Charley Heck

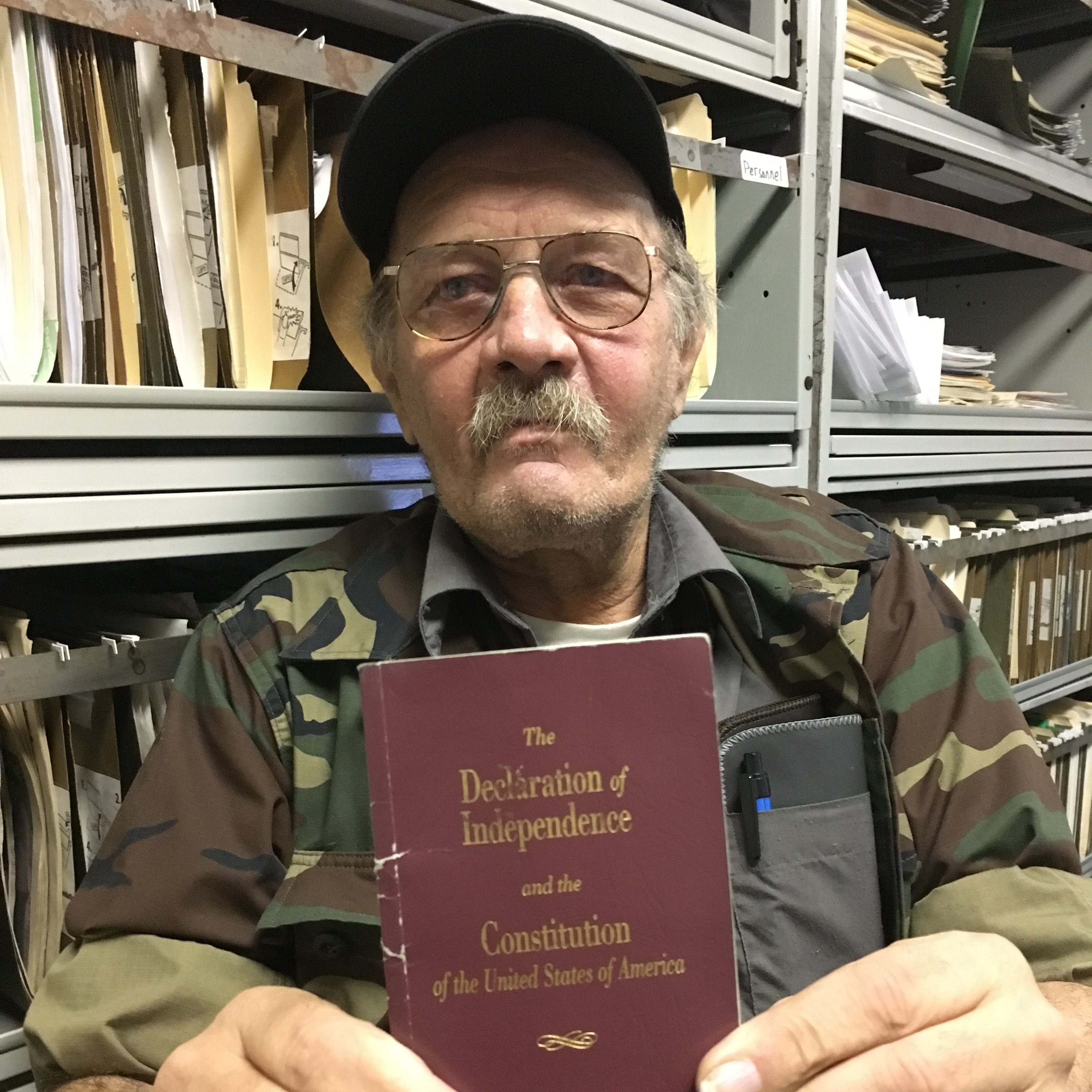

The interview was conducted by Lynn Lewis with Charley Heck, in his apartment in the Bronx on December 12, 2018, for the Picture the Homeless Oral History Project. Charley is a longtime member of Picture the Homeless (PTH), meeting PTH in 2004. Joining the civil rights committee he inspired PTH to form the Potter’s Field campaign and became a leader of the Canners campaign. This interview covers his early life and experience being street homeless in NYC, and meeting PTH.

Charley was born in Middletown, Connecticut and is the oldest of three sons. “My mother died when I was eighteen years old, and my father was this cruel, abusive criminal.” (Heck, pp. 4) He details the abuse at the hands of his father, who was a trapper and hunter, including an incident where he blinded Charley in his right eye. His brother Joseph was valedictorian of his class, but Charley struggled in school, graduating with a high school diploma, and was drafted into the Army during the Vietnam War. Although he was blind in one eye, they waived the eyesight requirement. He youngest brother was mentally retarded and was removed from their home by the State after Charley and his brother left home. At age 18 Charley went to Vietnam. His grandparents were in the military. “I mean, I wasn’t really against the Vietnam War, and I wasn’t really for the Vietnam War. I mean, I thought whatever they asked me to do, I will do it and so I submitted myself to the military draft. (Heck, pp. 6)

“I remember flying over the country of Vietnam and looking out the window, and the ground was covered in water-filled craters. It looked like every inch of the ground had a hole in it. So there really was a war going on there. I got to my permanent duty station, and immediately—as we were landing in the base camp of Quan Loi, the camp was getting hit with rockets and mortars. And so, that was really my heaviest action that I saw in Vietnam was on my very first day in my duty station!” (Heck, pp. 7) Afterwards, he describes becoming so used to gunfire that he slept through it. Charley was exposed to Agent Orange, “we were considered “detail men”, and we would be paving streets. Now, what they use for pavement is not asphalt. It was this really oily stuff. It was kind of like an oily tar, and we would work with that stuff. In that tar of course, they put the dioxin—what I’m suffering from is effects from dioxin poisoning, and they use that stuff to kill the weeds... I mean, they would send us out as detail men to kill the weeds in the barbed wire with this stuff. And that was—that’s my exposure to the Agent Orange. Agent Orange used to come in fifty-five-gallon oil drums, and it had—it’s got its name from the armed stripe around the outside of the oil drum.” (Heck, pp. 9)

Towards the end of the Vietnam war, he was discharged and returned to Connecticut, working as a garbage man, “I had this rage. I had this fiery, consuming rage. It was—I was in this stage of confusion like I was walking around as some kind of mixed-up kid! And this completion of the military service just… It just fortified this burning rage and it—what was driving me crazy. And… So, after a couple of years as a garbage man in Waterbury, this rage consumed me, and I couldn’t seem to hold on to any meaningful job or meaningful employment.” (Heck, pp. 12) After years of drinking, he ended up on the Bowery in NYC, attempting AA and other meetings for alcoholism, but they didn’t help. As a child he attended church with his mother and two grandmothers and connected with a sobriety program at a Franciscan monastery, but returned to Connecticut to construction work on luxury homes after two years.

Charley reflects on his experience in shelters, describing staff abusing their authority and returning to the streets. He also describes police abuse, and successfully sued the NYPD. “I’m a homeless man living on the street! I won a case against the City of New York and the police department! They awarded me eight thousand dollars… But! It took the city comptroller seven years to sign the check.” (Heck, pp. 15) He also describes meeting Joe Gilmore and the Midnight Run. Charley began supporting the organizing of what would become the Midnight Run while he was still street homeless, becoming the first Chair of the Board of the Midnight Run. Charley describes how he survived living in the street, including knowing the soup kitchen schedules at different churches in Manhattan and refusing a psychological evaluation in order to get housing.

“I joined Picture the Homeless in 2004. This is—2004 is like after more than twenty years of already living in the street. I heard that there was a bunch of people on 116th Street in East Harlem that were doing something about police brutality and harassment and unlawful arrest and so I took the time to investigate for myself what this was all about. And that’s when I joined Picture the Homeless.” (Heck, pp. 20) He describes being sent by a judge to the psychiatric ward at Bellevue, “After two weeks in Bellevue Hospital, the doctors couldn’t find anything wrong with me, so they had to release me. That was another incident. So now, I talked about two incidents with the police, but there must be several dozens of times that I had altercations with the police.” (Heck, pp. 20) Charley describes his first impressions of the PTH office as well as his experience with homeless advocacy groups.

Charley was invited to a PTH protest of [mayor] Bloomberg’s five-year plan to end homelessness, “because his plan did not involve the people that actually lived on the streets. It was all politicians and big real estate interests.” (Heck, pp. 21) The next protest was during the 2004 RNC, “They were going to close the window in the Post Office that handles all the indigent persons—no address... That window is on Ninth Avenue, and they were going to close that window during the convention in Madison Square Garden.” (Heck, pp. 22) And he describes some of PTH campaign work during that period. During the interview Charley retrieved a copy of a letter written in 2004 to friends and allies regarding Potter’s Field and co-founder Lewis Haggins being buried there as a John Doe and he shares a photo of himself and Jean Rice at a Canners campaign protest. Charley brought a lot of knowledge about Potters Field to PTH. “Bill Phillips, a person that I had slept beside in hallways and doorways and banks—he died, and we held the funeral service for him, and he is now buried in Calvary Cemetery in Queens. And so that was just one person. I had several other—we buried several other people that we knew on the street through the Midnight Run.” (Heck, pp. 25) He reflects on what that work meant to him, “I was not doing just simply nothing… Like waiting for the world to come to me, like the world owed me something—that I was now doing myself. I was doing something.” (Heck, pp. 26) And he describes some of the meetings held during the Potters Field campaign, and the PTH members and faith leaders who were involved and shares that “For people that have never been forced to live on the street—the uninitiated… They really don’t have a conception of the life of a homeless person. And for them to devise all these programs and charities is helpful to a degree, but it doesn’t satisfy the sense of accomplishment. It doesn’t really give a person a sense of accomplishment—of doing something, and that’s what I feel is vastly insufficient in helping people on the street.” (Heck, pp. 28)

PTH Organizing Methodology

Being Welcoming

Representation

Education

Leadership

Resistance Relationships

Collective Resistance

Justice

External Context

Individual Resistance

Race

The System

Burials

Family

Abuse

Vietnam War

Drafted

Dioxin

Street

Shelter

Police

Quality of Life violations

Rights

Cans

Bathhouses

Programs

Abandoned

Belittlement

Inhumane

Media

Church

Midnight Run

NYPD

Women

Rights

Lawsuit

Cam Ranh Bay, Vietnam

Saigon, Vietnam

Connecticut

Ft. Dix, New Jersey

Ft. Lewis, Washington

Oakland, California

Garrison, New York

Ossining, New York,

Greymoor New York

Dobbs Ferry, New York

New York City boroughs and neighborhoods:

Long Island City, Queens

Midtown Manhattan

East Harlem, Manhattan

Lower East Side, Manhattan

Hart Island, Bronx

Civil Rights

EAU [Emergency Assistance Unit]

Potters Field

Canners

Organizational Development

[00:00:00] Greetings, Introductions.

[00:00:47] My association with Picture the Homeless deals with the Potter’s Field Campaign and, earlier work with the Midnight Run in burials of persons that we knew that lived on the street. Because of that experience, I jumped at the opportunity to become chairman of the Potter’s Field Campaign.

[00:01:51] Born in Middletown, Connecticut, a college town, and I have a high school diploma and two years of college with no degree. I will be seventy years old next July.

[00:02:58] I have mixed feelings concerning my family. My mother died when I was eighteen years old, and my father was this cruel, abusive criminal, mother was a college graduate of the University of Oklahoma, and my father dropped out of school.

[00:04:03] All through my early years growing up, going through elementary school, and going through high school—not once, not even once did my father purchase for me a pair of shoes. He was constantly in argument, threatening the board of education to take me out of school so that I could go to work with him! He was a trapper and a hunter.

[00:05:42] When I was sixteen years old, I told him I wanted to go to church. He hit me on the side of the head, told me to change my clothes and go with him to stick bait on his lobster boat.

[00:06:11] I have two brothers. When my mother died, I was eighteen years old. One brother, Guy Heck was born mentally retarded, when my mother died, my father was no help in taking care of him. I have a second brother, Joseph. He was sixteen when my mother died and Guy was fourteen, I was eighteen.

[00:07:56] At eighteen, I went off to the war in Vietnam. My brother Joseph skipped third grade, and when he graduated from high school, he was the valedictorian. His first project while he was still in high school was to convert a mechanical power plant into a hydrodynamic power plant. He worked in atomic energy, and he built a diagnostic analyzer for GM’s 1980 Cadillac.

[00:09:21] My brother was at the top of his class. I struggled through high school with a barely passing grade. When my brother finished high school, industry and government took him right away, my little brother Guy was mentally retarded, left at home and when the state found out about the conditions that he had to live with the state took him from us.

[00:10:45] I remember when we found your brother Joseph? We got his number and called him, he loves you very much, and he told me that your all’s childhood was really hard and that your dad was hardest on you. There are no happy memories from childhood to share.

[00:12:01] After I turned eighteen, registered with the Selective Service board, six months later inducted into the US Army in New Haven, Connecticut. Others from my hometown were drafted, they put about twenty of us into this room, and they recited to us the oath that we had to take and we raised our hand, and there was about seven or eight out of the twenty that refused.

[00:14:17] While I was being inducted, there was protest, this was Dr. Spock’s New Haven, I could hear outside the building, the protests going on. I can remember the noise, the Department of Defense was starving to get people signed up. I was indifferent. I would hear various reasons for an excuse not to go into the military.

[00:15:51] My paternal grandfather was a German naval officer in World War I, and my maternal grandfather was in the US Army as a finance officer. I wasn’t really against the Vietnam War, and I wasn’t really for the Vietnam War. I mean, I thought whatever they asked me to do, I will do it.

[00:16:50] At Fort Dix I went into this platoon, and for three days, they were pushing me towards the infantry, after they discovered that I had a high school diploma, they sent me to a different platoon where they gave us training in what officers should know about the military. I graduated from basic training, and they sent me to telephone lineman school.

[00:21:06] There were eighty-eight of us in the telephone lineman school, and eight-five of us got sent to Vietnam, so I got forty-five days leave, and at the end of the forty-five days, I reported to Fort Lewis, in the State of Washington, spent three days there and took the flight to Cam Ranh Bay in Vietnam. I was eighteen years old.

[00:22:45] It was one hundred-five degrees when I got off the plane in Cam Ranh Bay, you could see the steam coming off of the recent puddles of rain, on the airport runway. In the middle of the night, we were attacked by rockets, they canceled the next day’s school instruction and sent us to our permanent duty station, right away.

[00:24:52] We landed at the air force base and then next door is this huge military installation called Long Binh, I spent about a week in replacement company until I got my position and my permanent duty station where I remained for the next fourteen months.

[00:26:00] I’m told I’m going to be sent north, it would all be considered classified information, but now, it’s fifty years later, I can talk about these things. I remember flying over the country of Vietnam and the ground was covered in water-filled craters. It looked like every inch of the ground had a hole in it.

[00:27:23] I got to my permanent duty station, as we were landing the camp was getting hit with rockets and mortars. The heaviest action that I saw in Vietnam was on my very first day in my duty station! After a while, the guns would go off, and we would just continue sleeping, we became inured to the firing of the canons.

[00:29:35] I laugh at these social workers, “Well, you could go to the senior citizen center and socialize.” I said, “There’s no socializing at this level! Millionaires socialize—in penthouses of expensive hotels.

[00:30:42] We would be paving streets, what they use for pavement is kind of like an oily tar, and we would work with that stuff. In that tar of course, they put the dioxin. I’m suffering from is effects from dioxin poisoning, that’s my exposure to the Agent Orange. It came in fifty-five-gallon oil drums, and got its name from the armed stripe around the outside of the oil drum.

[00:32:48] There was no sense of training, they didn’t even know what the hazards were of the use of that stuff. It wasn’t until like ten years after using it that they found out that this was the cause of these diseases, I was there for fourteen months.

[00:33:15] I came back to the States towards the end of the Vietnam War, I had gained the rank of sergeant E-5 and was discharged from the military in Oakland, California. After the first few months in Vietnam, I made a deal and spent an additional two months in combat. When I got back, I was immediately discharged from the service, and left the United States Army in with a big pile of money.

[00:36:09] I was getting harassed by lifetime military soldiers that “It was better for me if I remained in the military instead of just immediately discharging after my enlistment.” I really didn’t want any part of it! My deal was to do my two-year enlistment and then just have nothing else to do with the military.

[00:38:34] I thought of myself as an industrious person, I thought of the military as top heavy. I got to be a sergeant, and what disgusted me the most about it was I would be in the communication center, and there just wasn’t enough work for me to do!

[00:40:10] After the war, the first year, I did absolutely nothing, I signed up for [un]employment insurance and lived off the state for a year. I started working as a garbage man in Waterbury, Connecticut. The job was miserable, and I was living by myself. I was paying one hundred-fifty dollars a month for a five-room house, it was beautiful!

[00:43:24] At various times as a teenager, I was involved in the home improvement industry, building houses… I worked on Katharine Hepburn’s house when I was a teenager. That was one of my jobs anyway.

[00:44:31] During that younger period my favorite kind of work was in home construction, I wanted to learn things, the surveying tools, the operation of bulldozers and backhoes and cranes and I took the initial stages in it but then I got called into the military! So that ended that.

[00:46:05] When you were younger and you wanted to go to church, your dad hit you on the side of the head and made you go work? Yeah. He poked out my right eye. I’m blind in my right eye. It didn’t affect going into the military, the examiners told me because I scored so high on the educational part, and they needed men so badly that they would waiver my eyesight requirement.

[00:47:39] When I returned from Vietnam, I had this fiery, consuming rage. I was walking around as some kind of mixed-up kid! After a couple of years as a garbage man in Waterbury, this rage consumed me, and I couldn’t seem to hold on to any meaningful job or meaningful employment.

[00:50:06] This rage was driving me over the years until, ultimately I was spending endless hours in barrooms, and ended up on The Bowery in New York City. I tried some of the government programs that they have for alcoholism, joining self-help groups like Alcoholics Anonymous, and they just weren’t helping me.

[00:51:12] The Holy Name Society has a program in a monastery in Garrison, New York. They have control of this mountain in Garrison, like a religious center. It’s called the Universal Center of Atonement, or something like that.

[00:52:25] For three weeks, I went up there in the middle of winter, shoveling snow off this mountain. I was on the landscaping crew, then I left the monastery, and started working in Ossining, New York for North American Van Lines. I only lasted there about two years. I went back to Connecticut and started working back in the home building industry.

[00:54:07] I had no family! My father was never around! My brother was taken by the government, he’s a rocket scientist working for the US Navy. He was never around. He was always so very busy, and my little brother was mentally retarded, he was taken from us by the state! My grandfather’s generation, they all died by that time! I have no one!

[00:54:52] Ended up on The Bowery, I was a student at LaGuardia, but I failed at that. I couldn’t keep up with that. I was always hanging around in barrooms! It was the initial stages of becoming homeless, in a very small park; I would spend a night or two sleeping out on the street. This was in 1976.

[00:55:39] I was in a shelter, “Oh, this is a great new thing we’ve got! A great new program that’s going to help everyone.” I went to this shelter run by Salvation Army in Long Island City. This was a shelter that was going to help all of Vietnam Veterans that were living on the street, one of the most disgusting experiences I ever had in my whole life.

[00:57:01] I had this puny, little nail file, and upon entering the shelter, you go through security and empty your pockets of everything and pass through the inspection before you can get in the shelter. I’m going in and out of the place for about two weeks and then one night, some security guard said, “You cannot come in here with this.”

[00:58:42] I says, “Look man, I’ve been in here for two weeks already and nobody said I couldn’t bring it in here, but you on your very first day on the job says I can’t come in here with this.” They got the supervisor, and the supervisor said, I could. I guess I didn’t need their shelter because I went out in the middle of the night in a blinding snowstorm, walked across the bridge over the East River, back to my spot where I had been sleeping on the street for a number of years already.

[01:00:13] Today, December 12th, 1996. I was arrested for trespassing inside a bank that I had a live bank account in. I think I was sleeping on a floor, that winter was called “the winter of sixteen storms.” The police told me that, “It was a violation of the Quality of Life.”

[01:01:42] I’ve had various scrapes with the law for various offenses, and I tell the police nothing! I went before the judge, and the judge gave me an ACD [Adjournment in Contemplation of Dismissal]. If I didn’t commit any more crime for six months, that this incident would be erased from my record. So I accepted the deal.

[01:02:42] Then I took the police department and the City of New York to court, and won. I’m a homeless man living on the street! I won a case against the City of New York and the police department! They awarded me eight thousand dollars. It took the city comptroller seven years to sign the check.

[01:04:04] I knew what my rights were, it’s one of my basic instincts as an American citizen! It’s just like what Lewis [Haggins] said. It’s just like what Lewis said when he was woken up in the shelter at three a.m.

[01:04:47] In 1986, I was living in an abandoned office trailer, collecting bottles and cans in the streets of Midtown, talking with other people that lived on the street, I found out about this thing called the Midnight Run. I called and they said “Okay, we’ll come down there, and we distribute clothes and food to people that live on the street, and we’ll stop by in the middle of the night.”

[01:06:17] I was in my abandoned office trailer, and one Friday night they show up! Joe Gilmore, had a little Volkswagen Beetle, and he would fill the thing up with what food and clothes he had and come out on a Friday night and distribute these things to the homeless in Grand Central station, by himself!

[01:08:23] Joe Gilmore ignited this spark that grew into what is now the Midnight Run. Westchester County is supposed to be in the top-five, wealthiest counties in the whole United States. I said, “this is a great thing. These people were helping out the homeless in New York City.” I went to some of their meetings, and they would organize a roster of what churches would come out on specific nights of the week.

[01:10:05] During this time, living in the abandoned trailer, I thought Joe Gilmore was a bit crazy to travel fifty miles in the middle of the night to someone he had never met to hand him a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. But it kind of goes like this, the mad scientist develops a robot for the betterment of humankind, and everything is going fine and great, and everybody’s happy and then the robot takes a mind of its own and starts terrorizing everybody that had anything to do with its creation.

[01:13:50] When he first started coming, I says, “Aren’t there homeless people in Westchester County? Why do you have to travel fifty miles to perform this humanitarian deed?” He explained why he was doing this, those people in Westchester County have big jobs on Wall Street, and they would travel through Grand Central station and see all these homeless, all over the station.

[01:15:45] The Midnight Run enlarged itself into an organization of about fifty churches and was big enough to apply for accreditation with the New York State Department of Charitable Services. It was beyond the scope of a volunteer effort. Now, you would think a person like me would be the perfect example of someone that would be hired in a permanent position but that did not happen.

[01:18:19] I was selected as their first chairman of the board of directors. They kept me in the dark, like they were growing mushrooms, was on the board for about six months, still homeless during that time, picking up cans and bottles in the street, it was too dirty a job for me to handle anymore. I did it for several years.

[01:19:29] Not getting any VA benefits, the whole week long, I would schedule rounds to different churches in Manhattan Island, Holy Apostles on Thursdays, and there would be St. James’ Church on Tuesdays, St. Agnes on Saturdays.

[01:20:28] People offered to help me get housing, they said, “Oh, you have to take a psychological evaluation.” I refused a psychological evaluation. There’s nothing wrong with me! It’s the same thing with the Veterans Administration. If you’re a homeless person and you want help from the Veterans Administration, you have to put yourself under the care of a psychiatrist. There’s got to be something wrong with you, to get that money.

[01:22:14] I joined Picture the Homeless in 2004, after more than twenty years of living in the street. I heard that there was a bunch of people on 116th Street in East Harlem that were doing something about police brutality and harassment and unlawful arrest and so I took the time to investigate for myself what this was all about. That’s when I joined Picture the Homeless.

[01:23:28] Constantly harassed by the police while homeless over those twenty years, I was arrested one time and went before the judge, and I refused to accept the ACD, talking with the attorney and going back and forth in front of the judge three or four times until the judge finally says, “Take him to the psychiatric ward in Bellevue Hospital.” After two weeks in Bellevue the doctors couldn’t find anything wrong with me, so they had to release me, there must be several dozens of times that I had altercations with the police.

[01:25:20] First impressions of 116th Street, the Picture the Homeless office, I was a little skeptical, in twenty years on the streets, I went to the Coalition for the Homeless. I got tired of their bullshit, they give you a ticket to go into one of the city-run shelter armories, to sleep on a cot. I suppose there are many thousands of homeless that accept that kind of belittlement.

[01:26:31] When the Coalition for the Homeless started, they were given office space as a charity inside the building on Central Park West, the Ethical Culture Society. From that tiny little space in the Ethical Culture Society, they finally rented office space from the Protestant Bureau of Charities on 22nd Street and Park Avenue.

[01:27:16] That’s when I got involved with the Coalition for Homeless. They had a meeting every month that was supposed to involve the public, the media, and the staff at the Coalition for the Homeless. It went on okay for a little while but then it degraded into something awful, then from 22nd Street and Park Avenue, they got their office where they are now, I have absolutely nothing to do with the Coalition for the Homeless.

[01:28:16] When I was living on the streets in the 1970’s and early 1980’s, I kept a change of clothes inside a locker in Penn Station and I would take my showers in the Allen Street Bathhouse on the Lower East Side. Nobody living on the streets today can remember washing up and bathing in the restrooms of the East Side Airlines Terminal. It’s not even there anymore—it’s a big forty-story building of condominiums, but there’s nothing there for the homeless!

[01:29:18] I remember thinking, “Are these people really for real?” This is 2004, I was asked to participate in a protest against Mayor Bloomberg’s five-year plan to get rid of all the homeless because his plan did not involve the people that actually lived on the streets. The only person that came over and talked to us while we were protesting was David Dinkins. The next protest we had was during the 2004 Republican National Convention. They were going to close the window in the Post Office that handles all the indigent person during the convention in Madison Square Garden.

[01:32:50] Coming to the office, between those two protests, I was a little bit amazed at what was going on, I found out that the group was getting the major portion of their funding from North Star [Fund]. I was with the Midnight Run, then a volunteer organization. North Star gave the Midnight Run funding for one year, and then they cut us off after one year.

[01:34:33] The way that women were getting treated by the city was inhumane. Picture the Homeless was getting involved in was bringing the city to task about the conditions that people had to live with and their children and sending their children to school, and all the problems that a homeless woman would have with children living in those women’s shelters.

[01:36:09] There was a civil rights meeting, a meeting about housing, and they had a shelter committee, we had protests in front of abandoned buildings, I remember one time, we went out to a church in Jamaica, Queens and asked them for funding.

[01:37:31] Motivation to stay involved all these years, PTH co-founders, Lewis Haggins and Anthony Williams, describes his initial involvement of the Potters Field campaign, reads from a letter addressed to potential faith allies about the nascent Potter’s Field campaign.

[01:40:07] [Continues reading from the letter] “Now, five years later Lewis Haggins, one of the two original founding members died anonymously, sleeping on the subway at night. Today, his body is among the eight-hundred-thousand dead in Potter’s Field, Hart’s Island, Bronx. We, the remaining members, feel that because of this great achievement in helping to develop citizenship and other humanitarian efforts, makes him worthy of something better than the city cemetery.

[01:41:02] [Continues reading from the letter] Because of his death, Picture the Homeless is convening a forum to discuss the issues surrounding Potter’s Field, Hart’s Island. The issues relevant are public access, a dignified burial, common, restive worship areas, and a continuous discussion about how we can improve these problems. We would like to invite you to a meeting at our office on October thirteenth at nine-thirty a.m.. Please share this invitation with any of your colleagues that may be interested.

[01:42:02] [Lewis] The letter is signed, “Charley Heck, Leader, Civil Rights Committee”, cc Lynn Lewis, and it’s our letterhead, from 116th Street. Charley, it’s pretty amazing to me that you’ve saved this all these years. You wrote this letter and that fourteen years later, you could go to your other table and pull this off with a clipboard and also a photo.

[01:42:57] The photo is of one of our protests in front of a grocery store, protesting the inability of canners to cash in our empty cans and bottles, the law says that canners were entitled to cash in two-hundred-forty pieces, the photo is of Jean Rice and Charley, Jean Rice’s cousin Eugene had come from the west side, pushing an enormous his shopping cart full of cans.

[01:43:54] Why keep these things all these years? I don't know. The answer is, living on the street, I have an inability to hold on to things. I don't know….

[01:44:38] One of the reasons why we’re doing this project is to document how the organizing work at Picture the Homeless evolved. At the time this letter was written, this was less than a month after we found out that Lewis had been buried in Potter’s Field, as a John Doe.

[01:45:09] [Lewis] I remember you had just started coming to Picture the Homeless that summer, but my memory of you is of you not sitting at the table with everyone, you would sit to the side, and you had a whole bunch of bags.

[01:45:39] [Lewis] And then, when Lewis’s family called me and told me that the police had done a cold case search, and it revealed that he had been buried in Potter’s Field erroneously as a John Doe, we mentioned this in the civil rights meeting, and that was the first time I really heard you speak. You stood up and said, “Well, we must go claim his body.” We were all kind of shocked still and didn’t even know what to do.

[01:46:23] I had earlier experiences working with Joe Gilmore, we interned people, in fact, a close friend of mine, Bill Phillips, a person that I had slept beside in hallways and doorways and banks, we held the funeral service for him, and he is now buried in Calvary Cemetery in Queens, we buried several other people that we knew on the street through the Midnight Run.

[01:47:16] [Lewis] You stood up and challenged us, you said, “What kind of people are you? He’s our cofounder and we must go claim his body.” You showed a tremendous amount of leadership. Then here you are, less than a month later, writing letters. What did that time mean to you? [Heck] I was not doing just simply nothing, waiting for the world to come to me, like the world owed me something. I was doing something.

[01:48:55] The early period of the Potter’s Field campaign, dealing with the Department of Corrections, anything we asked of them, they always said no and because of that rejection, we sought out church groups and faith leaders to help us recover Lewis, body.

[01:49:51] Some of the faith leaders that we engaged with, for people that have never been forced to live on the street really don’t have a conception of the life of a homeless person, and for them to devise all these programs and charities is helpful to a degree, but it doesn’t satisfy the sense of accomplishment. That’s what I feel is vastly insufficient in helping people on the street.

[01:51:58] Picture the Homeless members that worked on the Potter’s Field campaign, Owen Rogers, Rachel Brumfield, William Burnett, Jean Rice, there were like two dozen people that worked with us, we actually went out to Potter’s Field. We went out to Hart’s Island. We made a video; it’s called Journey Towards Dignity.

[01:53:23] Meeting Lewis’s family during the Potter’s Field Campaign, it was a wonderful experience. There were eighteen of us, we met with the Commissioner of Corrections in his office. I spoke with the commissioner privately, and he divulged to me that that year, it must have been 2005 there were eight hundred bodies interned in Potter’s Field.

[01:54:46] Still street homeless at the time, going to meetings with commissioners, it was a wonderful opportunity.

Charley asks to end the interview at this time, “I’m getting a little tired of this right now. I don’t want to go anymore—on this day. Can I cut it short now?”

Lewis: [00:00:28] Okay. I’m going to adjust the sound levels. Here we go. Charley, just talk, and I’m going to adjust the sound levels. You want to say something, so I get to hear how your voice sounds?

Heck: [00:00:28] Well, how far back are we going to go? I mean in the beginning, what happened?

Lewis: We’re going to go back. I’m going to ask you about where you’re from and things that are important to you in terms of your early childhood or things that influenced you and talk about you going to Vietnam and that you’re a veteran because that really does relate to everything you went through afterwards, and you’re going to tell me stories that you think are important. Okay? All right. We’re already recording, but we’re just testing, so now, we’re going to get started, okay?

Heck: Yes.

Lewis: [00:00:00] All right. So, it’s December 12, 2018, and I’m Lynn Lewis with the Picture the Homeless Oral History Project here in the home of Charley Heck, a longtime leader of Picture the Homeless. Hi, Charley.

Heck: Hi.

Lewis: How are you?

Heck: Well, I’m feeling okay today.

Lewis: I’m glad. I’m happy to see you.

Lewis: Charley, we’re going to start off the interview by maybe getting to know you a little better by talking about where you’re from... Could you tell me a little bit about where you’re from?

Heck: [00:00:47] Well, my association with Picture the Homeless deals with the Potter’s Field Campaign and—effectively, through my earlier work with Joe Gilmore and the Midnight Run in burials of persons that we knew that lived on the street. I had extensive experience dealing with the matter of internment. So, because of that experience, I jumped at the opportunity to become chairman of the Potter’s Field Campaign.

Heck: [00:01:51] I’m from Connecticut. I was born in Middletown, Connecticut—a college town. The number one—the number one industry in that town is education. The school is Wesleyan University and I have a high school diploma. I have two years of college with no degree. I am now sixty-nine years old and will be seventy years old next July.

Lewis: What was Middletown like when you were growing up? What was your family life like?

Heck: [00:02:58] Well… I had—I have mixed feelings concerning my family. My mother died when I was eighteen years old, and my father was this cruel, abusive criminal. I don’t know... My mother was a college graduate, she graduated from the University of Oklahoma, and my father dropped out of school—he felt that spending so much time in school was for babies—and that he was going to be a grown-up man.

Heck: [00:04:03] And if you read in the Bible… You put your efforts all towards work, it’s considered debt. [Long Pause] All through my early years growing up, going through elementary school, and going through high school—not once, not even once did my father purchase for me a pair of shoes. He was constantly in argument and adverse—threatening the board of education to take me out of school so that I could go to work with him!

Lewis: What kind of work did he do?

Heck: [00:05:19] My father was a trapper and a hunter—occupations that had very little to do with public society.

Lewis: Did you go hunting with him?

Heck: [00:05:42] When I was sixteen years old, I told him I wanted to go to church. He hit me on the side of the head, told me I had to change my clothes and go with him to stick bait on his lobster boat.

Lewis: I know you’ve got two brothers, is that right?

Heck: [00:06:11] I have two brothers.

Lewis: Mm-Hmmmm.

Heck: When my mother died, I was eighteen years old. My first brother I’m going to talk about is Guy Heck. Guy Heck was born mentally retarded and when my mother died, my father was no help in taking care of him.

Lewis: Hmmmm. Were you the oldest?

Heck: [00:07:00] Myself I’m eighteen years old—I have a second brother, Joseph. He was sixteen when my mother died—and Guy was fourteen, so. So, my father had a relationship with us… You know if something had to be done in the home or at home, and we needed my father to do something, he would wait until the very last minute to do something about it and then, ultimately the very last minute would come, and then he would just simply forget about it.

Heck: [00:07:56] So… Eighteen years old, I went off to the war in Vietnam. My brother Joseph was a—well, I’ll talk a little about my brother Joseph. My brother Joseph skipped third grade, and when he graduated from high school, he was a year ahead of his peer group and he was still the valedictorian of his class. And one of—and his first project while he was still in high school was to convert a mechanical power plant into a hydrodynamic power plant. And he went on—he worked in atomic energy... He built the Three Mile Island power plant in Pennsylvania, and some of his other earlier projects—he built a diagnostic analyzer for the General Motors’1980 Cadillac.

Heck: [00:09:21] So my brother was at the top of his class. I myself, I struggled through high school with a barely passing grade. Now, so—right away, when my brother finished high school, industry and government took him right away. And so, my little brother Guy was mentally retarded, left at home and when the state found out about the conditions that he had to live with… I remember talking to the counselor, and the counselor said, “We found him alone in the house eating peanut butter and jelly sandwiches.” So the state took him from us.

Lewis: [00:10:45] Well, that all sounds really hard. I remember when we found your brother Joseph? Remember we

Heck: Yeah.

Lewis: got his number and I called him, and, you know—he loves you very much, and he told me that your all’s childhood was really hard and that your dad was hardest on you. So, I’m sure that… Thank you for sharing all that because I’m sure those are painful memories. And, do you have any happy memories from when you were a kid that you want to share now before we move on?

[Long Pause]

Heck: [00:11:36] No.

Lewis: All righty, so... You… Did you—

Heck: In the future—if I think of something in the future, I’ll bring it up.

Lewis: All right, great. So you went into the army, was it?

Heck: Yes.

Lewis: Went into the service? And were you drafted, or you volunteered?

Heck: [00:12:01] Well… I went down to the Selective Service board. Soon after I turned eighteen, I went and registered with the Selective Service board, and six months later I was inducted into the US Army in New Haven, Connecticut.

Lewis: What was that like?

Heck: Well, it was a day of examinations and interviews and then in the middle of the night, they put us on a bus and sent us to Fort Dix, New Jersey.

Lewis: Did you know anybody else there on the bus?

Heck: You know, there was like, five persons from my hometown that were drafted at this… It was 1969—April 22, 1969, and the Department of Defense was starving to get recruits. And when I took the oath—I mean they put about twenty of us into this room, and they recited to us the oath that we had to take and we raised our hand, and there was about seven or eight out of the twenty that refused, and so they just took those seven or eight people out of the room.

Heck: [00:14:17] And… Even while I was being inducted, there was protest. I mean this was New—this was Dr. Spock’s New Haven, and even while I was being interviewed and inducted I could hear outside the building, the protests going on.

Lewis: What were they saying?

Heck: [Long pause] Well, the details of them, I can’t really remember them—but I can remember the noise… And the Department of Defense was starving to get people signed up. I was indifferent. I didn’t—I didn’t… I mean, I heard, I mean… You know, I had a few months after I got my letter until the actual date of my entering the service. I mean, like—people would—people that I knew, they says, “You know—could hide in Canada... You can say you’re living under extreme hardship and that serving in the military would cause hardship…” And all that, and I would hear various reasons for an excuse not to go into the military.

Heck: [00:15:51] But, my father’s father—my paternal grandfather, he was a German naval officer in World War I, and my mother’s father—my maternal grandfather, he was in the US Army as a finance officer and so I was indifferent. I mean, I wasn’t really against the Vietnam War, and I wasn’t really for the Vietnam War. I mean, I thought whatever they asked me to do, I will do it and so I submitted myself to the military draft.

Lewis: [00:16:50] And—after Fort Dix… What was Fort Dix like when you got there?

Heck: Well, [long pause] they had… I went into this platoon, and for three days, they were pushing me to—pushing me towards the infantry. But after they discovered that I had a high school diploma, they sent me to a different platoon and I had in that platoon, I had this lax drill sergeant. He was from the Philippines and compared to the drill sergeant I had in the first platoon; this guy was like absolu—like nothing! The guy that was leading me into the infantry platoon, he was—he was on top of us almost every minute of the day, and I guess I was fortunate that I only had to spend one week in that platoon.

Lewis: [00:18:52] And so, in the second platoon that you went into, what were they training you to do?

Heck: They were giving us training in like what officers should know about the military. And—although we did… We went on ten-mile marches, and we did—we had physical training every morning for forty-five minutes and learned—learned how to care for different weapons and the use of different weapons. [Long pause] And then I graduated from basic training, and they sent me to school, and school was just across the street—telephone lineman school across the street. So, what we did on that day was just walk across the street and we were in our occupational training. So, I was in training to be a telephone lineman.

Lewis: And how was that for you?

Heck: I didn’t like it. I hated climbing up those telephone poles with the gaffs on the sides of my legs.

Lewis: [00:21:06] And then from Fort Dix, what happened?

Heck: In Fort Dix, I got forty-five days leave, and at the end of the forty-five days—in that telephone lineman school, there were eight-five of us in the—no, there were eighty-eight of us in the telephone lineman school, and eight-five of us got sent to Vietnam, out of the eighty-eight. And so, I got forty-five days leave, and at the end of the forty-five days, I reported to Saint—let’s see—Fort Lewis, the State of Washington and I spent three days there and took the flight to Cam Ranh Bay in Vietnam.

Lewis: And you were eighteen years old?

Heck: Yes, I was eighteen years old.

Lewis: When you were on your forty-five-day leave, what did—did you go home?

Heck: Yes, I spent the forty-days at home in Connecticut.

Lewis: [00:22:45] What was it like for you when you got off the plane in Cam Ranh Bay?

Heck: It was one hundred-five degrees—steaming hot. And you could really see—you could see the steam coming off of the recent puddles of rain, on the airport runway.

Lewis: What was running through your mind? Do you remember?

Heck: Well… They were going to give us classroom instruction. They sent us to the barracks at night and then in the middle of the night, we were attacked by rockets. And so, in the middle of the night, they canceled the next day’s school instruction and sent us to our permanent duty station, right away. I can remember—I can remember the guy interviewing me, and he says, “In your papers here, it says you’re going to be… You’re lucky, you’re going to be one of the lucky ones. You’re going to get sent south, where most of the fighting now is in the north.” So, in the middle of the night, they put us on a cargo plane, and I went to Cam Ranh Bay just out of Saigon. It was eighty-five degrees in the middle of the night. I can remember that.

Lewis: And y’all were staying in cots, like bunk beds?

Heck: [00:24:52] Well… [Long pause] I got to Long Binh... See camp… There’s the air force base—so we landed at the air force base and then next door is this huge military installation called Long Binh. And they put us in a section that’s called [Ninetieth] Replacement [Battalion] company. And so, I spent about a week in replacement company until they—until I got my position and my permanent duty station where I remained for the next fourteen months.

Lewis: And where was your permanent duty station?

Heck: [00:26:00] Okay, so... I’m in the Replacement company and so now, I’m told I’m going to be sent north... And at that time, it would all be considered classified information, but now, it’s fifty years later—I can talk about these things. [Long pause] I remember flying over—I remember flying over the country of Vietnam and looking out the window, and the ground was covered in water-filled craters. It looked like every inch of the ground had a hole in it. So there really was a war going on there.

Heck: [00:27:23] I got to my permanent duty station, and immediately—as we were landing in the base camp of Quan Loi, the camp was getting hit with rockets and mortars. And so, that was really my heaviest action that I saw in Vietnam was on my very first day in my duty station! That’s—I was attached to a headquarters company, and [long pause] the function of that unit was long-range artillery. We had cannons there that would shoot—projectiles twenty—and hit targets twenty miles away! I was in the headquarters company, and there was three firing—there was three firing units that actually did the—that actually had the guns. Right next to us was Alpha Company and, you know—the first few days that we’re there, the guns would go off in the middle of the night, and they would wake us up! And then after a while, we would be sleeping away and the guns would go off, and we would just continue on sleeping away! It became—we became inured—we became inured to the firing of the canons.

Lewis: [00:29:35] Were there—did you make friends? Were there friends that you—friendships made? At the time, did you-all have opportunities to socialize with each other?

Heck: Well, you know—what I think about socializing… You know, people socialize in the penthouse of the St. Pierre Hotel. I mean, at this level—there’s no socializing at this level... Why would you? Pssssssh… I laugh at these social workers, “Well, you could go to the senior citizen center and socialize.” I said, “There’s no socializing at this level! Millionaires socialize—in penthouses of expensive hotels. There’s no—what do you mean? Might be a fistfight now and then! There’s no socializing.”

Lewis: [00:30:42] When… I remember one time, we were looking at your medical records, and you had been exposed to Agent Orange?

Heck: Yes.

Lewis: So how did that happen?

Heck: Okay… So, I’m in the telephone—Signal Corps, and after we—there was very little work that we did with the telephones. And—so, most of our work was—there’s a term in the military. It’s called “detail”. And so, we were considered “detail men”, and we would be paving streets. Now, what they use for pavement is not asphalt. It was this really oily stuff. It was kind of like an oily tar, and we would work with that stuff. In that tar of course, they put the dioxin—what I’m suffering from is effects from dioxin poisoning, and they use that stuff to kill the weeds... I mean, they would send us out as detail men to kill the weeds in the barbed wire with this stuff. And that was—that’s my exposure to the Agent Orange. Agent Orange used to come in fifty-five-gallon oil drums, and it had—it’s got its name from the armed stripe around the outside of the oil drum.

Lewis: So, you had to handle this?

Heck: Yes.

Lewis: [00:32:48] And did they train you?

Heck: There was no sense of training about—they didn’t even know what the hazards were of the use of that stuff. It wasn’t until like ten years after using it that they found out that this was the cause of these diseases!

Lewis: And so, you were there for fourteen months?

Heck: Yes.

Lewis: [00:33:15] And then you came back to the States, and where did you go?

Heck: Well… I was [long pause] Well, let’s see. It was like getting towards the end of the Vietnam War, and I left Vietnam on November 22, 1970… And I had gained the rank of sergeant E-5… And I was ultimately, discharged from the military in Oakland, California. [Long pause]

Lewis: Are you seeing something? You’ve got your eyes closed, are you picturing it in your mind?

Heck: Yeah, well… After the first few months, I made a deal. After the first few months in Vietnam, I made a deal that if I volunteered to remain in combat for two months after my initial first year, that the final five years [months] of my two-year enlistment would be erased when I returned to the United States. And so, I signed up for that program, and I spent an additional two months in combat. And when I got back to the United States, I was immediately discharged from the service, and I was paid those—I got paid for those five months of early discharge from the military. So, I left the United States Army in Oakland, California, with a big pile of money.

Lewis: [00:36:09] What were those last two months of combat like?

Heck: Okay… Well… I attained the rank of sergeant, so I was no longer—I was no longer—it was imprudent for me to associate with the other enlisted men. [Long pause] That now, my associating with the military was exclusively with staff members.

Lewis: And what was—what was that like? What was your association with them like—what—could you tell me a story about…?

Heck: Well I was constantly—I was constantly… I was getting harassed by these lifetime military soldiers that I, “It was better for me if I remained in the military instead of just immediately discharging after my enlistment...” And… I was always at odds with the—with these other staff members. I really didn’t want any part of it! I mean, I—my deal was to do my two-year enlistment and then just have nothing else to do with the military.

Lewis: [00:38:34] Could you describe for me why you didn’t want to reenlist? Why did you want out?

Heck: I thought of myself as an industrious person, and I looked at the… I thought of the military as—as top heavy. If you could understand what I’m talking about—it would be top heavy… They’re all—I got to be a sergeant, I had—I had very little things to do except… What disgusted me the most about it was I would be in the communication center, and it would be like the whole day long, I’ll be just leaning up against the wall thinking about things to do. I mean, there just wasn’t enough work for me to do! I mean I felt—I felt as myself, as an industrious person.

Lewis: Did your feelings about the war, did they evolve in any way after you got over to Vietnam?

Heck: [00:40:10] Well… [Long pause] The first year, I did absolutely nothing. The first year, I did absolutely nothing until I got a job as a garbage man in Waterbury, Connecticut.

Lewis: So, when you went back to Connecticut, did you go to your hometown or where did you go?

Heck: Yes. [Long pause] But as far as doing work or engaging in an occupation, I did absolutely nothing for a year.

Lewis: [00:41:33] And you had—you had a big chunk of money?

Heck: Yeah… Well, I signed up for [un]employment insurance and so I lived off the state for a year. And it was getting near the end of my term, so I decided to go to work… I started working as a garbage man in Waterbury, Connecticut.

Lewis: What was that like?

Heck: Oh, that was miserable—had to be at work at four thirty in the morning.

Lewis: And were you living in Waterbury?

Heck: Yes, I was.

Lewis: Who were you living with?

Heck: I was by myself.

Lewis: Was that the first time you lived by yourself?

Heck: Well, during my first year, I lived in a house in Cornfield Point. I remember now—it was called South Cove Road in Cornfield Point in Old Saybrook, Connecticut.

Lewis: And you lived in a house?

Heck: Yes, I did.

Lewis: By yourself?

Heck: I was paying one hundred-fifty dollars a month for a five-room house.

Lewis: What was that like?

Heck: Oh, it’s beautiful!

Lewis: [00:43:24] Did you move from that house to Waterbury?

Heck: Yes, I did because the kind of work that I wanted to be involved with—there was nothing in the locality of Old Saybrook that—anything there attracted me for work.

Lewis: What kind of work did you want to do?

Heck: Well [long pause] at various times as a teenager, I was involved in the home improvement industry.

Lewis: What do you mean?

Heck: That we were building houses… I worked on Katharine Hepburn’s house when I was a teenager. That was one of my jobs anyway.

Lewis: [00:44:31] During that—the younger period of your life, what was your favorite kind of work that you did?

Heck: Well… It was in home construction, and I wanted to learn things—the surveying tools, the operation of bulldozers and backhoes and cranes and…

Lewis: Mm-Hmmmmm. So, did you get to do that?

Heck: Well… I took the—I took the initial stages in it but then, you know—I got called into the military! And so that ended that.

Lewis: [00:45:39] What was Waterbury like when you lived there?

Heck: Oh… Well… I guess it was just like any other job that a person has.

Lewis: [00:46:05] You had mentioned when you were younger and you wanted to go to church, and your dad hit you on the side of the head that made you go work…

Heck: Yeah. He poked out my right eye.

Lewis: Poked it out?

Heck: I’m blind in my right eye. I cannot see from… This side of my face is nothing. I have vision only in this side of my face.

Lewis: From your dad?

Heck: Yes.

Lewis: [00:46:31] Did that—that didn’t affect you going into the military?

Heck: No. Because the—the examiners told me because I scored so high on the educational part… My score was one-twenty-eight out of one-twenty-eight, in five categories, and there were six categories in the examination. But they told me that I had such a high score in the educational part and that they needed bodies—they needed men so badly that they would waiver my eyesight requirement.

Lewis: That’s amazing. That’s amazing.

Lewis: [00:47:39] So, when you were younger, did you go to church?

Heck: Yes, I did… My mother and my grandmother—her mother, and my father’s mother dragged me to church every Sunday.

Lewis: Since—when I met you, I—I got to know pretty quickly that you were a person of very deep religious faith. Where does that come from?

Heck: Okay... Now, what happened with me when I returned from Vietnam—I had this rage. I had this fiery, consuming rage. It was—I was in this stage of confusion like I was walking around as some kind of mixed-up kid! And this completion of the military service just… It just fortified this burning rage and it—what was driving me crazy. And… So, after a couple of years as a garbage man in Waterbury, this rage consumed me, and I couldn’t seem to hold on to any meaningful job or meaningful employment.

Heck: [00:50:06] I mean it was—I mean it—it was, this rage was driving me over the years until, ultimately I was spending endless hours in barrooms, and ultimately I ended up on The Bowery in New York City. And so [long pause] I tried some of the government programs that they have for alcoholism… And joining self-help groups like Alcoholics Anonymous, and… They just weren’t helping me.

Heck: [00:51:12] And so, the Holy Name Society… The Holy Name Society has a program—you get sent to a monastery in Garrison, New York. It’s run by the Franciscan Friars of Atonement at Greymoor, in Garrison, New York. And they got this monastery—it’s on this... They have control of this whole, big mountain in Garrison, New York, and it’s all like a religious center. It’s called the Universal—the Universal Center of Atonement, or something like that.

Heck: [00:52:25] And so for three weeks, I went up there in the middle of winter, shoveling snow—shoveling snow off this mountain in the middle of winter. I was on the landscaping crew and so for three weeks, I was up there—after the three weeks, I left the monastery, and I started working in Ossining, New York for North American Van Lines... But… I only lasted there about two years. [Long pause] I went back to Connecticut and started working back in —as what I did as a teenager—in the home building industry. And I was working with a guy, and we were rebuilding palatial mansions… Houses costing millions of dollars and his... He would advertise we were building custom-built homes on both sides of the beautiful banks of the Connecticut River.

Lewis: [00:54:07] Did you—were you in touch with your family at the time, after the war?

Heck: I have no family! My father was never around! My brother was taken by the government—in education, and ultimately… He’s a missile scientist. Now he’s a rocket scientist working for the US Navy. He was never around. He was always so very busy, and my little brother was mentally retarded, he was taken from us by the state! My grandfather’s generation, they all died by that time! I have no one!

Lewis: [00:54:52] When you—you said that you ended up on The Bowery… What brought you to New York?

Heck: I was a student at LaGuardia Airport [pauses] but I failed at that. I couldn’t keep up with that. I was always hanging around in barrooms!

Lewis: Did you become homeless then?

Heck: You know, it was the first initial stages. You know in a very small park; I would spend the night or two sleeping out on the street. This was in 1976.

Lewis: [00:55:39] Did you get help from any agencies at the time, or how did you end up…

Heck: Those agencies, they’re—I think they’re disgusting!

Lewis: Tell me why.

Heck: You know, I was in a shelter they were making, “Oh, this is a great new thing we’ve got! This is a great new thing coming out now! A great new program that’s going to help everyone.” And I—you know, so I latched on. I started hearing that I… I went to this shelter. It was run by Salvation Army on Borden Avenue, in Long Island City. This was a shelter now that was going to help all of Vietnam Veterans that were living on the street… [Long pause] One of the most disgusting experiences I ever had in my whole life.

Lewis: [00:57:01] What was it about it that bothers you so much?

Heck: I had this puny, little nail file, and I would go through the security—upon entering the shelter, you’ve got to go through security and empty your pockets of everything you’ve got and pass through the inspection before you can get in the shelter. So, I’m doing this! I’ve got this puny little nail file. I’m going in and out of the place, displaying what I’ve got on my persons and for about two weeks... So, I’m going in and out of the place—two weeks and then one night, I come in about eight-thirty P.M., and I empty my pockets, and some security guard—some guy that I had never saw before—I think it was his very first day on the job—said, “You cannot come in here with this.” It was a puny, little nail file. I think I paid thirty-nine cents for it, in the drugstore.

Heck: [00:58:42] So, I says, “Look man—I’m coming in and out of this place... I’ve been in here for two weeks already... I’ve taken this thing in and out of here, already. Nobody said anything. Nobody said I couldn’t bring it in here, but you on your very first day on the job says I can’t come in here with this.” So, they went, and they got the supervisor, and the supervisor said, “He can come in here with the nail file.” [Long pause] I went to my locker, got all my clothes, got everything that I had, and I walked across the Queensboro Bridge in a snowstorm. I guess I didn’t need their shelter because I went out in the middle of the night in a blinding snowstorm, walked across the bridge over the East River—back to my spot where I had been sleeping on the street for a number of years already. I guess I didn’t need their shelters.

Lewis: Where was your spot that you stayed?

Heck: It was in an alleyway next to St. James’ Church on Madison Avenue and 75th Street.

Lewis: [01:00:13] You mentioned that today, December twelfth

Heck: Yes.

Lewis: in the nineties? You…

Heck: December twelfth—

Lewis: tell me that story.

Heck: 1996.

Lewis: What happened on that day?

Heck: I was arrested for trespassing inside a bank... A bank that I had a live bank account in.

Lewis: And what were you doing when you got arrested in that?

Heck: As I remember, I think I was sleeping on a floor.

Lewis: Why would you have gone in there to sleep?

Heck: Because it was like a—that winter was called “the winter of sixteen storms.”

Lewis: And so, tell me the story of what happened when—how did the police treat you? What did they say?

Heck: [Long pause] They told me that, “It was a violation of the Quality of Life.”

Lewis: What did you do? What did you say?

Heck: [01:01:42] Well, you know, I’ve had various scrapes with the law for various offenses, and I tell the police nothing! And, so I went through the process, and I went before the judge, and the judge gave me an ACD [Adjournment in Contemplation of Dismissal]. If I—he would release me from custody, and if I didn’t commit any more crime for six months, that this incident would be erased from my record. So I accepted the deal.

Lewis: And then that happened?

Heck: [01:02:42] Then what happened? I took the police department and the City of New York to court.

Lewis: And on what grounds did you take them to court?

Heck: I don’t know. I can’ re—I really don’t remember the specific… The specific way that it went on… I really, you know—that was in 1996.

Lewis: That’s okay. So—

Heck: I took them to court.

Lewis: And what happened?

Heck: I won the case.

Lewis: And what did you win?

Heck: I’m a homeless man living on the street! I won a case against the City of New York and the police department! They awarded me eight thousand dollars… But! It took the city comptroller seven years to sign the check.

Lewis: [01:04:04] Oh… [Sighs] How did you know what your rights were so—to… So that you could file a case?

Heck: It’s one of my basic instincts as an American citizen! It’s just like what Lewis [Haggins] said. It’s just like what Lewis said when he was woken up in the shelter at three a.m., just like what he just told us now, on the recording.

Lewis: [01:04:47] You mentioned Joe Gilmore and the Midnight Run, and would you tell me a little bit about what that

Heck: Okay.

Lewis: about that?

Heck: I was collecting cans and bottles. This was 1986. I was living in an abandoned office trailer on Twelfth Avenue and 30th Street, and I was collecting bottles and cans in the streets of Midtown. And… So, talking with other people that lived on the street, I found out about this thing called the Midnight Run. And… So, I called him up, and I got a hold of somebody on the telephone, and they says, “Okay, we’ll come down there, and we distribute clothes and food to people that live on the street, and we’ll stop by in the middle of the night.” They come by... It’s called the Midnight Run, and they operate in the middle of the night.

Heck: [01:06:17] So I was in my abandoned office trailer, and one Friday night they show up! Joe Gilmore and this woman called Annie Quintana… Actually, Annie Quintana is the person that started the Midnight Run and Joe Gilmore started the Midnight Run because the church members—in his church in Dobbs Ferry, New York, were coming to him and complaining about the sight of all these homeless people in Grand Central station. And Joe says, “Well, you know, we can do something.” So, Joe Gilmore, I think had this puny, little Volkswagen Beetle, and he would fill the thing up with what food and clothes he had… You know, it’s only a small, little compact car—and he would come out on a Friday night and distribute these things to the homeless in Grand Central station, by himself! And from there, he searched out other church organizations in Westchester County, and they formed this organization called the Consortium [on Homelessness]. And from the Consortium grew what today is called the Midnight Run.

Lewis: [01:08:23] And then—were you—you were on the board of the Midnight Run?

Heck: Yes. Well—because I had lived in Westchester County years earlier, in Ossining, New York, I was like, familiar with the area. And like, I knew some of the people around Ossining and Dobbs Ferry, and this spark, this—he ignited this spark. Joe Gilmore ignited this spark that grew into the—what is now the Midnight Run. And I says, “Well, you know—this sounds like a great thing for people to do to help out—people from…” Westchester County is supposed to be in the top-five, wealthiest counties in the whole United States. And I said, you know “I thought about this, and this is a great thing. These people were helping out the homeless in New York City.” And so, I went to—I went to some of their Consortium meetings, and during the Consortium meetings, they would organize a roster of what churches would come out on what specific nights of the week.

Lewis: [01:10:05] And this was during the time you were living in the abandoned trailer?

Heck: Yes.

Lewis: So, they started coming around to the trailer where you were. How did you meet them? How did you end up going up to Westchester and working with them, being on their board?

Heck: [Long pause] Okay… Well, I have to have a break from this.

Lewis: Okay.

[INTERRUPTION] Adjusting mic, “Okay, there you go, here let’s watch your hands.”

Lewis: [01:10:50] All right. So, tell me the story of how you met Joe and actually started talking to him and getting to know him as a—you know?

Heck: Well… I thought he was a bit crazy. I thought Joe Gilmore was a bit crazy… To travel fifty miles in the middle of the night to someone he had never met to hand him a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. [Long pause] But [long pause] it kind of goes like this. The mad scientist develops a robot for the betterment of humankind, and everything is going fine and great, and everybody’s happy about this new invention and then, suddenly, the robot takes a mind of its own and starts terrorizing everybody that had anything to do with its creation.

Lewis: Are you saying Joe Gilmore is the mad scientist?

Heck: [Long pauses] That’s my perspective.

Lewis: [01:13:50] When he first started coming after you made the phone call, and he started coming—was it him that would come in his Beetle to your trailer?

Heck: Yes.

Lewis: Did you talk? Did you try to talk? Did he talk you up?

Heck: Yes. I says, “Aren’t there homeless people in Westchester County? [pause] Why do you have to travel fifty miles to perform this humanitarian deed?”

Lewis: And what was his answer?

Heck: Well, he explained to me why he—why he was doing this… And it was because the church—he has—those people in Westchester County have big jobs on Wall Street, and they would travel through Grand Central station. They would see all these homeless, all over the station, I mean, like dozens and dozens of homeless. This was way back in the 1980’s. This is way back in the 1980’s when CBS television took Mayor Ed Koch to court over the homeless problem. And CBS found out that New York City was just a little bit too big for CBS to handle the problem. This is way back when.

Lewis: So you ended…

Heck: This is like thirty and forty years ago.

Lewis: So, you ended up—did you move up to Dobbs Ferry and get involved with the Midnight Run?

Heck: [01:15:45] Okay. [Pauses] So now, the Midnight Run enlarged itself into an organization of about fifty churches... And so now, it was big enough to apply for accreditation with the New York State Department of Charitable Services. So… They needed a board of directors. They needed a primary corporate sponsor. They needed a full-time staff. It was beyond the scope of a volunteer effort. [Long pause] Now, you would think a person like me would be the perfect example of someone that would be hired in a permanent position… No, that did not happen. It was no longer in the control of Reverend Joe Gilmore, but now was under the direction… Of their primary corporate sponsor.

Lewis: Hmmmmm.

Lewis: [01:18:19] So, you were on the board of the Midnight Run?

Heck: Yes.

Lewis: And—?

Heck: I was selected as their first chairman of the board of directors.

Lewis: What was that like?

Heck: They kept me in the dark, like they were growing mushrooms.

Lewis: How long were on the board?

Heck: About six months.

Lewis: And were you homeless still, during that time?

Heck: Yes.

Lewis: [01:18:53] Were you… When did you go to Madison and Seventy-Fourth. Was that after the trailer?

Heck: What?

Lewis: When you were staying out on the street?

Heck: Yeah, well… You know, picking up cans and bottles in the street, it just—it just got simply… Like it was too dirty a job for me to handle anymore. I mean, I did it for several years, but, I don't know… I grew out of it.

Lewis: [01:19:29] How did you make a living, after that?

Heck: I didn’t.

Lewis: Were you getting any VA benefits?

Heck: No.

Lewis: Where would you eat?

Heck: [Pauses] My whole week long, I would schedule rounds to different churches in Manhattan Island... Like, it would be Holy Apostles on Thursdays, and there would be St. James’ Church on Tuesdays… And there would be St. Agnes on Saturdays.

Lewis: [01:20:28] And you were in the writers group at Holy Apostles for some time, weren’t you?

Heck: Yes.

Lewis: What was that like?

Heck: Yes, I was in a writer—God, I can’t remember. I don't know... That was such a small part of what I did—it didn’t last very long. I would—I don’t know, I wrote a couple of things, tried creative writing for a while but—

Lewis: [01:21:01] During all those years, did anybody offer to try to help you get housing?

Heck: Oh, those people, they’re disgusting.

Lewis: So how did you meet Picture the Homeless—?

Heck: you know… They come to me, and they said, “Oh, you have to take a psychological evaluation.” I refused a psychological evaluation. There’s nothing wrong with me! [Long pause] It’s the same thing with the Veterans Administration. If you’re a homeless person and you want help from the Veterans Administration, you have to put yourself under the care of a psychiatrist. There’s no other way for a homeless person to get help. That is the one, only way—submit to psychological and psychiatric examinations and care! There’s got to be something wrong with you, to get that money.

Lewis: [01:22:14] Tell me the story of how you first met Picture the Homeless.

Heck: Okay. In—let’s see... That was—I joined Picture the Homeless in 2004. This is—2004 is like after more than twenty years of already living in the street. I heard that there was a bunch of people on 116th Street in East Harlem that were doing something about police brutality and harassment and unlawful arrest and so I took the time to investigate for myself what this was all about. And that’s when I joined Picture the Homeless.

Lewis: [01:23:28] Were you harassed by the police when you were homeless?

Heck: You know, I only just talked about one incident—in 1996. But—you know, through all those twenty years, I mean—it was constantly like that.

Lewis: Do you have—

Heck: I was arrested one time, and I went before the judge… And I refused to accept the ACD. So back and forth, between talking with the attorney and going before the judge and refusing the judge’s offer and going back and talking to the attorney again… I went back and forth in front of the judge about three or four times until the judge finally says, “Take him to the psychiatric ward in Bellevue Hospital.”

Lewis: And then what happened?

Heck: After two weeks in Bellevue Hospital, the doctors couldn’t find anything wrong with me, so they had to release me. That was another incident. So now, I talked about two incidents with the police, but there must be several dozens of times that I had altercations with the police.

Lewis: And so, you heard from other homeless folks about Picture the Homeless on 116?

Heck: Yes.

Lewis: [01:25:20] And—what were your impressions when you first got to 116th Street, to the office?

Heck: Well, I was a little skeptical in the beginning.

Lewis: Mm-Hmmm? How come?

Heck: [Pauses] Because, you know—I went to… You know, in twenty years on the streets, I went on to various—I went to the Coalition for the Homeless. I got tired of their bullshit at the coalition. You know what they do at the coalition? They give you a ticket to go into this—one of the city-run shelter armories, to sleep on a cot. I suppose there are many thousands of homeless that accept that kind of belittlement.

Lewis: And so, what was—

Heck: [01:26:31] You know, when the Coalition for the Homeless started, they didn’t have any office space. They were renting office space—in fact, they didn’t even rent the office space. It was given to them as a charity inside the building on Central Park West, the Ethical Culture Society. And from the Ethical—from that tiny little space in the Ethical Culture Society, they got a—they finally rented office space from the Protestant Bureau of Charities on 22nd Street and Park Avenue.

Heck: [01:27:16] And that’s when I got involved with the Coalition for Homeless. I used to go to… They had a meeting every month, and that was supposed to involve the public. It was supposed to involve the media. It was supposed to involve the staff at the Coalition for the Homeless. Well, it went on okay for a little while but then it degraded into something awful... And then from 22nd Street and Park Avenue, they got their office on—I think it’s 129 Wall Street, where they are now… And I have absolutely nothing to do with the Coalition for the Homeless.

Lewis: [01:28:16] What is it that you were looking for then? What would—what would have made you stay?

Heck: You know, when I was living on the streets in the 1970’s and early 1980’s, I kept my clothes—I kept a change of clothes inside a locker in Penn Station… And I would take my showers in the Allen Street Bathhouse on the Lower East Side. I mean nobody living on the streets today can remember washing up and bathing in the restrooms of the East Side Airlines Terminal. It’s not even there anymore—it’s a big forty-story building of condominiums, but there’s nothing there for the homeless!

Lewis: [01:29:18] So, what was Picture the Homeless like when you got there even though you were skeptical?

Heck: Well [long pause] I remember thinking to myself, “Are these people really for real?” [Pause] Until I found out a little bit about the organization.

Lewis: [01:29:56] What kind of things did you find out that were important to you?

Heck: Okay. So, this is 2004, and so right away, I got involved and was asked to participate in a protest… So, I went along.

Lewis: What was that protest about?

Heck: We were protesting Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s five-year plan to get rid of all the homeless.

Lewis: And where was the protest?

Heck: We were protesting, because his plan did not involve the people that actually lived on the streets. It was all politicians and big real estate interests.

Lewis: And what did you do in the protest?

Heck: The only person—the only person that came over and talked to us while we were protesting outside the Grand Hyatt Hotel, and that person was David Dinkins. Out of all the politicians in New York City, he was the only one.

Lewis: And what did that mean to you?

Heck: We were—homeless people were just not accepted to be intelligent enough or civilized enough to participate in the halls of government!

Lewis: And so, after the protest, what happened?

Heck: The Republican—the next protest we had was during the 2004 Republican National Convention.

Lewis: And where was that held?