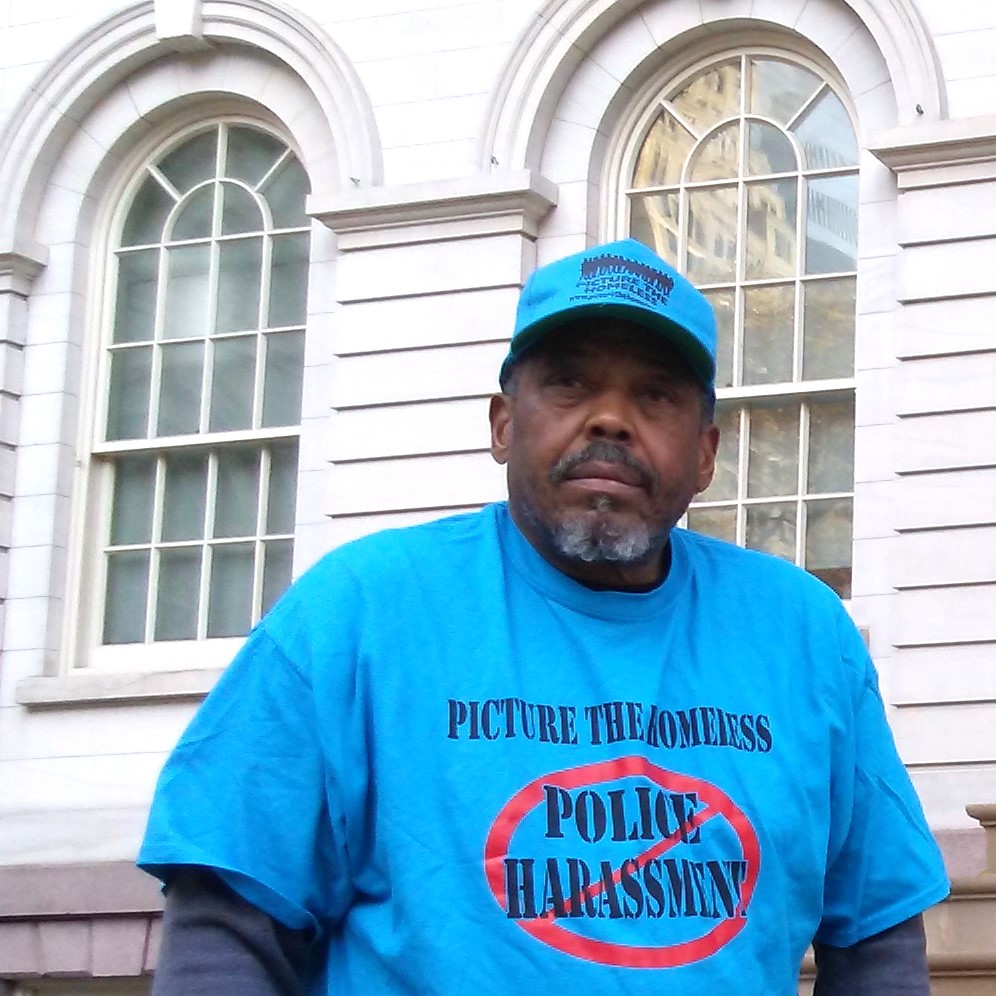

Floyd Parks

The interview was conducted by Lynn Lewis with Floyd Parks, in the office of Picture the Homeless (PTH) on October 25, 2019, for the Picture the Homeless Oral History Project. Floyd joined PTH in 2015 and was an active member of the civil rights committee until COVID hit in 2020. This interview covers his early life, experiences with the NYPD, meeting PTH and his reflections on organizing and movement building.

Floyd was born in Elizabeth, New Jersey and raised in Roselle, a small, racially diverse town. Growing up in the ‘60s there were racial tensions and violence. “It’s a situation where you learned how to communicate with people. Instead of showing anger and fear, you learned how to talk.” (Parks, pp. 3) The youngest of four, he lost his mother at age sixteen and began drinking

and getting into bar fights.

Later, Floyd worked as an EMT on Long Island, were he was married and had two step-children. “I did that for about a good two years. It kept me straight, kept me sober, kept my mind focused. It gave me a sense of achieving, you know, made me feel good doing something, something that meanwhile is helping somebody else” (Parks, pp. 5) He and his wife met in a substance abuse treatment program and were happy for a time but both relapsed and he returned to Harlem, where he had been living previously, “ever since then, I’ve been homeless, in and out of programs and shelters and rehabs, just to try to keep myself off the street, try to stay healthy, and try to keep some kind of focus, not let it get to me too much that I’m—penniless, homeless, ain’t got nowhere to go, sleep, you know what I’m saying? I really got tired of the curb, so I used to go into rehabs and programs, stay in six months, ten months, because I figured I needed that because I was really feeling… Suicidal.” (Parks, pp. 6) He credits PTH with giving him a way to understand and communicate his feeling and to be a person that is “heard and, you know, worth listening to. It’s a good feeling.” (Parks, pp. 6)

Graduating from high school in ’74, he left home and came to NYC and began hanging out and drinking and got caught up in drinking every day. Reflecting on the political context in the ‘70s, he connects Nixon’s abuse of power during Watergate to abusive policing. “That’s how I looked at cops for a long time because they had the power, they had the right, they had the gun—to just come up to me and tell me anything, and whatever I got to do, I got to do it. If not, they’re going to use some kind of restraint, force on me, so—you know. That’s abuse of power, as far as I’m concerned.” (Parks, pp. 8) And he shares times when he walked away without saying anything as well as times when he spoke up, and other folks appreciated him for that.

This interview was conducted just after four homeless folks were murdered in NYC’s Chinatown and Floyd shares being street homeless in Chinatown in 2014 and was beaten so badly that he had to be hospitalized. Floyd describes adjusting to street homelessness, and having to throw away his pride to ask for money, “all of a sudden you’re in this situation that, wow, I’m somewhere I never said I’ll be. I’m here, and I’m begging. I’m asking people for money. I ain’t took a shower in three or four days, you know.” (Parks, pp. 9) He wants people to understand that homeless folks are in need, and that it’s not easy surviving on the streets. “Living in the streets is mind-boggling sometimes, the things you’ve got to deal with, the people walking over you, around you. You don’t know who to trust, who’s going to hurt you, who’s going to do something to you, because it could happen just like that. Somebody could just do something to you because you’re just laying out there, vulnerable, in the middle of the streets. That’s why it’s dangerous.” (Parks, pp. 9)

Finding community with other homeless folks under the MetroNorth train tracks on 125th Street in Harlem, people shared and helped one another out. “There are some good people out there that fell into the hard times and all of a sudden they’re in the street, but they got a good heart, got a good soul, but they’re homeless, you know?” (Parks, pp. 10) The police would tell them to leave but they had nowhere to go. They would be harassed from place to place like cattle, threatened with arrest or being taken to the hospital. “It’s bad enough being homeless in the streets. Then you get harassed by the cops every day. You can’t sit down. You can’t rest. Oh, you got to move here. You can’t stay there.” (Parks, pp. 10) And he again emphasizes the need to communicate, and to let somebody know what is happening.

Meeting Nikita Price, PTH civil rights organizer, Floyd started talking with him and then speaking in public. He shares the importance of people seeing that something good is being accomplished and encouraging other homeless folks to come to PTH. “Oh, man! I seen you on TV the other day. Man, I like what you said…” I said, “Wow, what you… Are you going to help out or what? Are you going to join in?” He said, “Yes, no doubt. How do I do that?” “Go around the corner to 126th Street—Picture the Homeless.” (Parks, pp. 12) And he shares how working with PTH made him feel good because he was helping someone else. At first he didn’t believe PTH could do anything for him until he got to know people there. The NYPD retaliated against him after he started speaking out. Attending a meeting of the Inspector General of the NYPD he shares his thoughts. “That was a meeting to make them look like they’re going to do something, make them look like there’s a possibility that they’re going to listen to us. Therefore, they’re—putting on a show, to me—just to make themselves look good, that they had us there, that they attempted to talk to us. They were saying nothing but, “We’re going to do this, we’re going to do that, we’re gonna, gonna, gonna, gonna, gonna…” Ain’t nothing being seen, and nothing— We said, “Well, you said this—a year ago and there’s nothing being done! You’re just—all you’re doing is blowing smoke up our asses.” You know? That’s what the kind of meeting was to me.” (Parks, pp. 14) But still feels it was important to be seen and to express the seriousness of the reform that needs to happen.

Floyd describes an incident where the NYPD and Department of Sanitation work him and other homeless folks up and threw their property away, including ID’s and medicine. PTH and NYCLU worked with him to file a lawsuit, and his thought process leading up to that. “I’ve got to continue on! I’ve got to make this mission known. They just can’t keep doing this stuff, and people just turning their back, letting them do it. If they see it, they don’t say nothing. I mean, it’s got to stop. The way that we’re being treated out there, the way we’re being put in situations as—you know, in harm’s way. That’s got to stop.” (Parks, pp. 15) They were awarded damages for lost property, and he was glad that it’s documented. He encourages others to stand up and be heard, and describes what PTH means to him. “It means hope. It means achievement. I have achieved something since I’ve been here that I probably wouldn’t have, you know. I’ve got a place to lay my head. I see a little more of my pride and my dignity and my self-respect coming back, because I’m not doing these crazy things that I had to, to survive in the streets.” (Parks, pp. 23) And he shares the importance of being listened to and PTH taking action.

PTH Organizing Methodology

Being Welcoming

Representation

Education

Leadership

Resistance Relationships

Collective Resistance

Justice

External Context

Individual Resistance

Race

The System

Prejudice

Communication

Understanding

Respect

Detox

Recovery

Change

Abuse

Power

Cops

NYPD

Street

Rights

Retaliation

Danger

Survival

Village

Metro North

Help

Fun

Housing

Elizabeth, New Jersey

Roselle, New Jersey

Long Island, New York

New York City boroughs and neighborhoods:

East Harlem, Manhattan

Chinatown, Manhattan

Harlem, Manhattan

Civil Rights

Homeless Organizing Academy

Movement Building

Organizational Development

[00:00:00] Introductions

[00:00:39] Born in Elizabeth New Jersey, raised in Roselle New Jersey, a mixture of everybody, Black, white, Spanish.

[00:01:02] Born in the fifties, raised in the sixties, a lot of tension and prejudice, KKK marches, Martin Luther King, things were rough, importance of communication instead of showing anger and fear, you learned how to talk. It’s important to him to show care and concern. There’s a better way of doing things.

[00:02:53] During a time of racial tensions, at age twelve or thirteen he had already earned some respect from white youth in the area, saving him from potential violence right before a race riot broke out.

[00:04:37] It wasn’t really the KKK, but people’s opinions who were still living back in slavery days, their minds hadn’t adjusted to a new time and day, he tries to avoid people and situations like that.

[00:05:39] In his sixties, he has experienced things that have given him nightmares and other things that have given him joy, he’s learned how to talk and to cope. You’re not living if you don’t learn something new.

[00:06:21] The youngest of four children, two of his siblings have passed away, it was hard to take.

[00:07:05] At age sixteen his mother passed away, which sent him off on a crazy binge, started drinking, doing crazy stuff, was a menace to society.

[00:08:03] Later, worked as an EMT for two years, it gave him a lot of joy taking care of people, lived on Long Island, it was peaceful, kept him sober and his mind focused and with a sense of achievement.

[00:09:11] Family life on Long Island, stepchildren, met his wife in a drug program, both were in recovery, they got married and everything was beautiful for a year or so, wife relapsed, then he did, then they were suddenly trying to kill one another, and he left.

[00:10:23] Came back to Harlem and has been homeless ever since, in and out of programs, shelters and rehabs, trying to staff off the street. Penniless and homeless, was suicidal, really depressed. Thanks God for people like Picture the Homeless where he can communicate and understand his feelings, talk, and express himself and be a person that can be heard and worth listening to.

[00:12:26] Graduated high school in 1974 and left home. Came to New York, met people hanging out drinking, bought drinks to share, started drinking every day, it became a lifestyle.

[00:13:59] Felt himself slipping down, had seen other people let the streets get to them badly, losing all hope and desire to live. He knows that feeling, he’s been there.

[00:14:40] You have to make the change; nothing comes to you. A closed mouth never gets fed, you have to learn to speak up, you have two wolves inside of you, a good one and a bad one, the more powerful one is the one that gets fed.

[00:16:32] During the seventies and eighties the political landscape, Nixon and Watergate, people abusing power taught him that people with power can have the right to violate people, cops have power, rights, guns for example, he learned how to walk away, there’s a time and a place to speak your mind.

[00:18:29] When he’s spoken up, people have said that he made a lot of sense, he’s trying to let people know what’s happening, four homeless people sleeping outside were murdered in Chinatown, he was beat up in the same area in 2014, stomped on, hospitalized, and needed surgery.

[00:19:59] Experiences being homeless out on the street, he had to adjust to a lot of things, you don’t know where your next meal is coming from, there’s no more pride, asking people for money, you lower yourself to somewhere you said you’d never be.

[00:21:54] Advice to homeless folks on how to communicate when asking for money in the street.

[00:22:32] What he wants people who aren’t homeless to understand, people have needs and don’t mean harm, some are serious about getting something to eat, some are trying to get money for a drink that they probably do need badly to get through the day.

[00:22:54] Surviving the streets isn’t easy, sometimes drinking and drugs help you cope, people walk over you, around you, you don’t know who to trust, it’s dangerous.

[00:23:30] He met other homeless folks and formed community near the Metro-North station on 125th St. for six, seven years. People had nowhere to go, or sleep, cops were waking people up, they came to be like a village, helping one another. You had to find people you could trust, some people have fallen on hard times and become homeless but have a good heart, a good soul.

[00:25:23] Interactions with the police, cops told them they had to go, but they had nowhere to go, cops said they didn’t care, just to leave the area.

[00:26:01] They were probably getting complaints from the community, cops tell them to scatter out, and separate, move them around like cattle, it’s frustrating, police threaten them with arrest or going to the hospital. He just gets up and goes.

[00:26:49] It’s rough, wouldn’t wish it on his worst enemy, bad enough being homeless but then harassed by the cops, can’t sit, can’t rest. It makes you angry, there’s got to be a better way and the only way is to let somebody know how it is.

[00:28:11] Fist heard about Picture the Homeless while staying under the Metro-North, Nikita Price approached them, offered assistance, and wanted to listen to their problems, told him he liked the way that he spoke, invited him to speak in different places, learned how to communicate what people were really going through.

[00:29:12] He began talking information back out to others in the street, one person who got involved that surprised him was Country who said he didn’t need help, but he saw that the things he wanted to do, he couldn’t do on his own and the organization could open doors, people advocate and speak up for you.

[00:31:48] Participated in press conferences, sleep-outs, the impact it had by putting it in the face of people who don’t involve themselves, something they’ve got to see, they have to listen, make it interesting, understandable.

[00:32:42] Ways that Picture the Homeless made things understandable, communications, interviews, conversations, let people know something good is happening, people saw him on TV, he’d ask them to join Picture the Homeless, spreading the word.

[00:33:51] The experience becoming part of Picture the Homeless and encouraging others to join was a good feeling, helping someone help themselves helped him, his first impressions of the office were that they couldn’t do anything for him, they were just trying to get money but then he saw how truthful they were, and it was something he saw the need for.

[00:34:54] Interviewers first impressions for Floyd were that he was powerful, speaking out against the 25th Precinct and the police while still out in the street. One time a cop addressed him by name, gave him a ticket for jaywalking but it was thrown out, he was singled out and that showed him that he needed to watch it.

[00:36:01] Participation in a delegation that met with the Inspector General of the NYPD, the meeting was to make them look like they were going to do something, it was a show to make themselves look good, they were blowing smoke up our asses. These meetings are still important to do, to be there, to let them know that something needs to change.

[00:38:19] He and other homeless people had been sleeping by a school. There’s a video of him and others awakened by police kicking their feet, flashlights in their faces, they were told to leave the area and their belongings were thrown into the garbage, on October 2, 2015.

[00:39:31] He was talking with Picture the Homeless and lawyers from the Civil Liberties Union, Alexis Karteron got the video footage that showed exactly what happened, they couldn’t lie.

[00:40:14] Belongings that were in his cart that were thrown away, clothes, documents, social security card, wallet, jewelry, medication, vitamins. He and two other people filed a complaint.

[00:41:02] He had to understand the decisions that had to be made, and to decide to go along with it, worrying about cops messing with him. He decided to continue, it’s got to stop.

[00:42:14] They had moved to sleep at the school because the police told them to leave the Metro-North area and sleep by the school, on 127th St. Neighbors didn’t bother them, and the security lady would wake them at six in the morning, they would clean up so that they could come back, other folks staying there included Chyna, Doc, Triple R, Country, Rick, and Nene.

[00:44:01] The complaint was filed with the Comptroller’s office, he wanted an apology, the lawsuits proved the police were wrong, documenting it made it a little better, showing what they were doing, the three men received compensation for what was lost, in the amount of $1,515, nothing for pain and suffering. It wasn’t enough, but it was uplifting to go upstairs to his office and physically file it, in the winter of 2016 while he was still street homeless.

[00:46:06] In May of 2016, filed a complaint with the Human Rights Commission with the same lawyer about the NYPD profiling homeless people. Even if we don’t win everything we should, it’s still important to speak up, he tells people who don’t believe things will change that you have to stand up and be heard, or else it won’t happen.

[00:47:01] How this has changed his life, his self-esteem was shot, he can do something worthwhile and help others to accomplish something. He still has a relationship with Nikita, the Picture the Homeless organizer, he feels he’s achieving something.

[00:48:02] Although he now has a place to live he still visits his friends that are still in the street, cops ask him why he’s there because he has a place to live, cops know who he is, and know he’s someone to be reckoned with, he has a little clout to help him be listened to.

[00:49:15] “Move on” orders became official NYPD policy toward homeless people, the impact on him and others, it’s very aggravating because you’re not breaking a law, they say you’re an eyesore, they don’t want to see us, move us here and move us there.

[00:50:31] Police come in vans, and take milkcrate saying they’re stolen property, put them in the police car, or thrown them over the wall, they wear gloves, and the gloves mean the police are too good to touch them, as if they have a disease. The police tell them they’re getting complaints and orders from higher ups.

[00:53:05] Solutions to homelessness and what would have helped him is the help he gets now, organizations that can guide you. The help is there but not out in the open. You’ve got to be connected to an organization that can refer you.

[00:54:24] Relationship with Nikita and what it meant that Nikita spent the night with him in the office so they could attend a meeting, it showed his seriousness, that it meant something to Nikita, it made him feel good.

[00:55:16] The cookout that he and others did in the office, what it meant to use the kitchen, fun times at Picture the Homeless with food and dance parties.

[00:56:77] Stays involved with Picture the Homeless because it gives him something to occupy his mind, something positive, he’s achieving something, benefitting himself and others, something positive can be accomplished out of all this misery.

[00:57:08] What the City needs to do to end homelessness is have more places with counsellors and doctors, some people have serious mental problems, others are comfortable where they are, it bothers him a lot. He still visits his friends from the village, checking on people because it’s rough out there.

[01:00:24] Picture the Homeless means hope, it means achievement. He’s gotten a place to lay his head and more of his pride and dignity and self-respect because he’s not doing the things he had to do to survive. He’s had to adjust to being homeless and now to having something again.

[01:01:47] Picture the Homeless provided two things, help with getting services and fighting for people’s rights. Both were important because you know someone is listening and seeing the seriousness of what you’re saying, you’re able to express yourself and be heard.

[01:03:33] Some groups do one of those things but not both. If Picture the Homeless provided services but didn’t fight for rights and dignity, that would be different because they wouldn’t be looking at what needed to be done, they’d just be trying to look good and not accomplishing what somebody needs done, they’d just be a storefront.

[01:05:24] His perspective as a leader with Picture the Homeless can help teach others. Everything Picture the Homeless tried to achieve was accomplished or is pending. Everything that was planned was organized and done professionally, done with the backing of the people that needed and wanted it to happen.

[01:06:45] Advice to other homeless folks who want to organize. People have to get together, take leadership, people need housing and there has to be a plan, knowing where to start and what they want to achieve, someone has to know how to go about this and believe in what was happening, and not just listen but take action and make things happen.

[01:08:30] Memories of actions, they were all uplifting, every time he spoke, he got something out of it, it was challenging and rewarding and helpful, he participated in looking at what was going on, discussing, seeing what needed to change, talking, everyone comes to an agreement and try to go from there.

[01:09:47] Things that contributed to an environment where people agreed about what needed to be done, they saw the seriousness of the topic and what they were doing, they believed in what they were saying and felt it was the right things to do.

Lewis: [00:00:00] Yes, Okay. Good morning.

Parks: Good morning, how you doing?

Lewis: I’m wonderful. I’m happy to see you. My name is Lynn Lewis, and I am interviewing Floyd—

Parks: Floyd Parks.

Lewis: —Floyd Parks, Civil Rights leader—

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: —at Picture the Homeless.

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: We’re in the Picture the Homeless office, and it’s October 25th, 2019.

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: Hi, Floyd.

Parks: How you doing?

Lewis: I’m great. We are going to get to know you a little bit before we talk about your work with Picture the Homeless. So, could you share where you’re from?

Parks: [00:00:39] I’m originally from New Jersey. I was born in Elizabeth, New Jersey, raised in Roselle. Lived in a small town, you know, very quiet. It was—how you say—you know, a mixture of everybody: Black, white, Spanish, every—you know—everybody—got along together good when I was coming up.

Parks: [00:01:02] I was born in the ‘50s and raised up in the ‘60s, and there was a lot of how you say… Tension, you know—a lot of prejudice, a lot of KKK [Ku Klux Klan] marches, and Martin Luther King, you know… and things was kind of rough. It’s a situation where you learned how to communicate with people. Instead of showing anger and fear, you learned how to talk. You know what I’m saying? “I’m not about that. What you’re doing right now, I’m not about that.” I’m not about that violence and hurting, you know, I’m about showing care and concern and stuff like that. It made me understand there’s definitely different ways of dealing with stuff around you. Instead of going at it violently, you know, and [imitates voice] “Oh, man, I’ve got to go get my gun. They disrespected me.” You know, people [laughs] don’t know how to just sit down and calmly discuss things without rationalizing and doing stuff crazy. That’s what I’m trying to get my mind frame of doing—it’s a better way of doing things, a better way of communicating, better way of talking to people, without the screaming and yelling. You know, it’s communicating, sitting down, and understanding each other. It means a lot.

Lewis: So those qualities, right, in your personality, grew out of experiences that you had—

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: —as a young person?

Parks: Oh, yes.

Lewis: Could you share a story, maybe, of a time that you remember when you had to use those skills, when you were younger?

Parks: [00:02:53] Oh. Yeah, it was back in—the ‘60s… I think, Martin Luther King was like, sixty-three, sixty-four. And I used to go in the area where there was this—you know, it was like all Blacks over here; you cross the street and there’s all whites, [laughs] you know what I’m saying, stuff like that. So, I used to go around in certain areas and play, right? And there was a little friction between the Blacks and whites. And I see them standing out there, and I was like the only Black dude. And there was a bunch of white groups. And I say, “Yo, what’s going on?” And they just looked at me, “Yo, Floyd, we’ve got a problem, man. We’re having a situation. Why don’t you just leave?” That’s the respect they gave me, you know. So, I said… I didn’t know what was really happening until I found out later that there were some people beat up, you know—little race riot and stuff like that. I found out what happened, and then I realized the situation, why they were acting like that. I was in the point of view that they could’ve took their anger out on me, could’ve hurt me. Thank God that I had a little more—how do you say—respect in the area, that they knew me a little better, let me—“Floyd, get out of here,” you know? So that made me, you know… People just have a little care and concern for others.

Lewis: So, you were a kid. You were, what, nine or ten when that happened? A boy or a kid?

Parks: About twelve, thirteen.

Lewis: Wow. And you know, people don’t always associate the KKK with New Jersey, so could you share a little bit about that?

Parks: [00:04:37] Yes. It was—how you say… It wasn’t really KKK. It was people, mostly expressing opinions, you know about, “You all should not have that; you all should not have this.” They were still like living back in the slavery days. Their mind wasn’t adjusted to this is a totally new time and day, you know what I’m saying? That stuff [laughs] is not working no more. There’s a better way of going around things than just forcing and screaming in somebody’s face, you know. Talk to them. Be considerate and polite. It taught me how to— overlook—how do you say it—prejudice. You know, there’s people that I don’t like because they don’t like me. I know that they’re out to hurt me, so why should I like them? I just stay away from them, just try to avoid situations like that.

Parks: [00:05:39] But… Oh!… I’m in my ‘60s, and I just say the things I’ve seen and experienced, you know, have gave me nightmares, [laughs] and they also have given me joy, because I’ve seen better ways of dealing with stuff. It’s a lifelong experience. I’m learning something new every day. In my age, I’ve learned how to talk. I’ve learned how to cope. Something new I’m learning every day, you know. As far as I know, you’re not living if you don’t learn something new.

Lewis: Hopefully.

Parks: Every day you live, yes. I try to relate to that.

Lewis: And you have brothers and sisters?

Parks: [00:06:21] Yes, I’m the youngest of four. My brother Tyrone, there’s my sister Linda, and then my brother Larry, and then there’s me. There’s just my brother Tyrone, my oldest brother, he’s still living. My sister is deceased, and my brother is deceased. It’s just me and my oldest one. But… That was—kind of hard to take. They had some battling with health problems, arthritis, and some kind of other problems. Got the best of them it did, they’re gone, you know.

Parks: [00:07:05] Accepting—because I was like sixteen when my mother passed away. And that kind of sent me off a crazy binge. Like I was cursing everybody out, cursing God out, and hating this person, hating that—"Taking my mother away, why did you do that to me?” I was this angry, hateful little person. Then that’s when I started drinking, and hanging out with crazy folks, and doing crazy stuff, and getting into fights in bars, and getting thrown out of windows. I was a menace to society. Because I was… I didn’t care. I lost all kind of grasp of reality because I had so much anger, so much pain and hurt, you know… I just did crazy stuff, get drunk and go into an all-white bar, [laughs] start a fight. I was crazy like that.

Lewis: [00:08:03] If I recall, you shared that you had worked as an EMT [Emergency Medical Technician]?

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: What was that like?

Parks: That gave me a lot of joy you know, taking people to their appointments, elderly folks who need dialysis, daycares, and I enjoyed that. I did that for about a good two years. It kept me straight, kept me sober, kept my mind focused. It gave me a sense of achieving, you know, made feel good doing something, something that meanwhile is helping somebody else, gave me a good feeling.

Lewis: Where were you living when you were doing that work?

Parks: I was in Long Island.

Lewis: How was it living out in Long Island?

Parks: It was peaceful. It was really like suburbs, really quiet. You know, it had certain areas where there was craziness, and you had [laughs] your peaceful areas, but there was always a little party area where everybody drank and did their drugs and stuff like that. You walk around the corner, there was none of that, you know?

Lewis: [00:09:11] When you were living out on Long Island, you have a family also, children?

Parks: No. I had step kids, but no, none of… No.

Lewis: Did you come into Harlem in the area where we’re at now?

Parks: No, we stayed in Long Island, and that’s where we lived while we was together, for the last—about two years, and then things got rocky, because I met her in the program, and we was both attempting recovery. We was both clean for a year, and we—you know, kind of clicked. And so, I said—I was like forty-seven then—I said, “Let’s get married.” And so, [smiles] we got married. And—down the road everything was going beautiful, like a year or so, and she relapsed. You know, so, I just… I relapsed too, right behind her, so we were all of a sudden trying to kill each other. [Laughs] You know, it just was chaos. So, I just left. I just left the area, left her, and I, you know—

Parks: [00:10:23] came back down this way. And ever since then, I’ve been like, homeless, in and out of programs and shelters and rehabs, just to try to keep myself off the street, try to stay healthy, and try to keep some kind of focus, not let it get to me too much that I’m—penniless, homeless, ain’t got nowhere to go, sleep, you know what I’m saying? I really got tired of the curb, so I used to go into rehabs and programs, stay in six months, ten months, because I figured I needed that. Because I was really feeling… Suicidal. I was feeling really depressed. I suffer from that now, but that was really hitting me real bad, that I really—you know… hurt myself, do something crazy, that would get myself hurt... Calmed down from things and them thoughts, you know. Thank God for people like you all, Picture the Homeless, that made me be able to—how you say—relate and understand and feel and talk, and understand my feelings, and be able to communicate instead of squashing it, holding it in—these feelings, you know—that was really bothering me. I was able to talk and express myself, able to be a person that—be heard and, you know, worth listening to. It’s a good feeling.

Lewis: Well, speaking of being heard and listened to, you are a very powerful speaker and teacher, to let folks know what’s actually happening out there.

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: During the time you were homeless, before you connected with Picture the Homeless, were there other times where you, just on your own—could you tell about a time where maybe you stood up for yourself? Were there times when you saw folks being treated unfairly, that you stood up for them?

Parks: [00:12:26] Oh, yes! Since the seventies. Since like—well, I started—yeah—seventy-three, seventy-two—after seventy-four, yeah, after I graduated high school. I just left home. And I came here to New York one time, just to do some shopping, right? And I just met some people, hanging out, drinking, right? So, I said, “Wow, looks like my kind of folks.” [Laughs] So I came in and I just bought something to drink, and I sat down. All of a sudden, “Yo, man, can I get some?” I started to meet people because I was a little friendly. I said, “Get a cup. You ain’t drinking out my bottle. Get a cup. I’ll give you some.” Then people get the cup, and then they would come and offer me, seeing that I would doing—sharing—so they don’t mind sharing with me. I came to be friends. It was like every day we would chip in, get some money, get something to drink, start the day off drinking, drinking, until all of a sudden that I was just caught up and drinking every day. Like it was just get up, go to sleep, drink, go to sleep, get up and drink some more. It was just like a rut that I couldn’t get out of because it was like—it was crazy, becoming like a lifestyle.

Parks: [00:13:59] That’s how come I had to get out of there and run to a rehab or detox or something, because I felt myself really like, slipping down. Because I seen people that really let the streets get to them really badly, that they just lose all hope and all desires of living. They’re just—there. They’re not living; they’re existing. They’re just taking whatever they get and taking whatever comes to them. It’s crazy that they just like, gave up. They say, [imitates voice] “Oh, to hell with it. Nothing’s going to change.” And I know that feeling. I’ve been there, you know.

Parks: [00:14:40] And I seen—you’ve got to make the change, see nothings coming to you. You got to go out there and get it. There’s an expression that said, “A closed mouth never gets fed.” [Laughs] You’ve got to learn how to speak up and talk, what you want and what you need, and people will be able, hopefully, to listen and understand that there’s truly a need. There’s not just a want—there’s a need sometimes. You need that help from others. It’s a big world, and there’s a lot of good and a lot of evil. You know what I’m saying? You just got to hold your head up and know which way to turn… There’s this old saying, “You got two animals in you—two wolves. And one is a good one, and one is a bad one.” You know, and I said, “Which one is more and more and more powerful?” They say, “It’s the one you feed the most.” The more evil you feed, the more stronger it gets. The more good you feed, the more good it gets. I’ll never forget that saying. I like that. A lot of sense.

Lewis: That’s amazing. Do you remember where you heard that story?

Parks: Oh, I was young… Matter of fact, it was on TV. [Laughs]

Lewis: Yes?

Parks: Yes. It was one of those old— What was it, [Kwai Chang] Caine? You remember Caine? Kung Fu movie?

Lewis: Yes! I used to love that. [Laughs]

Parks: Yes! [Smiles] I think it was a scene from that. Yes.

Lewis: It’s funny how we hear things…

Parks: That click, stay with you.

Lewis: Yeah.

Parks: Yeah.

Lewis: [00:16:32] So, during this time, in the ‘70s, the ‘80s, there was a lot of… There’s always a lot going on in the world. Were there political things that you got involved in, or folks that you heard about that inspired you, that helped you keep your sense of hope?

Parks: Yeah... Definitely—going back to politics, just—you know, around then the Nixon era, the Watergate era. And just seeing how people could abuse power, people can just take advantage of something, because [imitates voice] “I’m the President I can do this.” You know what I’m saying, [smiles] there’s rules and regulations for everything in this world as far as I’m concerned, you know. That taught me, “Because I’m carrying these stripes and this—that gives me the right to violate you, do anything I want to you, because I’ve got this power. That’s how I looked at cops for a long time because they had the power, they had the right, they had the gun—to just come up to me and tell me anything, and whatever I got to do, I got to do it. If not, they’re going to use some kind of restraint, force on me, so—you know. That’s abuse of power, as far as I’m concerned. They got that, so they’re going to use it, sometimes for the wrong. But as I learned, I learned how to walk away and don’t say anything sometimes. Sometimes silence is golden, you know. [Small laugh] So, that’s what I’ve been through, what I’ve seen. There’s a right time and place for everything, to speak up and say your mind. I just—don’t say nothing, walk away. That’s what I learned.

Lewis: [00:18:29] Were there times—do you have memories of times when you didn’t walk away, when you spoke up, and what happened?

Parks: Well… Wow… No, every time I—No negative responses, nothing like that. It was just people said, “You made a lot of sense. I’m glad you said what you said, because it’s true.” People needed—how do you say—focus. Their pain’s a little more than what they’re doing. Instead of sitting back and just watch it happen. And that’s what I’m trying to do, let people know that this is happening to us. It’s out here. This is real, you know what I’m saying? People are being—a month ago, four homeless people sleeping out in Chinatown. They get killed! Because they’re sleeping in the streets. I got beat up in that same area. Yeah, about a couple years ago, about 2014. I had an operation on my leg, I had a blood clot—they stomped me. And they had to open me up and drain blood out my leg. They did a good job on me. Had a concussion, broke my jaw… But… Yeah! It’s that area that I thank God I walked away from, alive.

Lewis: [00:19:59] Could you share some of the other experiences of what it was like for you being homeless out on the street?

Parks: It was—I had to adjust. I had to adjust to a lot of things. Had to adjust—like didn’t know where your next meal was coming from, had to—how you say—had to… Throw away your pride. You know, it’s like, there’s no more pride. You’ve got to ask people, “Can you help me out?” You had to ask people for money. You had to come to people for everything, for your needs, because you had nothing, you know what I’m saying? It was… A learning experience. It was… It was, how do you say it… Definitely had to learn how to… How to let that pride—let that… You got to lower yourself to a certain level that you say, “I’m never going to do that. I’m never going to be there. That’s never going to happen to me.” But all of a sudden you’re in this situation that, wow, I’m somewhere I never said I’ll be. I’m here, and I’m begging. I’m asking people for money. I ain’t took a shower in three or four days, you know. And things that I’m not used to doing, all of a sudden—I’m throwing… [slaps table] Handle that. You know, this is your life from now.

Lewis: So, we’re videotaping this interview. What do you want people to know? What do you want people to think when they see somebody who is street homeless and asking for money? How do you want them to treat folks?

Parks: [00:21:54] Well, I want them to be more considerate, especially the person that’s coming to ask you for money. You know what I’m saying—sometimes, their approach is very rude, and very, very—not considerate, not being a gentleman “Oh, can I have—?” They don’t know how to talk to people, how to walk up, “Excuse me, sir. God bless. How are you doing? I’m trying to eat and get by.” They got their ways of doing things.

Lewis: The public that’s not homeless, what do you want them to understand?

Parks: [00:22:32] Oh, what I want them to understand. That we’re people of need. We don’t mean them any harm when we’re coming to them and talking to them. Some of us are really serious about trying to get something to eat. Some of us are trying to better themselves. And some are just trying to get the money to get themself a drink that they probably do need badly, to get themself what they need to get through the day! You know what I’m saying?

Parks: [00:22:54] To survive out there in the street’s not easy. Sometimes you’ve got to cope with that drink and that drug just to get through the day—the situation you’re in. Living in the streets is mind-boggling sometimes, the things you’ve got to deal with, the people walking over you, around you. You don’t know who to trust, who’s going to hurt you, who’s going to do something to you, because it could happen just like that. Somebody could just do something to you because you’re just laying out there, vulnerable, in the middle of the streets. That’s why it’s dangerous.

Lewis: [00:23:30] You know, talking about the danger and being vulnerable, when we met you, you were part of a community of folks staying under the Metro-North.

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: What was it like for you? How did you meet the folks that you were with? What kind of community did you form?

Parks: It was just—it just come to be. A bunch of people didn’t have anywhere to go, nowhere to sleep, found an area where they might find some peace without being interrupted—cops coming and waking them up. We all come to be a community. We all come to—like a village! Just come to get to know each other, come to get to help each other. You know what I’m saying? “I’ve got something that you don’t.” Share—you know what I’m saying? We come to—help each other, because we’re all in the same situation, all walking down that same street. You know, we try to—look out. You figured people that are sheisty and no good, that you try to separate yourself from them, because as soon as you close your eyes they’re going to be in your pocket. You’re trying to find people that you can trust, somebody to look out for you, and you look out for them—some kind of understanding. There are some good people out there that fell into the hard times and all of a sudden they’re in the street, but they got a good heart, got a good soul, but they’re homeless, you know?

Lewis: How long were you up here, around the Metro-North, around this area, homeless?

Parks: Oh, maybe about a good six, seven years. Since 2014, ‘12, ‘13, something like that.

Lewis: [00:25:23] You mentioned the police a couple times. Could you tell us about some interactions that you had when you were out there with the cops?

Parks: Oh, just we… Congregate together, we’re talking, and probably a little drinking and whatever. We were just gathering. And the cops would just come along and say, [imitating them] “Yo, you got to go. You got to break this up. You got to leave.” I said, “Where are we going? I mean, we have nowhere to go. Where are we going?” [imitating police] “You’ve just got to leave here. I don’t care. Walk around the corner. Do something. Just get out of here.”

Parks: [00:26:01] Because they’re probably getting complaints from the community, that all these… “Look at all these people; what are they doing?” So, the cops come, and they tell us there’s too much of us, there’s too many of us, so we got to scatter out, we got to separate. And they harass us. We go over there. They come over there and tell us, [imitating police] “No, you can’t stay here. You’ve got to go over there.” We go over there. “Oh, we got complaints, so you’ve got to—” They’re just, like with cattle, just move—herded us around. It becomes aggravating, becomes frustrating. You know, you relax and all of a sudden, [imitates police] “You got to get up. You got to go.” I said, “Yo, man, I just—” [imitates police] “I don’t care. You’ve got to go. You want to go to jail? Go to hospital? What do you want to do? You’ve got to leave here.” And so, I just get up and go…

Parks: [00:26:49] But… It’s rough. It’s definitely something I wouldn’t wish on my worst enemy… This situation. It’s bad enough being homeless in the streets. Then you get harassed by the cops every day. You can’t sit down. You can’t rest. Oh, you got to move here. You can’t stay there. Then you caught yourself… You’re being isolated now—because every time you’re around a crowd, here come the cops, so you’re being by yourself and just trying to get some peace.

But… It’s a struggle. It’s a mind-baffling—You don’t know which way you’re turning to, don’t know which way you’re going the next day, how you’re going to eat—whatever... It makes you angry, because—wow… Why is society… Why am I in this situation? Why am I… Why am I… Why? There’s got to be a better way, you know? The only better way there’s going to be is by letting somebody know how it is, to talk about it.

Lewis: Do you recall, or could you talk about, the time when you first heard about Picture the Homeless?

Parks: [00:28:11] Oh, yes! I was—right there by—across the street from Metro-North. That’s where we was living, had that little gathering, right in that area right across the street. And somebody… Was being harassed and talking to Nikita [Price] about this stuff, right? And he came and said, “Anybody need any help, any assistance with anything?” I said, “What can you offer? What you got to offer?” He said, “We can… Talk to us. Help us know what your problem is. Explain your situations. Let us know what’s going on, how can we help you?” That’s how I got into it.

Parks: [00:28:50] I started talking. He said, “Oh, I like the way you talk. You want to talk? There’s a place in—” I said, “Oh…” Then I got speaking in places and learning how to communicate and let people know what’s going on, and how things are out there and what people are really going through.

Lewis: [00:29:12] There were quite a few folks that were staying under the Metro-North, in the village, but most folks were not coming into the office and coming to meetings. And so, were you taking information back out there? Did you go out there?

Parks: I let them know, yes, there’s something—yes, definitely. Something they needed to hear or get into. “Definitely, if you want to get out of the situation you’re in, they’ve got some good steppingstones. They’ve got good organizations—like Breaking Ground, you’ve got CUCS [Center for Urban Community Services]. You’ve got people that they connect you to, to help you get off the streets. If you’re serious about that, you ought to check it out!” That’s what I used to tell them. Some came, some didn’t. Some of them, they’re so used to that—streets, it’s like… It gets hold to them and it doesn’t want to let them go. They don’t know what other life to live but the streets. You know, they’re just drawn to it. It just doesn’t let them go.

Lewis: [00:30:21] Was there a time that there was somebody that—didn’t come in, didn’t get involved, but they started to get involved, that surprised you?

Parks: Yeah… Yes, definitely Country [Travin Saunders]. [Laughs]

Lewis: Yes? Talk about that.

Parks: Because he was so rambunctious, so wild. Like, he was so carefree that he didn’t need anything. He had everything under control. “I don’t need any help from anybody. I got it. I got it.” He was one of those persons that didn’t need nobody. Like everything was under control. He had it a-okay—but you know, he didn’t. He was living that fantasy, thinking everything’s okay, and things are tore up.

Lewis: What changed? What do you think changed, in terms of his relationship with this organization? How did that happen?

Parks: He seen how the help, the situations, the things that he could accomplish that he wanted to accomplish, and needed to, he couldn’t do it on his own. He seen how much this place can help him, how much they can—how you say—doors could open up. People can advocate for you, speak up for you, stuff like that.

Lewis: [00:31:48] You participated in a lot of press conferences—

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: —and sleep-outs. We did a sleep-out—

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: —under the Metro-North. What impact do you think that activism had on folks who were staying out there?

Parks: Oh, definitely, it’s to let folks see and know, take a good look at situations—because they don’t know what’s going on. They don’t involve themselves in that. It’s got to be something that’s got to be put in their face, you know what I’m saying? Something they’ve got to see, something that they can’t just walk around, something they’ve got to listen to, you know what I’m saying? You’ve got to put it in the position that they’ve got to stop and hear what’s going on. They’ve got to make it interesting, got to make it understandable that this is a necessity… somethings got to change.

Lewis: [00:32:42] What are some ways, do you think that together we made it understandable for people that weren’t involved so they could get involved?

Parks: Oh, the communications! The word of mouth—letting people know what’s going on, and interviews, the conversations, the things that’s being done. You know, people see good’s happening, something good is accomplishing, [imitates voice] “Let me really check this out. Wow, I didn’t know they were doing that, like that.” People come up to me and say, “Oh, man! I seen you on TV the other day. Man, I like what you said…” I said, “Wow, are you going to help out or what? Are you going to join in?” He said, “Yes, no doubt. How do I do that?” “Go around the corner to 126th Street—Picture the Homeless.”

Lewis: You started doing outreach, I guess, in a way.

Parks: Yes! I would definitely spread the word. That there’s definitely a change out there, and if you want it, it’s right around the corner.

Lewis: [00:33:51] How was that for you, becoming—a part of the organization, and helping to encourage other folks to join in? How was that?

Parks: That was a good feeling. You know? That made me feel good, because I was helping somebody help themselves, which was helping me. It’s a repeat cycle, you know?

Lewis: [00:34:16] Do you remember when you first came to the office, what your impressions were?

Parks: [Imitates himself] “They can’t do anything for me here! Nah, they’re a bunch of—just trying to get some publicity and get some money in their pocket. They ain’t serious.” Until you got to know them, started being around them, started dealing with them, see how truthful… And the message they was spreading was about something you definitely want to get into, something that I seen the need for. Definitely.

Lewis: [00:34:54] I can share my impression with you when I first met you is I thought you were really powerful.

Parks: Thank you.

Lewis: And as I shared before the interview, the fact that you were speaking in public, and then still street homeless, and you were speaking out against the Police, the 25th Precinct particularly, but there were other—Borough… North—all kinds of cops were around here then.

Parks: Yes, [unclear] yes.

Lewis: You were actually—in danger by speaking out.

Parks: Yes, retaliating yeah.

Lewis: [00:34:48] Were there cases of retaliation that you can talk about?

Parks: They just—would… There was one time… I was crossing the street, right? I was not actually on the corner, but—I was jaywalking! And this cop came along, pulled over, and said, “Mr. Parks, you were just jaywalking.” He knew my name and everything! You know what I’m saying? And they sent me a letter. They threw that out, you know what I’m saying? Because you know… They knew that was bogus. They knew that that was retaliation, you know. And they sent me a letter saying I don’t have to even go to court for that. They knew that it was—how many people jaywalk these days and get tickets? Nobody. Everybody’s jaywalking, now all of a sudden out of one million people I’m the only one getting a ticket for jaywalking? [Laughs]

Lewis: Mr. Parks. [Laughs]

Parks: Yeah! What is that? That what showed me right there… To watch it.

Lewis: [00:36:01] You were part of a delegation that went to speak with the Inspector General of the NYPD [New York Police Department].

Parks: Oh, yes. Okay, wow.

Lewis: Could you share what that meeting was like?

Parks: That meeting was… That was a meeting to make them look like they’re going to do something, make them look like there’s a possibility that they’re going to listen to us. Therefore, they’re—putting on a show, to me—just to make themselves look good, that they had us there, that they attempted to talk to us. They were saying nothing but, “We’re going to do this, we’re going to do that, we’re gonna, gonna, gonna, gonna, gonna…” Ain’t nothing being seen, and nothing— We said, “Well, you said this—a year ago and there’s nothing being done! You’re just—all you’re doing is blowing smoke up our asses.” You know? That’s what the kind of meeting was to me.

Lewis: Looking back, was it still important to do that meeting?

Parks: Yes! We definitely had to express our opinions, express our views, express the seriousness of the change, the reform that needs to be done in the Police Department. It definitely was important that we got heard and listened to, even though there wasn’t too much done about it. But we was there, verbally, and seen, physically—to let them know that this ain’t right, something needs to change!

Lewis: [00:38:19] So, we were looking at a video of an incident that happened on October 2nd, 2015.

Parks: Uh-huh.

Lewis: when—could you describe what that incident was?

Parks: Oh, yes. It was just me and a bunch of homeless people got together, and we used to sleep by the school, right? We all were sleeping there that night, by the school. Everybody had their property, had their areas, laying down, sleeping. All of a sudden the cops come along, flashing flashlights in our faces, kicking us in our feet, telling us we’ve got to get up and move. I said, “Okay.” I’m getting up to move. I take my cart, and they said, “Where are you going with that? No, that’s stolen property. That’s got to stay here. That’s going in the garbage.” I said, “That’s all my belongings!” He said, “Man, if you don’t get off of that and move we’re going to lock you up.” I said, “That’s my property!” He said, “You’re going to keep it up, we’re going to lock you up. You just walk away.” So, I just walked away! I mean, they just took my stuff and threw it in the garbage can and crushed it up, you know?…. And—that was it.

Parks: [00:39:31] Then I was talking to Picture the Homeless about it, and these lawyers—what’s it—advocates? Who were these people?

Lewis: The Civil Liberties Union.

Parks: Yes, Civil Liberties Union.

Lewis: Alexis [Karteron].

Parks: Alexis, yes. She got some video cameras of the school and showed exactly what they did to us. You know, that was very beneficial, you know, seeing is believing. And they said, “Oh, that’s right there on camera, black-and-white.” So, they couldn’t lie out of that one! So, that was a good experience you know… To be heard and be seen—that this is what is being done to us out there.

Lewis: [00:40:14] What did you have in your cart?

Parks: Oh, some clothes, some documents, Social Security card, my wallet, and a little jewelry—a chain—it’s probably worth thirty or forty dollars—and that was it.

Lewis: Was there medication and other things like that?

Parks: Yes! Yes! There was some blood pressure medication that was in there, and some vitamins.

Lewis: And Alexis Karteron was the attorney with the Civil Liberties Union—

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: —and there were several people that lost their belongings, but there were three, including you—

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: —that were part of a complaint.

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: [00:41:02] Could you talk about what that process was like?

Parks: Oh, that was—how you say—that was… It let me understand—the decisions that had to be made; the decisions that had to be done; you know. I had to decide did I want to go along with this, you know, and have this—and looking over my shoulder, worrying about cops messing with me, or do I continue on to fight this. And I said, “I’ve got to continue on! I’ve got to make this mission known. They just can’t keep doing this stuff, and people just turning their back, letting them do it. If they see it, they don’t say nothing. I mean, it’s got to stop. The way that we’re being treated out there, the way we’re being put in situations as—you know, in harm’s way. That’s got to stop.”

Lewis: So, there’s a quote from you in this article that says: “Thank God for cameras. It showed the abuse that they had done to us.”

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: In this article in the Daily News.

Lewis: [00:42:14] When you all left the plaza across from the Metro North station, did you leave there voluntarily,

Parks: No

Lewis: and just go to the school?

Parks: No

Lewis: How did you all even end up there?

Parks: We was told we couldn’t stay down there no more. We was told, “Go up the block! Go up to the school.” We was told to go up in that area because they couldn’t see us. We were out of sight, out of mind, I guess. We was eyesores. They didn’t want to see all these homeless people laying and sleeping out there. They just wanted to move us and get rid of us to another area as soon as possible. So, they said, “Go down there to the school”, which was 127th Street, and that’s where we started sleeping.

Lewis: Were the neighbors around the school—did you ever have interactions—? What were interactions with them like?

Parks: No. No, because we had—the security lady, that did security for the school would wake us up like six in the morning and we all would just leave. We would go there, and we’d clean up behind ourselves. I mean, we never left no mess. We always tried to make it good for the next day—we’d come back, we’d have no problems. We always tried to clean up behind ourselves and stuff like that.

Lewis: [00:43:28] Who were some of the other folks that were staying up there around the school?

Parks: Oh, it was me, Chyna, Doc—wow. They had Triple R. They had Triple R. Was it Country? Yes, I think Country was there, too… I think Rick was there. That was it… Nene! I think Nene was there.

Lewis: [00:44:01] When you all filed the complaint with the Comptroller’s Office, what were you asking for?

Parks: I was asking for some kind of retaili… “I’m sorry,” I mean, would have… “What we did was wrong.” One of the lawsuits proved that they were wrong. I mean, I wish it could have been a lot more, but just the fact that we did win, the fact that it was done to us, you know what I’m saying, and it’s documented, that made it a little better, somewhat, that showing what’s happening, what they’re doing.

Lewis: And so, they had you… It says here, “The de Blasio administration has agreed to pay the men, three men, a total of $1,515.” They have you quoted here: “What they did was an atrocity.” The money that the City gave you all was compensation for what you lost—

Parks: Yes, yes.

Lewis: —not for pain—

Parks: Pain and suffering.

Lewis: No.

Parks: True that.

Lewis: How was that for you?

Parks: Not too good. I mean, I just had accepted, because it seemed like it was something that couldn’t change. It was too late. It was done, boom, so we was—taking a walk with it.

Lewis: When the complaint was submitted to Scott Stringer, the Comptroller, you all went up into his office.

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: How was that? What was that like?

Parks: That was a little uplifting, a little—It made me feel good that something is finally accomplished out of this, something good is coming through it.

Lewis: And this article was in January, right? This went on through that winter, and during that time you were still street homeless?

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: [00:46:07] Months later, in May, we filed a complaint with the Human Rights Commission, with the same lawyer

Parks: Okay.

Lewis: about the NYPD profiling homeless people.

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: And you were also part of that, and we hand-delivered the complaint to the Human Rights Commission. Even though we don’t see—we don’t get—win everything we should win, you mentioned before that it’s still important to speak up.

Parks: Yes, yes.

Lewis: What do you say to other people who say, “Oh, well, nothing changes”? What do you say to them?

Parks: I say to them, “You’re wrong man. You’ve got to make the changes. Ain’t nothing going to change unless you make a change. You know what I’m saying—you’ve got to stand up and be heard for what you want done! If not, it’s not going to get done.”

Lewis: [00:47:01] Has this changed you at all, doing these things, changed your life?

Parks: Yes! It gave me a little more feeling about myself. My self-esteem was, you know, was really shot. It made me see that I’m… I can do something, you know? I can do something that’s worthwhile, that I can accomplish something and help others to accomplish something.

Lewis: And you still have a relationship with Nikita, the organizer—

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: —Picture the Homeless. What is it like for you to be part of Picture the Homeless?

Parks: It gives me a feeling of achieving something, a feeling that something’s going to be done, something’s going to benefit somebody in the long run. Somebody’s going to come out with a smile on their face, achieving and making their life better. And I’m doing something that’s going to improve that.

Lewis: [00:48:02] Now, you’ve since got a place to live—

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: —and you still come and visit the people that are your friends.

Parks: Oh, yes.

Lewis: I understand cops were telling you, “Why are you here? You have a place to live.”

Parks: Yes!

Lewis: Talk about that. Talk about what that’s like.

Parks: That’s like… They’re aware that… Of me. You know what I’m saying? They know who I am. They know I’ve got a place to stay. They know my vocal expression on what was being done. Sometimes they come at me; sometimes they’re leery, you know. Because… They see—I don’t know. They see me as—I don’t know—as somebody to be reckoned with. In some ways that’s good; in some ways that’s bad. They know I’ve got something, and that I’ve been verbal, and they know that when I talk somebody’s going to listen. I’ve got a little clout to help me be listened to, to express myself and what’s going on.

Lewis: [00:49:15] What you’re looking at is a press release that we did when they were first moving you all from under the Metro-North, and officially they actually created a policy of using “move on” orders.

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: Like you said, you have to leave, but where do you go? So, what… How does that impact somebody who has nowhere to go, to be told by a police officer—

Parks: It’s very aggravating. That’s very… It makes them angry! Because, you know, we’re not doing nothing, breaking no law. We’re not blocking no traffic. We’re being on the side. I mean, we’re really not breaking no law—so why are you bothering us? It’s just, how do you say it, they call us “eyesores”. That’s what’s happening… They don’t want to see us. They don’t want to look at us. They move us over here, move us over there. They don’t want us—how do you say it—on the main strip, with a lot of people, with tourists—and they don’t want to look at us! They want to push us to the side. That’s what they’re trying to do.

Lewis: [00:50:31] Before we took our break—now I remember—we were talking about the incident on 126, when the cops came in a van, and they were taking y’all’s milkcrates—

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: —saying it was stolen property.

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: Could you walk us through and describe, like… What did the cops say [oh, and watch the wire, please—thanks, sorry!] What did the cops say to you? What did they do?

Parks: They just said we’ve got to move. When we get up, they take our crates and they put them in the police car. Sometimes, like when we’re sitting on the wall over here, they just throw them across the wall. Now we can’t get to them. They did that a couple days ago! They just took their crates and just threw them over that wall.

Lewis: One of the things that stands out for me, in that incident, was the police officers were putting on gloves.

Parks: Yes!

Lewis: What do the gloves mean?

Parks: The gloves mean that they’re too good to touch us. That we’re not worthy of being touched without gloves. Yeah, like we’ve got a disease or something. Yeah.

Lewis: We’re looking at this photo of the police officers putting on a pair of blue gloves, and I remember you saying to the police officers—because they put the gloves on, and then they would snap them, pull them back,

Parks: Yeah.

Lewis: and they made a little snapping noise.

Parks: I don’t know what that meant.

Lewis: And it almost seemed like a threat, like “Here we come”, or something. And you were saying… You stood up and said, “We’re not animals.”

Parks: Yeah!.

Lewis: “We don’t have a disease.” In what ways did the police react when you said things like that to them?

Parks: Nothing. They just looked at me like—they just shrugged it off… Like it was nothing. Like they didn’t care what I thought, what I felt. They just had a job to do, and they was going to do it. Boom. If we’ve got to move, they were going to move us. You know what I’m saying? That’s how they say it. “It’s from high up. I was told to do this. I’ve got to do it.” That’s what they were telling us. “We were told to do this. We got complaints, and they tell us we’ve got to move.” Complaints from who? For what… It’s crazy.

Lewis: [00:53:05] What would… What are the solutions to—? Obviously, people on the street don’t want to be on the street. People would like to move on—but to where? What, for you, would have been a solution, as opposed to creating a problem?

Parks: Oh.

Lewis: What would have helped you?

Parks: I—[laughs] Wow. The help that I’m receiving now! The help that I’m getting now. People see the situations—you know, the organizations, and there’s people out there that can guide you to the right place that can exactly help you, what your needs are. But you know, I’m saying—

they’re there, but they’re not easy to grasp to, but you’ve got to be able to reach out and try to find these places. If not, you’re not going to get to them, because they’re not exactly right out there in the open. You’ve got to be connected, affiliated with some kind of organization that can refer you to these places. If not, it’s sometimes really difficult to get into.

Lewis: [00:54:24] I remember a time that you were going to a meeting—maybe it was with the Inspector General of the NYPD—and Nikita spent the night here in the office.

Parks: I think I did, too.

Lewis: With you.

Parks: Yeah.

Lewis: What did that mean to you, that he did that?

Parks: That means… It showed his seriousness, [laughs] the realism, the things that they’re doing. It means something to them. They’re not just doing it. I mean, they feel it, they’re part of it, and they live it. It’s what they do! That makes me feel good because they’re serious. They show their seriousness, they show their professionalism. They show their understanding of what’s going on.

Lewis: [00:55:16] When we first started getting to know you, and Sarge, and Doc, and Chyna, and Jesus and everybody, one of the things that you all wanted to do was to cook a meal, and you and Sarge bought some T-bone steaks—

Parks: Yes! And we—

Lewis: —and had like a cookoff. [Laughs]

Parks: There were some chicken wings, and turkey legs. [Smiles]

Lewis: How was that for you all, to be in here and using the kitchen, and—?

Parks: That felt good, doing something positive, helping people out that, you know, need it. That was a good feeling. I was able to do that.

Lewis: Were there other fun times that you had here with Picture the Homeless?

Parks: Yes! There were a couple of cookouts in the back here, had good times, good dances. Especially the dances we used to go to when I was able to dance. Now, all this arthritis and everything is messing with my legs. Thank God I’m still able to move around like I am. I ain’t getting no younger. So, I’m trying to do the best I can.

Lewis: [00:56:77] And even though you have housing now, you’re still involved with Picture the Homeless.

Parks: Yes!

Lewis: Could you tell why?

Parks: Why? It gives me something to occupy my mind, gives me something to do, gives me something positive instead of going and hanging out. I’m achieving something. I’m accomplishing something that makes me feel that I’m doing something good—to benefit myself and others. It makes me feel like—it’s a reward, to me, to show that something positive can be accomplished out of all this misery.

Lewis: [00:57:08] For the City to really end homelessness, what needs to happen?

Parks: What needs to happen? They need a little more—how you say… What is that word? Constructive living? I mean, they need a little bit more places that is going to have counselors and going to have doctors. I mean, they need more places that are going to have everything they need, right there. I mean, you’ve got some people that’s really, that has some serious mental problems. That’s why they’re in the street. That’s why they don’t want to come out the street, because their mental state of mind, they feel so comfortable where they are, and they don’t want to go. They just totally, “I’m not moving. I’m happy. I’m okay. I’ve got my drinks. I’ve got my drugs. People come and feed me.” You know what I’m saying? Some people get content. They don’t really want to make that serious move of seeing something better in life. They’re just happy where they are. That bothers me a lot though, you know, that people let themselves get twisted and wound up, and suddenly it clouds their thoughts of reality. They’re just stuck in this wonderland—of phoniness. It’s not real.

Lewis: I know that you’ve said a couple times in this interview how much folks that have given up hope really worry you, that you really—

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: —care about that. Are there other folks that are out there who haven’t given up hope but who can’t find a way out?

Parks: Oh, yes. There’s still a lot of them out there that consent with that life that they got. They don’t see… That there’s no need for no change. That’s the way I see it, because they’re constantly doing the same stuff over and over and over and over again, and expecting different results, but it stays the same. Nothing changes—to a point that they’re comfortable. They don’t want to change.

Lewis: [00:59:33] You have a home now, but you still come around—

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: —and have your relationships with the folks—

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: —the village. What is that like for you?

Parks: That’s like going to see friends. Seeing how they’re doing, making sure everybody’s still alive. You know, it’s rough out there, and you wake up, find yourself in the hospital, don’t even know how you got there. It’s a challenge. It’s taking a lot of risky chances, being homeless in the streets these days. The craziness, the things people are doing, you know, it’s scary.

Lewis: [01:00:24] Do you have any final things that you want to share about what Picture the Homeless means to you?

Parks: It means hope. It means achievement. I have achieved something since I’ve been here that I probably wouldn’t have, you know. I’ve got a place to lay my head. I see a little more of my pride and my dignity and my self-respect coming back, because I’m not doing these crazy things that I had to, to survive in the streets. It’s a frame of mine, you know. I had to readjust and rethink my way of life that I used to do. I can’t do that no more. This habit, I can’t do this no more. I’ve got to start doing this. It’s adjusting. There’s a lot of adjustabilities, adjusting to the homelessness, and then coming back to having something, and you’re used to not having nothing, and you’re used to this. Then you’ve just got to get more responsible. I got to get more determined. I got to get more active, you know what I’m saying? It’s this frame of mind. I’ve just got to be ready, prepared for certain stuff.

Lewis: [01:01:47] It sounds like two things were happening, and have happened, with your relationship with Picture the Homeless, that are connected. One is help getting a place to stay. But the other is having a place to stand up and speak up for your rights—

Parks: Uh-huh.

Lewis: as a human being.

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: Those things aren’t the same things, but they were both happening here.

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: How… Could you talk about… Because there’s a lot of places that provide services.

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: What’s the importance of having both of those things kind of in the same organization, where you get help, but you also have rights, and—?

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: What is that like? What was that like? How did—

Parks: That’s like a good feeling, that you know that there’s somebody that’s there that’s going to listen to you, somebody that’s there that’s going to see the seriousness of what you’re saying, somebody that’s going to be open and going to be considerate of your feelings and your thoughts—put everything in perspective, you know? The honesty, the openness, you know what I’m saying—you’re able… “What’s on your mind? What do you need? To be able to express yourself, instead of holding it in? “They’re not going to understand me.” Just talk! Be heard. They will understand. You’ve just got to be more vocal of what you’re going through, instead of holding it in, and then all of a sudden, I hold it in and wind up doing something crazy instead of expressing myself and letting it out, you know, rather than talk.

Lewis: [01:03:33] Some places, some organizations—you know there’s like theories about all of this kind of organizing and stuff, and so some places have actual policies of not providing services, of just doing the political work.

Parks: Hmmm.

Lewis: I think Nikita is somebody that does both at the same time.

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: If Picture the Homeless was a place that only provides services, and didn’t address the rights and the dignity—would that have been different? How would that have been different for you?

Parks: Oh, definitely! It would have been different because they’re not looking at what’s needed to be done. They’re just looking at—how you say—impressing. I mean, impressing, trying to look good, you know, and just not doing nothing else but there. They’re not really helping nobody really achieving nothing. They’re not really accomplishing anything that somebody needs done. They just happen to be—a storefront—just there, you know?

Lewis: Other groups—for example, I was talking to a group the other day that provides a legal clinic, so they help people, but they don’t talk about the root causes of what’s causing the problem. So, it’s like, “Here’s a lawyer; you can go to Housing Court,” but not talking about how to actually change the system. These questions, one of the reasons we’re doing this project, is to really analyze the work of Picture the Homeless, and what are the lessons.

Parks: Nice.

Lewis: [01:05:24] And so, you, as somebody who’s a leader at Picture the Homeless, in this way, are a teacher, because you can help us, you can help all of us together, understand how Picture the Homeless does things in a way that actually do make a change, do help.

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: That’s why we’re trying to get to these kinds of questions of—

Parks: Oh, yes.

Lewis: —if Picture the Homeless wants to understand itself, and what worked, and what didn’t work, from your perspective, you’re the best person to be able to explain that.

Parks: What works, what didn’t work?

Lewis: Uh-huh.

Parks: Far as I know, there’s nothing that didn’t work! Everything they tried to go out to achieve I believe we accomplished, or it’s still, how do you say, pending. Nothing really—that didn’t happen that we didn’t go out to make happen. Everything that we planned, everything that we organized went through smoothly, because it was organized and done professionally, and it was done with the backing of people that really needed and wanted this to happen.

Lewis: You know, in the news, like looking at California, you’ve probably seen there’s so many homeless encampments.

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: [01:06:45] What would you suggest to people who are homeless in other places? What can they do if they’re trying to start organizing?

Parks: What can they do? Wow… They got to get together. That somebody’s got to be some kind of leader to go in front of these people at City Hall, go in front of these people who, how you say… What do you call them people—who take property? Developers, who’ve got property, who can— Some kind of way that they can benefit, and everybody benefit, you know, through this connection of having this housing. Definitely needs housing, definitely need some kind of structure, some kind of plan, some kind of knowing where they’re going to start and what they want to achieve at the end, you know. Somebody’s got to know how to go about this! And that’s why I like Picture the Homeless because the way they went about this, the way they was doing things, the way… I felt that I got so much accomplished because people believed in what was happening and what was going on, and they didn’t want to just listen—they acted. They responded. They made things happen! That’s what—

Lewis: You mentioned the importance of action—

Parks: Yes.

Lewis: —right now. Not just listening and planning and knowing. Because we could be geniuses and know everything—

Parks: Yes. [laughter]

Lewis: —but—

Parks: Putting it to work, yes.

Lewis: [01:08:30] Putting it to work. Do you have a favorite memory of an action that you participated in that you want to share?

Parks: Wow. [Laughs] Wow… A favorite—all of them was uplifting. Every time I spoke, I got something out of it. All of them was challenging, and rewarding, and very helpful for me.

Lewis: And the planning that would go into that, what were some of the things that you were involved in, in planning to make those actions happen?

Parks: Oh! Wow. Sitting back and looking at what’s going on, sitting back, and discussing, seeing what needs to change, talking and relating to the whole perspective of what we’re trying to accomplish, where everybody comes to some kind of agreement, and we try to go out from there.

Lewis: Were there times when people didn’t agree?