:44:36] I guess I was probably halfway through, yes, I guess I was probably about halfway through NYU when I first got involved with the Curcia Movement and the Focolari [Movement]. The Curcia Movement and the Focolari were about the empowerment of laypeople to minister to other laypeople in the Church, within the Catholic Church. This happened not at the college, but at the time of college. So, this is what I’d be doing on weekends or whatever during my college years.

It was about understanding that lay people could perform the ministerial functions that are necessary in our community. We could heal and preach, and we could teach each other. The other thing of course, is at that time the Church was coming to grips with a dearth of its recruits. The seminaries were emptying out like mad. Congregants were closing, so the pool from which the Church would ordinarily have drawn its workers was diminishing. And at the same time my understanding and my ability to work with the people who were involved in the Curcia Movement and the Focolari had me understand that the role of lay people was critical. There are things that needed to be done within the church that had to be done by lay people. Certainly, we could no longer count on Sister so-and-so, Father so-and-so, Brother so-and-so doing it. Because there were so few people going into the convents and entering into the different schools that prepared the priests, and the nuns, and the brothers. So, laypeople had to pick up the slack.

And all of this through the late sixties, all of these kinds of things had bubbled up to the point where laypeople were finally recognized as the center of the Catholic Church. Not the clergy, but the laypeople. Laypeople being empowered to do what’s necessary to take the Church forward is part of what I was learning. That was certainly significant in my own growth and development and challenged me in many ways as to what I should be doing with my time and with my life. If I want to serve God, then I have to take it seriously and work to find out where I would be serving God.

Rogers: [00:47:14] And that was, all of that is what I suppose the college years was supposed to be about. As an adult, how do I find my role, my niche, my position in the adult world? That’s what the Church, and the college, and some of my peers helped me to think about. How would I serve, how would I best serve God and serve my community, recognizing that there is no contradiction between the two?

Lewis: This was during the late sixties, seventies?

Rogers: [00:47:48] More the mid-seventies.

Lewis: Mid-seventies? So, what were the other things happening during that time? You had mentioned the Black Panthers. But what was NYU, as a student, what was that area like during this time period? How did that also impact you?

Rogers: [00:48:07] What was the area like? It seems like that area was the, it was the stereotype of pot-smoking hippies. Free sex and pot-smoking hippies is what is the stereotype, and some of that had its verity and that wasn’t always a bad thing. Because if it was the pot smoking that got people to the point that they could communicate and share ideas that might otherwise be buried, then that was a good thing.

Certainly, you had a lot of people for whom coming into adulthood was almost a violent birth. And I know—I knew, and I continue to know enough people, young people—who had severe breaches, severe conflicts within their families, that in order to birth them as an adult, their parents had to go through. I knew enough young people whose parents cut them off, cussed them out, threw them out of the house for doing what was probably normal and natural. Again, whether it be gay, or smoking pot, or hanging out with people of color. I knew enough young white folks, who were predominant at NYU, and certainly, I don’t know if the stereotype is true. But the stereotype was that most of them were Jewish. I don’t think that necessarily was true. At the graduate level, I think it might have been true but not the undergraduate level.

But I knew enough of them who were ostracized, who were penalized, criticized for participating in liberal ideas so distant from their own parents’ mores. To have a Black person spend the night at their house or to spend the night at a Black person’s house, I had many friends who, they went through hell with their parents for that reason. Their parents couldn’t understand. “What’s this colored boy doing here?” And conversely, “You’re going to go spend the night in the ghetto? What are you doing hanging out with those people?” A whole lot of my white friends, that was almost daily. “What are you doing hanging around with those people?”

So that for some of them, that was something that was traumatic, eye-opening. I could think of several people who were brought to tears at the recognition of their parents’ attitudes that were so contrary to the liberal thinking which we as undergraduates shared. When they found out that their parents had been funding groups like the Klan, when they found out that their parents’ Unions would not allow people of color to join, when they found out that their parents’ neighborhoods would not allow people of color to move in, this was traumatic for some of my classmates. When I would say certain things to them, they would look askance at me. And a week or a month or two later, they’d come back, and they’d say, “Oh my God. You were right.” They would have their eyes opened to realities that were the norm to me. That was part of what college days were. I saw some of how they lived. And they saw, some of them saw some of how I lived and understood some of the realities that were part of life for people of color here in New York.

And some of the stuff that I would have told them about my everyday life, six months later they’d say, “Oh my God, you were telling the truth.” Some of the things that went on in their lives or their families’ lives, again, like funding groups like the Klan or prohibiting Black employees, “We’ll only hire that colored boy if he’ll work as a maintenance man.” This was kind of the thing that some of my white friends couldn’t believe they were hearing their parents say and I was telling them, “This is what I’m telling you about.”

That’s some of what my college years… Put that together with my working within the Church, within the Curcia and the Focolari Movement, working to bring young people closer to God. And all of this tumult is, I guess, me in my twenties, searching for what it is that God calls me to do and ever wanting to be a servant of God and not being clear how to best fulfill that challenge.

Lewis: What do you think it is that God calls you to do?

Rogers: [00:53:05] I don’t know. Would you believe me if I say to sit down and talk to a tape recorder about what the last sixty years was like? That’s a small point of what God calls me to do. To be real and honest to the people I deal with. To be clear as to my motives for acting. To challenge Satan in his many guises. To ultimately—simplistic theology—we come from God and our goal is to get back to God. So, to get closer to God, there are things that we have to move out of the way. Those things can be mercenary. Those things can be sensual. Those things can be political. We have to move certain things out of the way to get closer to God. The God that gave me life is the God that commands that I return.

If I live my life right I will, upon my death, return to the God who gave me life. If I live my life right. In the interim, I am challenged to recognize and move obstacles out of the way. That’s simplistic theology. That’s some of what has been guiding me certainly for the last forty years. And if I am honest, and open-minded, and open-hearted I will be able to recognize the things that bring me closer to God and adhere to those things. And similarly, to recognize the things that distance me from God and find my way to be rid of those things, to conquer those things. The Seven Deadly Sins, ostensibly they are the things that separate us from God. Can we recognize and conquer them? How much does money and profit and physical wealth, how much does that get in the way of being closer to God? I mean, these are the things that for the last forty years I’ve been wrestling with. And the challenge is always there, that if I do things that are right, I will be closer to the God who gave me life. and upon my death, I would have achieved my mission of returning to the God who gave me life.

Again, simplistic theology. But it’s some of what I have worked on, worked with, for the last forty years.

Lewis: Some of the last forty years you’ve been a leader at Picture the Homeless and I also know you’ve been involved with a lot of other types of community work. Tell me about when you first learned of Picture the Homeless? How did that happen?

Rogers: [00:56:13] When did I first learn of Picture the Homeless? My Lord. It was before I became homeless. The first time I heard of Picture the Homeless… I have a feeling that it was probably some clergyman or woman who would have mentioned that to me, that there are church people who are working to combat homelessness in New York City. I suppose I’m just thinking of where I would have been working. I was involved in low-level community politics, block associations and things of that sort, through the nineties and some of those low-level politics certainly in and around Harlem, would have introduced me to some of the people of Picture the Homeless. I attended lots of different church-based rallies, meetings, forums in that period, in the late nineties, early 2000s. I attended many different meetings of groups who worked ostensibly to help the community and some one of those meetings would first have brought Picture the Homeless to my attention.

I moved to Harlem in—I guess it was probably around 1990 I suppose—I moved to Harlem. I attended lots of community meetings, lots of civic association meetings.

Lewis: What was Harlem like then at that time?

Rogers: [00:58:27] Harlem was beginning to divide into enclaves. People who were political and poor. People who were political and of modest means or of some wealth. People who were Black Caribbean. Certainly, the Young Lords. I’m trying to think of what years they would have been most active in Harlem. I’m guessing that probably would have been the seventies and eighties. So, by the nineties they certainly… El Barrio had come into some repute as a political melting pot. Living in Harlem, it was inevitable that sometimes at different meetings I would be dealing with people who were Latino, Asian, or white, who were left—left-wing radicals is the label that would be laid upon them, or us. After having attended a few of their meetings, I began to realize that as Pogo in the comic strip would say, “Them is we is us.” I began to understand that the left-wing radicals maybe, maybe, maybe was part of what I had evolved into. A left-wing radical.

Rogers: [01:00:02] Because of my education, because of my church work, and my church work is something else that became important. Running retreats for young people, college age young people, and coming toe-to-to with some other folks, I was very active in the formation of a group that became known as the Council of Black Catholics. The leader at the time, well our elected leader, was Laura Blackburn. She was an interesting woman. A Catholic woman who had been appointed by Mayor Dinkins to be… I think she was second-in-command at the Board of Education. No, the Housing Authority. She had been appointed as the interim head of the Housing Authority and I had known her, done some church work with her. I knew her to be a woman of sparkling reputation. A fantastic woman, and a woman I admired in so, so many ways.

One peculiar footnote [smiles] is that she would once or again come by my house and stop by, because I was the guy who would videotape Star Trek on Thursday nights, because we had meetings. So, she knew that we were at the meeting on Thursdays, but she could come to my house on Saturday and watch the videotape of Star Trek. Such an oddity. [Laughs] But Laura Blackburn and I, we’d done some work. And again, the things that the Church and Holy Mother Church commands of us were being denigrated as radical left-wing and ostensibly this is the label that they slapped upon us. And we said, “This is who we are. This is what we do. You call us what you want, but this is who we are, and this is what we do.” We didn’t call ourselves left-wing radicals.

Lewis: What are some of those things?

Rogers: [01:02:02] Fighting for integration and fair housing laws. Fighting that our children could have meals in the schools if they did not have meals at home. Fighting so that… There are women who were victimized and that the cost of healing, housing some of the women who were victimized be borne in some part by the state—which sometimes was the employer of those who had victimized the women—and these were radical ideas. We were left-wing radicals. That is the label that they slapped on us. It was saying that a woman with three children who had just been battered by her husband for the thousandth time, and crawled out the door and said, “I’m not going back to him”, that someone should work to provide her a place to live. We were left-wing radicals for saying, “Do you know what? Maybe we should be providing her a place to live, because the fact that her husband’s an idiot and a brutal person is not something she should be punished for.” But politically, some of these were radical ideas that we were speaking thirty years ago.

Rogers: [01:03:12] And… So that was—but this is consistent with the church upbringing and doing the work that God commands us to do—that both she and I shared. Because she is a churchwoman, and she continues to this day to be a churchwoman. The commands of God is what we were adhering to. The fact that that put us face-to-face with some gun-toting police officers, or would land us in handcuffs, that is who we were. That is what we were commanded to do. And the woman had more balls than most of the men I know and that is who she was. So, she was active. She was one of the leaders of the group, the Council of Black Catholics, and she was also politically active. She and her husband because I should not diminish his role. Because I am sure that that was a challenge to him and to them when people saw that kind of a marriage. Laura and Hank Blackburn in Southeast Queens, they did some wonderful things that helped advance the cause of fairness, justice. I don’t think either one of them have ever gotten the recognition that they deserve, or that they’ve earned.

I mention them, because the coming together of church and politics is exemplified by some of the things that we were doing. There were instances where you had people of color who were being denied jobs. Certainly, within the police department, which is something else that I became very much aware of working within the police department. There are instances where you had housing that was being denied from people because of their color. And we were commanded by God to do something. We can’t just sit still, and say nothing, and do nothing. We’re commanded to do something in the face of this injustice.

Rogers: [01:05:16] And that is some of what I guess eventually became important, became more and more important to me. So that the middle-class lifestyle of a staff analyst within NYPD was something that did not quite seem to be the peak of the mountain that I wanted to climb and there are some questions and some choices that I had to make. I had to recognize, if I’m serious about serving God, there are things that I have to do that are going to be unpopular, that are going to be criticized, condemned by some other folks, and recognizing that is some of what I guess the seventies and eighties brought me to. That if I were to obey the commands of God, that meant that now and again I had to disobey the commands of, quote unquote, “lawful authorities.”

Rogers: [01:06:29] And that was, all of that coming together with my own spiritual growth and political, as my eyes became opened politically, all of that is what led me to the point where I had to, where I was attending meetings with more and more people who were involved in social justice and I felt commanded to support them, because I realized they were not the left-wing radical lunatics that some of the media made them to be, present company included. It is important to me that A, they know that I support them, and B, that other people know that they’re—these are not a bunch of crazy lunatics. The people who would fight for justice. The people who would fight for housing. The people who would fight to aid those who needed help. That, you know, it’s not crazy lunatics who are doing this.

Rogers: [01:07:30] And that evolution, that growth throughout the eighties and nineties is part of what would have pushed me eventually to attend neighborhood meetings, one of which I’m sure would have been Picture the Homeless, even before I became homeless. Because my political conscience was awakened. That’s part of what led to the... The awakening of my consciousness would have led me to some meeting that Picture the Homeless would have convened in Harlem. And at the time there were people in Harlem, like myself, who felt compelled to act, to speak. Some of those people were in conflict with the new Harlemites who were buying in and moving in. The new Harlemites, people with money, mostly white, for some of whom, profit and exploitation were foremost among their priorities.

That was, all of that is what was going on in—I guess—going up to the nineties and recognizing who the people were who were at odds with what I felt was the commandments of God. It is important to me to understand that if I work to serve God, and others work with me to serve God, that we’re on the same side. That means that sometimes the assault on them, if they are being arrested, they’re being assaulted, they’re being attacked, they’re being vilified, then I may have to face the same assault and vilification. That’s part of what I’m commanded to do—not be a bystander, but to participate in the fight, ultimately, for justice.

Rogers: [01:09:44] And_ _I am awakened to that in the late nineties. At the same time ultimately, a whole lot of other circumstances led to me being homeless. And the group that I felt was fighting for justice, speaking for and on behalf of the homeless, and doing the things that I saw or heard as God’s commands, that was the Picture the Homeless people! And that’s, you know, it’s like, “Okay, if these people are doing the same thing that I’m doing, then maybe I should be doing it with them, as opposed to being a lone wolf someplace.”

Lewis: When you became homeless, did you go find Picture the Homeless? Or did Picture the Homeless find you?

Rogers: [01:10:38] I had attended, as I said, several meetings probably convened by Picture the Homeless, or at which people from Picture the Homeless had spoken. I had attended several of their meetings before I became homeless. At the time that I became homeless, I was recognizing that there are people who are working with Picture the Homeless who were in the same shelter or in the same situation and that affinity just brought me more regularly into contact with Picture the Homeless, when I realized that some of these people are talking about the same thing I’m talking about. And they’re working for the same things I’m working for on behalf of a group, not just on behalf of themselves.

[01:11:24] And it is common, I suppose, or it was common, a lot of people who were homeless, who were in the shelters, they’re concerns were just for me, myself, and I. That self-centeredness sometimes is born of a fight for survival. But at the same time, there are people who are fighting the fight for housing for all, not just housing for me. And that coming together of my political and religious beliefs is part of what said to me, “If they’re fighting for homeless, on behalf of the homeless people, to get homes for everybody, then that’s something that I should support more than just fighting for myself to get a place to live.”

Rogers: [01:12:07] So somewhere in the shelter, because that’s where I would have had my contact with, or the largest amount of contact with people who are homeless, somewhere in the shelter there was an echo or a reverberation in my mind of what I had heard prior to being in the shelter. That this group is fighting for everybody who’s homeless, not just fighting for themselves.

Lewis: Mm-hmmm.

Rogers: And from there, I was seeking to find out when and where the meetings were and when and where were the opportunities for me to do some work with Picture the Homeless.

Lewis: Was it challenging? How did you find out where the meetings were and when they were held?

Rogers: [01:12:47] Now, I’m sure that the office for PTH would have been 116th Street at the time. Maybe it would have been before. When… Do you know what date they first moved into 116th Street?

Lewis: I believe we moved to 116 in 2003.

Rogers: [01:13:07] So then, even before that office was open, there would have been some of the people from Picture the Homeless that I would have spoken with. Because when I was in the shelter, I think it would have been 2000, 2001. When I was in the shelter, there were several people who would mention to me Picture the Homeless and I’m wondering if I would have run into Anthony Williams in the shelter.

Lewis: What shelter was it?

Rogers: [01:13:36] One that no longer even exists in upstate New York.

Lewis: Oh, Camp LaGuardia.

Rogers: Camp LaGuardia. Camp LaGuardia. That and Bellevue. Because I was at Bellevue for, I don’t know, maybe two weeks before they sent us up to Camp LaGuardia. So, it might have been at Bellevue that I would have first heard about the meetings of Picture the Homeless. Because I realize now it would have predated the office on 116th Street.

Lewis: [01:14:04] So, Anthony and Lewis were in Bellevue in the fall of ninety-nine and then into 2000. And then were both given—well, Lewis was given a twenty-four-hour notice of being transferred to Camp LaGuardia—and Anthony just had security tell him, “You’re going up there”, in retaliation for organizing. But Picture the Homeless was having meetings, attending meetings in Harlem, at the National Action Network, at Harlem Tenants Council, and in St. Mary’s Church.

Rogers: Nellie Bailey.

Lewis: Yes.

Rogers: [01:14:41] All three of which sites—St. Mary’s Church, the Tenants Council, National Action Network, all of those sites are places where I would have attended meetings at that time. So, I may have met them or you, there. I realize now it was before the offices opened on 116th Street because I lived three blocks away from St. Mary’s. I had done some work with Nellie Bailey and the Tenants Council and certainly the National Action Network. When did I start attending some of their meetings? Oh boy. National… It probably would have been the late nineties I would have started attending their meetings. So, one of those three places or maybe all three of those, because if it was concurrent, if I heard it once, and twice, and thrice, maybe the message finally sunk in after having heard it three times.

Lewis: Yeah, Harlem Tenants Council had an office on 125th Street, I believe. In my mind I’m picturing it being upstairs. It was a…

Rogers: With Jim Horton. Fifth Avenue off 125th Street.

Lewis: Where Applebee’s was, right?

Rogers: The building behind it.

Lewis: [01:15:54] Mm-hmmm… So, there were meetings, there was an anti-gentrification march. The market on 125th Street when that was closed...

Rogers: And the vendors.

Lewis: Anthony was involved with quite a few of those and also on the Lower East Side. There was a lot going on in both places.

Rogers: [01:16:17] It may well have been through Jim Horton, rest in peace. Yes, one of those three places I would have first heard of Picture the Homeless. Then, to have been invited to their next meeting and the next, which I can’t even think of where it was because now it was before 116th Street. So, if I was invited to a meeting at Picture the Homeless, I don’t know where that would have been. Eventually it’ll come to me.

Lewis: So, when you became homeless, and you first went to Picture the Homeless…

Rogers: [01:16:53] Well, Camp LaGuardia, 116th Street was not yet open when I was at Camp LaGuardia.

Lewis: So, talk to me about when you, as someone who was homeless, when you first went to Picture the Homeless. What were your impressions?