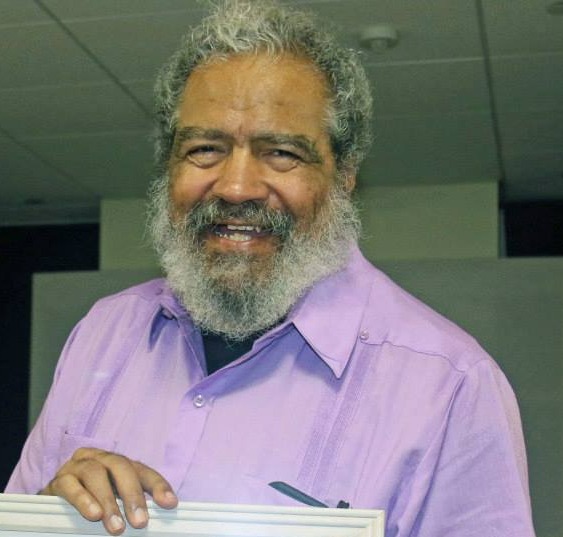

Carlos Chino Garcia

The interview was conducted by Lynn Lewis, on August 21, 2018, with Carlos Chino Garcia in his apartment on the Lower East Side/Loisaida for the Picture the Homeless Oral History Project. In his capacity as Executive Director of CHARAS/El Bohio Cultural and Community Center he was one of the early allies to welcome Lewis Haggins and Anthony Williams, co-founders of Picture the Homeless (PTH) into movement. This interview covers his early childhood and adulthood as an organizer and his reflections on meeting Lewis and Anthony just after the founding of PTH.

Chino was born in Puerto Rico and lived there until his fifth birthday, when he came to New York, joining his parents in 1951 and first living in East Harlem with extended family. Afterwards they moved to Chelsea, “about altogether there were five, six, seven, and we were living in Chelsea in a one-bedroom apartment. But somehow as kids, we enjoyed living there. Our backyard was the Chelsea Hotel when we moved to Chelsea.” (Garcia, pp. 3) His siblings had joined them by this point, and he describes shining shoes as a child, to help out his family here and in Puerto Rico and describes always seeing himself as an immigrant and having a lot in common with other immigrants from South America. He describes the conditions in Puerto Rico that led to a lot of families migrating to the U.S. at that time and the many ways that his parents founds ways to make a living, from factory work to vending. As children, he and his siblings sold newspapers along the docks that lined the west side of Manhattan at that time and on the way home picked up bottles for the deposit.

He also shares going to the movies as a child, in English and in Spanish and going to clubs and theaters. When they moved to the Lower East Side when he was twelve, there were Russian and Polish movies, in addition to ones in Chinese. He also recalls when he first moved to East Harlem enjoying gospel music and after moving to Chelsea travelling back to East Harlem and shopping in La Marqueta. “Pero he still would go to La Marqueta for specialties. Like that supermarket didn’t sell stuff to make pasteles, you know, the plantain leaf and things that. They didn’t sell anything like that. So, he will go La Marqueta still to get specialties.” (Garcia, pp. 9) And he would continue to go to Puerto Rico for holidays and over the summer and shares several stories in his interview. “I had a lot of cousins that I’m very close to and I’m still close to, males and female. I’m one of the few that are very close to my female cousins because I never have that mentality of the macho.” (Garcia, pp. 10) Chino also describes the housing conditions where his family lived, no indoor water, outdoor latrines, and dirt floors as well as the close attachments he formed with his extended family in Puerto Rico.

He describes the Lower East Side, “Man, it’s unbelievable. First of all, what I used to be fascinated about is all the fucking languages, the Jews, the eastern European, Russian, Polish, and I made friends in all those communities. I mean it was really beat up. The residential—I mean the tenement areas. Remember, we moved into the projects, and we were comfortable there. What I liked about the projects is that in between all the buildings there were parks and sitting areas and that kind of stuff. Pero, the majority of the time, I used to hang out in the tenement areas because I used to like it for more... It was mysterious, and it was really heavy ghetto.” (Garcia, pp. 13) They called themselves Nuyorquino and he describes some of the bands he used to listen and dance to. He also describes the gangs, generally comprised of different ethnic groups, and says that among the Puerto Ricans there were differences between those who had migrated before WWII and those who had recently arrived and didn’t speak English but that in general they supported one another.

He recalls that the first time he got involved with politics, “A lot of the Puerto Rican communities supported him. So therefore, in different stores and different locations there was being— preparation for campaigning, leaflets, getting that kind of active, distributing, talk to people. And then, what do you call it? We also helped with the Cuban—raising money for the Cuban Revolution. The Puerto Rican community used to throw parties, and the Latino community in general, too, used to throw parties and raise money to send to Cuba. And basically, that was the beginning of my interest in politics.” (Garcia, pp. 16) He describes going to meetings of Puerto Rican Independentistas, as well as Socialists and Communists, but didn’t identify with a political party.

At age twelve he joined a gang for protection and his parents sent him back to Puerto Rico. When he returned to New York in 1964, the Johnson administration had started the Real Great Society, “there were social workers and all kinds of people coming down, truant officers, and trying to offer us… A lot of us felt we could do the same thing you’re doing, so therefore, we could do it our self. We could put together programs. We could put together… I mean if we put together a hundred people to beat up on some other group, we could also put a hundred people to do other things.” And describes organizing workshops and activities and working with Father Pat Maloney who ran a Catholic center for youth. A member of Chino’s group participated in a youth forum on PBS and that brought them additional supporters and at some point CHARAS shared space with the Black Panther Party in the Christodora House which was vacant when they took it over, “it’s not like when we took over El Bohio, they immediately started giving services. And this time, since we had the experience of the Christodora building, we didn’t allow no bullshit. Because sometimes these people go into meetings, and they start talking this and—you know? People give some of those nuts leadership and then it becomes a nightmare. When we took over El Bohio, we didn’t let anybody throw us off. Immediately, we confronted people that we felt was all crap and no action.” (Garcia, pp. 19)

He also describes the overall conditions in the neighborhood during the ‘70’s as fires set by landlords, burning all over, “It looked like Berlin, during World War II.” (Garcia, pp. 20) And the housing struggles he became involved in including tenant organizing, restoring vacant buildings including be a part of starting the Sweat Equity movement and he shares some of the challenges organizing these types of projects. “Well, neighborhood workshops were discussed and then little by little, people volunteered, and you could see… You know, in that building, you had to physically work hard. You just cannot come around and talk and smoke a joint and things like that. You could smoke a joint, pero you’ve got to work too. I mean basically, it was a… And the way we chose them is the more you participate, the more you have clout, you know, to get an apartment.” (Garcia, pp. 21)

Chino reflects on meeting Lewis Haggins, who was attending AA meetings at CHARAS, and Lewis’ interest in “, helping in housing, helping in, what do you call it, medical and food with homeless people. And basically… One day, he brought Anthony in.” (Garcia, pp. 22) And they said that they wished that they could form an organization, they become homeless advocates. So, one of us asked them, “Exactly what do you mean by that?” I think Anthony was the one that explained more than Louie exactly. Lewis said a few words, but Anthony had a stronger opinion, I think. They was thinking of doing it on their own somehow, but they didn’t have resources and things like that. So, I told them, “Well, you know, resources are all around us. So, you see that empty desk? You guys use that with the telephone.” (Garcia, pp. 22) He shares why it was important to him to offer support, “I had respect because I saw him coming to meetings. And when you’re a brother that’s down-and-out, and you want to develop yourself and clean yourself up, it shows that you’re serious. So basically, you know, I’ve dealt with a lot of groups throughout the city and the country with a lot of people that basically they have an idea, and you have to encourage them quickly to take—to become serious with that idea.” (Garcia, pp. 23) Because at the time they weren’t a group yet, but from his experience working with people he felt they were sincere. He also shares why he introduced Lynn Lewis to Lewis and Anthony, and that he's learned how to put people together.

PTH Organizing Methodology

Being Welcoming

Representation

Education

Leadership

Resistance Relationships

Collective Resistance

Justice

External Context

Individual Resistance

Race

The System

Migration

Family

Immigrants

Work

Neighborhood

Recycling

Politics

Music

Black

Salsa

Tenements

Projects

Gangs

Poor

Survival

Struggle

Programs

Jails

Empty Buildings

Squatting

El Bohio

Movement

Fires

Sweat Equity

Respect

Spirit

Shelter

Puerto Rican

Do-it-yourself

Housing

Landlords

Volunteers

The Buen Consejo area of Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico

New York City boroughs and neighborhoods:

El Barrio/East Harlem, Manhattan

Chelsea, Manhattan

Lower East Side, Manhattan

Organizational Development

Movement Building

[00:00:00] Introductions

[00:01:03] Born in Puerto Rico, lived there until his fifth birthday, parents had immigrated to New York City, he came to join them in 1951. Parents came right after World War II, and considered the move temporary, always planning on returning to Puerto Rico, which they did.

[00:02:45] First lived in El Barrio, East Harlem, New York City where many other family members were already living. Then moved to the Chelsea neighborhood where they lived in a one-bedroom apartment behind the Chelsea Hotel, his parents and their five children.

[00:04:14] Shined shoes as a child, sometimes in front of the Chelsea Hotel, developed relationships with folks in the Chelsea Hotel from childhood through the Vietnam War era, first beatniks and then hippies where were living there, including Abbie Hoffman and Emmett Grogan.

[00:05:31] They all had to help make money for the family in New York and in Puerto Rico. Family helped them and other family members when they came from Puerto Rico, it was done for love. His great aunt Ita cared for him after his parents left Puerto Rico for New York, and he was very close to her.

[00:08:02] Parents left Puerto Rico for work and money, like other immigrants. Some Puerto Ricans do not identify as immigrants, but as migrants. He identifies as an immigrant, connected to other Latinos who were just like him in terms of language, culture and way of life.

[00:11:07] His parents were successful with work, and helped many others, they figured out how to make money, working in a factory or hotel but also vending.

[00:14:02] As children, he and his siblings sold newspapers, and used baby carriages to transport them, selling them along the docks on Manhattan’s west side from Twenty-Third Street down to the World Trade Center area. After the papers were sold, they picked up empty bottles and earn ten cents for each bottle, a tremendous amount of money at that time.

[00:17:02] Comparison of the cost of living between those times and today. They sold the empty bottles to a man who washed them in a basement and made homemade rum, called Cañita or Pitorro, which was cheaper than what alcohol cost in a store.

[00:19:45] His sister did other types of work, many people worked in the Garment Center. The family was successful at hustling, giving money to the church, sending some to Puerto Rico and also going to the movies.

[00:21:23] His parents went out of their way to send their children to the movies every Saturday so they could have time to themselves.

[00:22:59] Description of favorite movies, he separated liking John Wayne movies from John Wayne’s politics, they also saw a lot of movies in Spanish, and went to Latin shows on the Lower East Side, Chelsea, and the Bronx. After they moved to the Lower East Side when he was twelve, they saw karate movies in Chinatown, and Russian and Polish films, without subtitles, and it was fun.

[00:27:35] El Barrio was mostly Latino; the majority were Puerto Rican. He went to an African American church across the street from his grandmothers apartment, drawn to the gospel music and impressed with the rhythm in the reverends voice. After the family moved to Chelsea, his father would return to El Barrio to buy food in La Marqueta.

[00:33:46] His family obtained a larger apartment on the Lower East Side, a three bedroom, the five brothers shared a room, sometimes with cousins that would stay over, including those who would come from Puerto Rico.

[00:35:51] He returned to Puerto Rico whenever he had the chance, remaining very close with family there. Unlike many of his male cousins, he developed close relationships with his female cousins who were in the majority in his grandmother’s house.

[00:42:37] At fifteen, sixteen he was able to get into clubs to dance salsa because he was always tall. An older cousin loaned him money to buy an expensive suit, his aunt washed it, ruining it his aunt counselled him to not value material things over family relationships.

[00:52:15] On the Lower East Side many languages were spoken, people were from different countries, he made friends in all of those communities. The housing, the tenement areas, were really beat up, his family lived in public housing projects.

[00:54:02] The interview is interrupted, description of the terms Nuyorquino and Nuyorican, different salsa bands from the neighborhoods, the Lower East Side and East Harlem.

[00:57:40] The Lower East Side in the late fifties had different gangs of Blacks, Puerto Rican, Jewish and eastern European and Puerto Ricans. There were differences among Puerto Ricans who came before World War II and who were more Americanized and those who had just come from the island and didn’t speak English well but they would support one another.

[01:00:23] Involved with the presidential campaign of John F. Kennedy, he had a lot of Puerto Rican support, and he supported the Cuban Revolution which was also supported by the Puerto Rican and other Latino communities, also attended meetings of the Puerto Rican independentista, socialista and communist parties.

[01:02:44] He was a member of a gang from about twelve years of age, around the mid-fifties. Initially, for protection because if anybody messed with Puerto Ricans, they would confront them as a group. Later, gangs became involved in crime and drugs. His parents sent him to Puerto Rico for over a year to change his mentality.

[01:05:06] Returning to New York, a lot of others in the group were tired of gang life/crime. President Johnson had started the Great Society and social workers and others were in the community offering programs. People felt that could create programs based on skills they had developed in gangs and began organizing. A priest gave them space for a few years.

[01:08:44] Still teenagers, they rented an apartment on 6th street for their headquarters. PBS held a youth forum and invited them to participate. A guy named Turban who had been in prison represented them, and afterwards a high school teacher in Harlem came to visit with his wife and offered to help.

[01:11:35] His work has been featured in several articles; he doesn’t remember all of them. Two are Down These Mean Streets and Bandana Republic. His daughter Taina told him that they were reading a book in her book club that mentioned him, he’s in a lot of articles, not only him but the group.

[01:12:39] The Christodora House had been one of the first a settlement houses. It was moved because a lot of services were leaving the community because they felt the need in the Lower East Side was decreasing. The Christodora was turned over the Department of Social Services and was a Welfare Center for a time and then empty, during the '60s. They approached the city and requested that it be used for social programs. They refused.

[01:15:28] During the early '60s, their group was called the Real Great Society. With other groups, including the Black Panther Party, they took over the Christodora. Folks started squatting, and the neighborhood was upset. When they took over El Bohio [next door to the Christodora], in the late '70s, early '80s, the main group was CHARAS and Adopt-A-Building. They immediately started offering services to the community and were more demanding that everyone work, and not just talk.

[01:19:52] The housing conditions in the Lower East Side, fires were burning all over the place, especially between Avenue A and D, as well as south of Houston St., landlords were setting them for insurance purposes.

[01:21:00] Started doing tenant organizing in the '60s, around '65. When the fires started they had to figure out a way to restore some of the building. In 1971, CHARAS, Adopt-A-Building and a few other groups, started talking about renovating one of those buildings with volunteers and future tenants and started the Sweat Equity movement.

[01:22:45] Description of the Sweat Equity Project, sponsored by Adopt-A-Building with support from CHARAS, neighborhood poets such as Bimbo Rivas and Jorge Blandon would come and sing and entertain the volunteers. The building is still for low-income people.

[01:24:52] Process of selecting who would live in the building, sweat equity hours, each hour worked was valued at ten dollars and everyone had to do physical work. Fast forward to when he met the co-founders of Picture the Homeless.

[01:26:51] Lewis [Haggins] used to attend AA meetings at CHARAS/El Bohio. During breaks he would talk with him, and he would read the literature around the building. Many AA members didn’t get involved in other issues, but Lewis began sharing that he wanted to participate in several things.

[01:28:05] Lewis wanted to help with housing, and other issues. One day he brought Anthony [Williams]. Lewis and Anthony sat down, and talked with Armando Perez, Ken and Tony Arroyo. They wanted to form an organization and become homeless advocates but didn’t have resources. Chino offered them use of the telephone and an empty desk. Lewis went to the AA meetings and was really making an effort to get away from his problem with alcohol.

[01:31:34] He didn’t see Anthony as much; he didn’t attend AA meetings regularly but would stop by. Lewis know Al Sharpton, and they discussed working with Judson Church and Washington Square Church, two churches that he had worked with.

[01:33:14] He had respect for Lewis when he first met him, he saw him coming to meetings and felt he was serious. It’s important to encourage people with ideas, they felt that it was a necessary idea because there wasn’t such a group of homeless people, they weren’t just trying to help themselves, they cared about other people.

[01:35:35] In his lifetime he has dealt with thousands of people, and had a feeling that they were sincere about their idea, and it’s an idea that didn’t exist in the city of homeless people forming their own advocacy group. Seeing Lewis coming to AA every day, he felt that he needed something to put time into, and that was it.

[01:37:22] He had been involved with the housing movement but not necessarily with homeless people. He had seen people in the Bowery sleeping on the sidewalk and had dealt with hobos, homeless people are in a different category, they are the poor of the poor.

[01:39:40] He asked them to meet with [Lynn Lewis] because he remembered that she had been homeless in a shelter, even though that wasn’t the same as the street, and had experience working on housing, he has learned how to put people together in his life.

Lewis: All right. So, today is August 20—what? First? [Laughter] Around there, in 2018. I’m Lynn Lewis, and I’m here with [Carlos] Chino Garcia for the Picture the Homeless Oral History Project. Hi, Chino.

Garcia: [00:00:25] Good afternoon. Always nice to see you.

Lewis: Thank you for lunch.

Garcia: [00:00:31] I’m glad you enjoyed it. It turned out to be… It turned out good. [Laughs]

Lewis: So, this is the first interview that you and I are doing for this project, and I want to ask you, to share some about who you are because who you are, I think, is important to the story of Picture the Homeless. And so, could you tell me where you’re from?

Garcia: [00:01:03] Yeah. I was born in Puerto Rico, and I lived there as a kid all the way to my fifth birthday. My mother and father were already in New York when I came. So—oh, and the place in Puerto Rico I’m from is Buen Consejo, which is a village from Rio Piedras, or—now a neighborhood. Basically, it’s part of the metropolitan area of Puerto Rico, you know?

[00:02:02] And we, I came here in 1951. My parents came here in the—right after World War II when I was born. They came to settle temporarily because, at some point, they wanted to go back to Puerto Rico once they saved enough money. And they accomplished their goal, the did return back to Puerto Rico. But I came to this country in 1951.

[00:02:45] The first neighborhood I lived in was in El Barrio, [East Harlem, New York]. My uncles and grandmother, a lot of other members of my family were living there. And after that, we decided to move to Chelsea, in the West Side, and basically we got an apartment. And when I’m saying we—we’re talking about altogether there were five, six, seven, and we were living in Chelsea in a one-bedroom apartment. But somehow as kids, we enjoyed living there. Our backyard was the Chelsea Hotel when we moved to Chelsea. That’s between Eighth Avenue, and Seventh. Throughout the years, it was nice having a relationship with people from the Chelsea Hotel because it always was a pretty progressive place.

[00:04:14] I remember as a kid, I used to shine shoes… On the corner of Eighth Avenue and Twenty-Third Street. Once in a while, I used to go to in front of the hotel by the restaurant to shine shoes because, basically, a lot of the beatniks, they used to live in the Chelsea Hotel. They didn’t get their shoes shined. It’s very rare. [Laughs] I think only if they had a special occasion, they would come to me and this other shoe shiner from the neighborhood.

[00:04:56] As kids, it was interesting that I developed a relationship with the Chelsea Hotel all the way through the civil—I mean through the Vietnam War system and the hippies… Became there... Instead of the beatniks, it was the hippies who came later, and they were all living in the Chelsea Hotel. Of course, Abbie Hoffman and Emmett Grogan and a whole bunch of those studs used to go there a lot.

[00:05:31] Pero, basically as a kid, you know, I used to try to make a living because as an immigrant family, we all had to help, all the kids, to raise funds not only for us in New York, pero usually, a percentage of it used to go to Puerto Rico. Our grandmother was there and a couple of great-aunts, and we had to help, you know? I remember when my mother and father came to this country, they helped me and my family. They never charged us any money. It was all done for love. So, one of my grand-aunts—we used to call her Ita, actually took care of me for around four years after my mother left to come to the United States. So, I became very close to her throughout my life, you know, because she almost became my mother as soon as I was born in 1946. And I lived with her for almost five years with all her kids. Altogether, she had around nine kids.

Lewis: Were your other brothers and your—you have one sister? Were they all living there, too, with her?

Garcia: [00:07:16] No, they were living in Santurce, [Puerto Rico]. They were my stepbrothers [“half-brothers”] and sister, but they were living in Santurce. I became more associated with them when we all were living in New York. We were very tight all the way through our adult life.

Lewis: Your mother and father, what brought them to New York? Why did they move?

Garcia: [00:08:02] Work, and money. New York… A lot of Puerto Ricans came after the war to live in New York, and mainly, they came here like any other immigrant. You know the Puerto Rican, it’s funny. I use the word immigrant and I always use the word immigrant. Some Puerto Ricans say, “Oh, we’re not immigrant. We’re migrant.” And you know, [Laughs] to me, it was funny because I saw these other Latinos from South America, and they were just like me. They didn’t speak English. [Laughs] I wasn’t different from them. We knew that we were Latinos. So, to me, I always considered myself an immigrant. Migrant worker? You know, that’s a whole different question, but I always felt I was an immigrant because all the immigrants that came from South America, all had the same habits I had, the same ways of life. We think almost the same way, so I really always saw myself as an immigrant, never as a so-called migrant worker.

Lewis: Could you talk about what was happening in Puerto Rico that created this—the conditions where so many Puerto Ricans came to the States after World War II?

Garcia: [00:09:58] Well, it was mainly jobs. You know—I mean jobs. My oldest brothers, they were going to school in Puerto Rico. As kids, when they came to this country, they already knew how to read and write. So therefore, it wasn’t for education because the educational system, at that time, was already in place. Mostly, everybody that came, I remember, they came to work… And we helped each other. You know, when people came to this country from Puerto Rico, mostly everybody moved to the same neighborhood where the village—where the people from the same village used to live, and that was one thing that I remember.

[00:11:07] My mother and father were very successful people with work. I remember my father and mother used to take a lot of those people when they came—you know, because we used to help them, not only as Roman Catholics or as immigrants or as Puerto Ricans, pero just humane. We used to help anybody that needed advice and things like that. My mother and father always have a saying to people, you know, “You know what’s good about this country? That if you cannot find a job, invent one.” [Laughs] And it’s true! My father knew and my mother knew how to do that because they did it. They figured out a way how to make money. I mean, they preferred working in a factory or hotel or something like that. They preferred that, but to be honest with you, there’s always a way how to make a buck, and they knew how to do that. I’m not talking about illegal stuff—simple, simple things like you go and you buy fifty Puerto Rican flags, and you sell them. The flag cost you five cents each, you sell them for twenty-five cents, and that things, you know? That’s the way you tried to survive. And my mother did it with jewelry... You know, at that time, plastic didn’t exist, so there used to be all kinds of other type of jewelry. I used to consider those jewelry very beautiful because I used to deliver them to customers for her and that kind of stuff. Pero, the most important part is that they always felt there’s no reason why you should be down-and-out because there’s a lot of opportunities.

[00:13:16] And like us as kids, as little kids, we used to get up like five in the morning, and we used to go to this newsstand that used to be on Ninth Avenue and… On Ninth Avenue and Twenty-Third Street, and we would buy the_ Daily News_ and—what was the other paper? There is a reason why I’m mentioning this, because the [New York] Post was a more conservative newspaper at that time.

Lewis: The Post?

Garcia: [00:14:02] Yeah... No, no, more liberal newspaper, the newspaper, the Post, which was used to… You know at that time, there used to be like ten news—daily newspapers in New York. The Mirror, Daily News, the_ Post,_ the_ Journal, _and a few more! So therefore, we will go buy... But the one we could sell the faster, usually, I think it was the Daily News—and the Mirror. We will buy a whole bunch of those newspapers for—I think it was three cents each. You know, we used to have those old baby carriages. You know, they didn’t make—they wasn’t made out of aluminum either, [smiles] they were fucking heavy. Pero, you know, those baby carriages, they were like this—they were like a ship, and we filled them up with newspapers. And we’d go to the docks in the river, and we would walk from Twenty-Third Street all the way down to what we know now as the World Trade Center that area there—I forgot the name of the street—pero beyond Christopher Street, you know?

Garcia: [00:15:31] And there were dozens and dozens of ships! I mean, those big cargo ships loading and unloading. And they would buy—the used to give us—we’d buy the newspapers for three cents each, and we used to sell them for five cents. Pero, usually, the dock workers and the merchant marines would give us twenty-five cents—the majority—or ten cents. Very rare they should just give us five cents, “Hey kid!...” You know, and they were very nice people to us. Anyway, so, we’d go all the way down to almost—what is known now as the Battery Park selling newspapers, and that would take us almost an hour and a half to walk that distance. And then on our way back, we used to pick up all the empty Pine bottles and the empty liquor bottles and the wine bottles and bring them back. There used to be a guy on Twenty-Third Street that would pay us ten cents for each bottle. I mean ten cents at that time was a tremendous amount of money, tremendous amount of money.

[00:17:02] For example, at that time, you could buy a slice of pizza and a soda for fifteen cents. Now, a pizza cost almost three dollars and a soda cost almost two dollars, you know? Pero, that’s just to show the differing of economics of different periods. And then, we would give them… We would sell them all those empty bottles. We’d bring back the baby carriage filled with all kinds of bottles, and he was really cool. He will give us our money and then he will go and wash them in the basement of the building where they used to do the rum. They were pretty… You know, homemade run, which is—it used to be called Cañita or Pitorro. It used to be very popular at that time because it was cheap compared to what you would pay in the store. The only problem is that one time in the late fifties, the guy sold a whole bunch of rum for a party—I can’t remember what kind of party it was… And more than, I think, twenty-seven people died. That means he made a mistake with his mix, and it was sad. It was a sad story. It was all over the newspaper, the English and Spanish newspapers. At that time, I think the Puerto Rican, or the Latino newspaper was called El Imparcial and then El Diario came out and then they both joined. So now you, I think when you see _El Diario _in the bottom of the word diario it says Imparcial, you know?

[INTERRUPTION: Chino’s cell phone rings]

Garcia: [00:19:31] Talking about the devil, David. [Smiles] So anyway, so basically… He went out of business; you know what I mean? God bless him.

[00:19:45] Pero, it was an interesting culture because as immigrants, we used to have to work to help the family here and the family in Puerto Rico and—all of us did that. My sister used to do other things with sewing and that kind of stuff. A lot of people, they work in the Garment Center. Remember, I was on Twenty-Second Street. We were on Twenty-Second Street and Tenth Avenue. The Garment Center is only—was only like starting in the—on Thirty-Fourth Street, that all the way through Forty-Second Street was the Garment Center. I mean they were coming all over the place, but that was the center, you know? So basically, we—what do you call it—were very successful as a family, hustling. And of course, you give a little bit to the church, you send some to Puerto Rico to grandma, and you also go to the movies. At that time, the movie—for three movies, you’d pay only twenty-five cents, and a popcorn was five cents inside the movie. Now, I think it’s like five dollars. [Smiles]

Lewis: If you’re lucky.

Garcia: If you’re lucky, right. [Laughs]

Lewis: If you’re lucky. If you have a coupon.

Garcia: [00:21:23] Man, they charge you a lot of money for that damn popcorn now, [smiles] but at that time man, we used to stuff ourselves with popcorn. The other thing is that one of the reasons our parents enjoy—I mean went out of their way on weekends to send us to the movie because that was the only time that we were—that they had for themselves. You know, a one-bedroom apartment, five boys, one girl, and sometimes a couple of cousins. [Laughs] So that’s the only time they had for themselves by sending us to the movies, you know? And they would do that every Saturday. Pero, the reality is that at that time, you will see the movies used to—for twenty-five cents, they used to offer you three movies, and in between each movie, there would be cartoons, you know, or episodes to see. So, therefore, you could stay in the movie that day. We would be there for like [smiles] five hours or six hours, which is the only time that our parents had to have some personal life, you know what I mean? [Smiles] I mean, it’s interesting how that stuff works. But that was the only way they could do it. [Laughs]

Lewis: Do you remember any of your favorite movies when you were at the time in your life?

Garcia: [00:22:59] I used to love the Creature from the Black Lagoon, King Kong, and a few westerns. I can’t remember them, a few westerns. I mean, one other thing that’s funny. I used to like John Wayne, the cowboy, right, pero then as I grew up and became political, I really feel—I still like John Wayne, the cowboy—pero, I didn’t like his politics. [Smiles] So then you had to make a decision of his politics and the cowboy aspect of John Wayne, [laughs] and the same thing with a lot of those people. And remember now, I also come from the Latino culture. So, we used to see a lot of movies in Spanish at that time. The majority of the movies that I saw was fifty percent Spanish movies and maybe fifty percent American movies, you know, English movies basically, and the same thing with music, you know? I mean, we would go see a lot of Latin—not only movies, but Latin shows!

Lewis: Where? What were the clubs that you used to go to?

Garcia: [00:24:36] Oh, there were… El Palladium… There were a few. I can’t remember all of them right now, pero then the theater was the Jefferson Theater.

Lewis: Where was that?

Garcia: [00:24:54] On Fourteenth Street and Third Avenue. Now, it’s some kind of a condominium, and they called the condominium The Jefferson.

Lewis: Oh, wow.

Garcia: Yes, it’s interesting. Then we used to go see rock and roll like the Academy of Music, the Brooklyn Fox. Those are places for live entertainment also, and then El Teatro Puerto Rico that was in the Bronx, and a few other theaters, you know? The Elgin, which is now—I mean it’s in the Chelsea—that used to be Latin movies. And then also as kids, we used to go to Chinatown and watch karate movies as kids. [Laughs] It’s funny, the Puerto Ricans, we would go to the Chinese theater, and we didn’t understand not even one freaking word, [laughs] but we used to love these people chopping each other up with their hands and jumping. I mean, it was really interesting.

[00:26:14] And then, we had… When we moved to the Lower East Side, we had an extra privilege, Russian and Polish movies. There were a few movie houses in the Lower East Side, right? When we moved from Chelsea to the Lower East Side, and that’s when we started seeing Chinese and Russian films, Polish films, you know, eastern European. And we didn’t understand in either of those theatres because—and they didn’t have subtitles, either. [Laughs] So, you had to go enjoy the movie based on action and that kind of stuff. And it was fun! I mean, we used to enjoy that. It was a lot of fun seeing—doing that you know?

Lewis: How old were you when you moved from Chelsea to the Lower East Side?

Garcia: [00:27:15] I moved from Chelsea to the Lower East Side in 1958. So, I was born in forty-six, so I was twelve—

Lewis: Twelve—

Garcia: —years old, you know?

Lewis: I’m sorry. When you lived in El Barrio, what was it like then? What was the neighborhood like then for you as a child?

Garcia: [00:27:35] Oh, El Barrio?! El Barrio was—when we first came to this country, that’s where we went to for around a year. El Barrio was really—first of all, it was mostly all Latinos, Puerto Ricans. There were some Dominicans and some Mexicans, but mainly, the huge majority was Puerto Ricans. And I used to love… Across the street, my grandmother used to live on a Hundred and Third Street between Lexington and Third Avenue.

Lewis: On the hill? By the hill?

Garcia: [00:28:24] No, my aunt used to live on the hill. My grandmother used to live in the street. [Laughs] And I remember sitting by her window, and you hear [hums] pa, papapa, papapa, papapa, pa, all this beautiful gospel music of Black people. Across the street, there was a church _and they—boy, they’re swinging, and those women used to go there all dressed up with a big—ah! And they are—_man, singing, you know? And on hot days, they had to leave the doors open! At that time, they didn’t have shit like air conditioners or fans, so they’ll be—you know? I will walk right into the church and sit in the front by the bleacher, or on the floor. _Oh, I used to love that music! And I loved, you know just… And they used to love me. [Smiles] You know what I mean? And I would sit there moving with the rhythm, not necessarily just dancing, pero moving with the rhythm. Pero, but that was always to me very impressive.

[00:29:36] And my grandmother would sit across the street by the stoop of the building just to make sure I’m okay. But she always—felt—_amazing… My grandmother’s name, they used to call her Doña Porfi… You know amazing, that I used to do that. She always felt something interesting about it, you know. You know what I mean? And she always used to say, [imitates her voice], “Man, ese muchacho le gusta a la musica de los morenos.” [Man, this boy likes the music of the Black people] You know what I mean? Moreno means the Black people. And basically, I used to love… I mean that’s when I also felt I loved music, period. And man, those people they used to really—pero not only their music. When the reverend speaks, I mean those guys [smiles] used to speak with so much—they used to throw like vibration throughout the audience because they really spoke with some beautiful rhythm in their—you know what I mean—in the speech. It wasn’t boring, and I also liked that.

[00:30:55] To be honest with you, I really didn’t understand much of it because remember, I didn’t speak English that well. I started learning English more after—when I was around eight, nine years old in elementary school. I think my English improved more in Chelsea; you know? I used to go to PS 11 [Public School 11, William T Harris School] in Chelsea. That’s the elementary school, and that’s when I started improving my English.

Lewis: When you lived in Chelsea, did y’all go back up to El Barrio like to go to La Marqueta and did you go?

Garcia: Oh yeah!

Lewis: What was that like?

Garcia: [00:31:42] Ah, we used to… For the first few years in Chelsea, my father used to go the Marqueta to do his main shopping, and usually, an older cousin would go and help him. My father was very popular among his nephews, always. He always was very popular, so they would go and help him and then when they get back to the neighborhood, to Chelsea, there would always be food and things like that for everybody to eat.

[00:32:22] Pero, then Twenty-Third Street and Ninth Avenue, [New York], they opened up a really nice supermarket. That’s the first time, I think, I experienced a supermarket like—you know? What do you call one of those new supermarket like A&P? I can’t remember what was the name, but it’s still there. Not the same name, pero the supermarket is still there in Chelsea. Basically, that was more convenient for him. Basically, that became the main food source. Pero he still would go to La Marqueta for specialties. Like that supermarket didn’t sell stuff to make pasteles, you know, the plantain leaf and things that. They didn’t sell anything like that. So, he will go La Marqueta still to get specialties.

Lewis: And then—

Garcia: [00:33:43] They didn’t even sell aguacate I think in that supermarket. [Smiles]

Lewis: No. Now, they’re everywhere.

Garcia: Yeah, at that time.

Lewis: What brought your family—to the Lower East Side?

Garcia: [00:33:46] Oh, we went to Hudson Guild, which is a very famous settlement house in Chelsea, one of the oldest ones. Because remember, seven of us were living a one-bedroom apartment. So, we went to Hudson Guild to see how they could help us get a bigger place. And the lady that helped us—she was really nice—got us an apartment in the Lower East Side, which used to be between Rivington and Stanton Street. No, no, no, no, no. It was between Houston and Rivington, on Columbia Street, here in the Lower East Side.

Lewis: How many bedrooms did that apartment have?

Garcia: [00:34:51] Three. My sister was the lucky one. She got one for herself and then we, the five guys, we all lived in one room. [Smiles] You know what I mean? So, we weren’t too happy about that. Then my mother and father, they had their own. But somehow, you get used to each other when you got—it was four—three bunks—table. And there’s always an extra bed because—cousins. We used to help each other out. Sometimes, somebody will come from Puerto Rico, so they would sleep in the extra bed, you know. Pero, that was really a lot more comfortable for all of us.

Lewis: I remember you telling me that you, out of your brothers and your sister, were the one that always wanted to go back to Puerto Rico like in the summertime and stuff?

Garcia: [00:35:48] No, just me.

Lewis: Right.

Garcia: [00:35:51] My father would ask, “You guys want to go to Puerto Rico and spend time with your family out there?” And usually, like the other brothers would say, “Ah, we don’t want to go out there. There’s a whole bunch of hicks out there, jibaros.” [Laughs] So, I was the only one that always used to say, “I want to spend the summer in Puerto Rico.” So, I spent a lot of time throughout the winter—you know, special holidays. If I had a week, my mother and father would send me to Puerto Rico usually. The only time I never went to Puerto Rico was during the Christmas—what do you call—holidays. Basically, I wanted to spend them with my own parents. But a couple of times I told them, I didn’t mind going for Christmas just to spend—see because in Puerto Rico Christmas is all the way through January seven the celebration, so I would go for part of it, like the Three Kings and that kind of stuff.

Lewis: What was it about—why was it that you wanted to go back? What was it that made you want to go back?

Garcia: [00:37:03] Oh, I always, I remember as a little kid, I used to love to climb, go to the beach, climb palm trees, the trees, and all that stuff. You know, I cut my tongue. I never showed it to you, but I have a big cut in my tongue because I fell from a palm tree. Pero, when I was a little boy when I was like four years old, I used to climb those big, fucking palm trees, and take down coconuts. You’re like a monkey, you know. You’ll be jumping all over those trees. You go through the woods hiking, and you get mangoes and aguacates, I mean, just wild! I always loved that. I used to love doing that.

[00:37:57] And I told you earlier my aunt, which she took care of me from the time that I was born until the time I came to the United States, she—I was very close to her, and I used to like to go and spend it with her, you know? Really, I had a lot of cousins that I’m very close to and I’m still close to, males and female. I’m one of the few that are very close to my female cousins because I never have that mentality of the macho. Like when I was around my cousins as a kid, I always would spend time with the girls. And my other—the male cousins used to tell me, “Ah! Why you spend—waste your time with them?” And things like that. Pero hey! My female cousins man, they were very smart [smiles] and they’re—you know? And we wasn’t—what do you call it?

[00:39:12] Let’s say for example, if—usually in Puerto Rico, the males would have their own conversation during parties and the female. So, I used to go and talk about baseball and sports with my cousins, you know. But then I used to go and hang out with my female cousins, and they usually would socialize around the dining room and the kitchen. And I used to go and hang out with them. And the other thing is I got a lot of food [laughter] while I was doing that. They kept on feeding me, pero I used to go and talk to them about issues and ideas and things like that. You know what I mean? I never really liked that atmosphere of separation like that. I never really was that close.

[00:40:07] And I remember being like that as a little kid because the majority of my cousins in my grandma’s house were women. You know what I mean? There were more females than male, so therefore, I had to develop an association. I decided to do this naturally. It’s not something that _I planned. _But it’s this common feeling. If you got more women, more females in the house, you’re going to play with them too, besides your male cousins. You know what I mean? So basically, that was the case.

[00:40:49] And I think that’s what gave me the strength of… Being close to a lot of women in business and that kind of stuff basically—mainly because of them! There were more females— shit, they outnumbered the guys by three or four in that particular—in my grandma’s house. And a lot of the women, their husband left them early. So, they used to take care of me really, I mean unbelievable with—like a treasure. I mean, they would never let me go to the street with a wrinkle on my shirt, never. At that time, they used to use those coal irons, those irons that you have to put coal to warm it up, you know? And they would say, [imitating them] “Where are you going? You cannot go like that.” No matter how poor we were, because we were poor, they always made sure that I was neat, and they would iron my pants even though I used to hate it. [Smiles] They would iron my pants, always with a crease. And they would iron my… If I come from somewhere where I sit, right? My shirt gets wrinkled. I come to the house, [imitating them] “Take off that shirt.” [Laughter] There was me and this other cousin guy, and they used to treat us like—really—so therefore, I appreciated that.

[00:42:37] One time when I was a teenager, I used to go out dancing, salsa dancing in clubs. I was maybe fifteen, sixteen, but the thing is that I was always tall, you know? And I always had a little mustache on me, just a mustache. And I used to go to those clubs, and they didn’t even ask me for ID. They asked other people for ID. They didn’t even ask me for ID. So anyway, so one time I go to one of my cousins. He was an engineer for the harbor authority, and I told him, “Cous, you know that store where you shop?” Because he used to buy really expensive clothes. And he told me, “Yes, what about it?” I said, “You know the other day, I was—I went by that store, and I saw this beautiful suit,” and he told me, “Yes and why?” [Laughs] “You know that’s an expensive place,” he tells me, and I said, “That’s what I want to talk to you about,” and he go, “What? You want me to get you one?” And I said, “Well, let’s make a deal. Buy me that suit,” I explained to him what it was, “and I will pay you back,” because I used to always work as a kid. “I will pay you back every week so much money.” He told me, “Really? You really want that suit that bad?” And I told him, “Yes.” It was a mohair suit, right?

So, I go over with him to the store, and he gets it for me—you know what—like almost two hundred dollars. At that time, we’re talking about, that’s a fortune, you know? And my cousin buys me this suit, and I mean really without any hesitation or anything like that. He said, “Boy, you’re going to attract a lot of women.” And El Cabron was the nightclub where I used to like to go to, and I used to wear it. A beautiful suit with everything—he got me a clip for the tie, a tie, because he used to dress good, so he wanted me—you know, a handkerchief. So… I kept on paying him, and I paid him until the end.

[00:45:17] Pero, one time I had an argument with one of my aunts, and… She—what do you call it—I mean she was like—of all our aunts, all the kids, men and women always felt that she was like the bitch of all our aunts, you know what I mean? So, I leave. So… I come back... Oh, I was working in a restaurant that night, in an Italian restaurant, and I got out like really late at night. So, when I got out… I got out like one in the morning. So, I go home, and I go… I was so tired, I just went to sleep, you know? So, then in the morning when I got up—you know that houses were all wood and the streets and the floor were all—what do you call that—earth. So, when it rains, it became fucking mud. So anyway, and then you had to go to a latrine outside. There was no indoor water.

[00:46:47] Anyway, so I get up, and I go outside, and I get ready to wash my face. I didn’t feel tired. For some reason, I didn’t feel—even though I went to sleep late, I didn’t feel tired. So, when I’m going go throw water on my face, [laughs] I went, and I said, [mimics himself yelling] “Tia Ita, venga, algo paso.” [Aunt Ita, come, something happened] So, I called the matron, Tia Ita was the oldest of all the aunts. [Laughs] She said, “Your Aunt Xuncha washed your suit, and she’s going to iron it later on.” I go, “Oh my God, mohair you cannot wash.”

Lewis: Tia Xuncha?

Garcia: Yes.

Lewis: I met her.

Garcia: [00:47:45] Yes, you met her. Yes, she was—

Lewis: She was the mean one?

Garcia: [00:47:49] Yeah, yeah. When we were kids. [Smiles] As an adult, she was nice. I mean as an older lady, and I go, “I’m going to kill her!” [Laughs] And I was so angry, and I slammed the door, you know? She comes over, and she said, “What are you angry about?” “She washed my suit. That’s supposed to go to the dry-cleaning. You cannot wash that suit and then you cannot put it under the sun because the fucking sun would bleach it.” It was light blue—I mean dark blue. And my aunt told me, you know, she said, “Don’t be mad at her,” and I said, “What do you mean, don’t be mad at her? You know what she just did?” My aunt said, “Remember you had an argument only a few days ago?” And I go, “Yeah, but what do this have to do with this?” She said, “She was trying to make it up for you, and she thought she was doing you a favor.”

Lewis: Oh, wow.

Garcia: [00:49:03] Wow. You know? I go, “Wow.” You know? So, when my aunt come, I said, “Thank you.” [Laughs] And then I went and told my cousin about it, the one that bought the suit. Which I still hadn’t—I only had paid half of it to him. When I told him the story, he started laughing [laughs] because she’s also his aunt, right? And he told me, “Pero, Tia Ita is right. You know, let’s not make a big deal out of this.” I said, “What am I fucking going to do? I don’t have a suit.” He said, “That’s easy. I’ll get you another one.” He said, “We do the same deal, pero we get another suit.” [Laughs]

[00:49:52] Anyway, that was an interesting story. [laughs] Pero it’s love too. It’s a love situation that takes place among all of us, you know, as a family. It’s love, because for me to be angry at her for material—my aunt was right—it’s not worth it. We all live in the same fucking land. My grandmother’s house was… Around ten bedrooms. Remember I told you, all the women they used to live there? And some of my cousins had kids and their husbands and their boyfriends left them, so they all—we all were living in the same house! You know what I mean? We all, we all… And then next door, it was more of my family, a couple of houses and then… You couldn’t have tension because if you have tension in a small—in a crowded situation like that, it becomes a nightmare among all of—for all of us. And my aunt told me, “Don’t look at it like that. Just look at it as a favor, and when she comes home from work, say thank you to her.” You know, and that aunt was very influential in my life, always, almost like my mother. My mother was her little sister.

Lewis: Now, that’s a great story. That’s a great story as an answer to the question why did you want to go back and visit Puerto Rico. That’s a great—

Garcia: [00:51:48] Well, Yeah, because that is—you know, I used to love it, being there, you know? Every, sometimes, one of my other brothers would come with me, pero they would only do it one—once in five years or something like that. They only would do it once.

Lewis: What was the Lower East Side like when you moved here when you were a kid?

Garcia: [00:52:15] Oh, wow. Man, it’s unbelievable. First of all, what I used to be fascinated about is all the fucking languages, the Jews, the eastern European, Russian, Polish, and I made friends in all those communities. I mean it was really beat up. The residential—I mean the tenement areas. Remember, we moved into the projects, and we were comfortable there. What I liked about the projects is that in between all the buildings there were parks and sitting areas and that kind of stuff. Pero, the majority of the time, I used to hang out in the tenement areas because I used to like it for more... It was mysterious, and it was really heavy ghetto. And basically, what do you call it? I had some cousins of mine who lived in the tenements. Basically, I liked the tenement areas because it was more mysterious and that kind of stuff. Besides having cousins, a lot of the guys that I went to school with, they used to live in the tenements. There were tenements all over, all the way—all the way down to Madison Street, you know, clusters of tenements.

And then to this side here—I’m pointing out to Avenue A and First Avenue—that’s where a lot of the eastern Europeans—

[INTERRUPTION: Chino’s cell phone rings]

Garcia: [00:54:13] I gotta take this. Talks on the phone….

Garcia: [00:55:02] This guy—

Lewis: Who?

Garcia: —is an old friend of mine. His name is William Milan. He put together one of the best orchestras, salsa orchestras, The System. They never made it big, but pound for pound, you know, William Milan put an orchestra that was unbelievable. I got some of it. One of these days, we could listen to the records.

Garcia: [00:55:36] I mean they used to… First of all, they were all young, you know… Nuyorquino—before Nuyorican, we used to call ourselves Nuyorquino. Young, from the neighborhood, all from the neighborhood, and they all got together. We’re talking about like teenagers, you know. And they put this orchestra. It used to be called Loqueta Cimarron. No, no. What was the name of it? That was another good orchestra also from the neighborhood.

Lewis: Cimarron?

Garcia: [00:56:16] Yeah, Cimarron, yeah. Laqueta—oh no. Shit, I can’t remember—something erased my mind. Pero, anyway… When they used to play, man, they had a rhythm. I mean even Joe Cuba became almost the biggest Latin band in the world, and they were also from East Harlem.

Lewis: One sixteenth?

Garcia: Yes. You know…

Lewis: I think his wife—

Garcia: …that area.

Lewis: —still lives there.

Garcia: Oh, yeah?

Lewis: In the area.

Garcia: [00:56:52] Well, you know, they were from East Harlem. My cousin used to play with him. He used to be one of his timbaleros, and my cousin used to live on a Hundred and Eighth Street. Pero—

Lewis: What was his name? Sorry.

Garcia: Joe—oh, my cousin’s name?

Lewis: Uh-huh.

Garcia: [00:57:08] Joe—Jose Garcia. People used to call him Joe. He started with Joe Cuba, but then he left because they started using a lot of drugs and he felt, “I don’t want to go…” He became a very wealthy engineer, my cousin, you know? Pero, he used to be with Joe Cuba and all those guys.

[00:57:51] Anyway, going back to the story, where was I now?

Lewis: What the Lower East Side was like when you lived here.

Garcia: [00:57:40] Oh, okay. So, it was interesting and then there was different gangs. There were several different gangs of Blacks, Puerto Rican, Jewish, eastern European. In some cases, we might have a problem with each other and even the Puerto Rican’s gang had different atmospheres among them. Because there was—the Puerto Ricans that was here from before World War II, and they were more Americanized and then there was the Puerto Rican that just had come from the island that didn’t speak English, you know. So, there was differences, between them. Pero, in general, they would support each other if something comes up.

[00:58:39] And then the other thing is—what you call—a lot of people were poor, but they struggle, and then they tried to survive.

Lewis: It’s okay.

Garcia: [00:58:53] And they tried to survive, as people. And the Jewish community dominated the markets. That’s not necessarily bad because a lot of stuff that they sold was really financially cheap, not necessarily cheap in quality, but pricewise, you know. And Orchard Street was the biggest center for clothing… So, a lot of them… We always used to goof with the Jewish people because, boy, mostly all of them learned Spanish [smiles] at least enough to sell a blouse or to sell a pair of pants, you know? But it was interesting. And then the different foods, I mean Chinatown, the Jewish knishes, and all those things that we all experienced and then we had our own food and our own products.

Lewis: You had said earlier that… You had referenced to a time when you became politically aware, and so being a John Wayne fan became challenging. What were some of the things that were happening at the time that you—made you politically aware?

Garcia: [01:00:23] Well, the first time I experienced getting involved in politics and what I… It was two major things. One thing was the Kennedy campaign, President—

Lewis: John?

Garcia: —Kennedy, John [F.] Kennedy.

Lewis: JFK [John Fitzgerald Kennedy]?

Garcia: Yes. A lot of the Puerto Rican communities supported him. So therefore, in different stores and different locations there was being— preparation for campaigning, leaflets, getting that kind of active, distributing, talk to people. And then, what do you call it? We also helped with the Cuban—raising money for the Cuban Revolution. The Puerto Rican community used to throw parties, and the Latino community in general, too, used to throw parties and raise money to send to Cuba. And basically, that was the beginning of my interest in politics.

Lewis: Was it the general Puerto Rican community, or were there folks who were nationalists or independentistas or—

Garcia: [01:01:59] General, general, yeah. General, the Puerto Rican community. And then I also used to go meetings of independentista, socialista, _communista, _you know? People used to ask me, “Chino, what the fuck are you? [Laughs] A communist?” And I used to say, “Look, I just want to learn. I don’t believe… I don’t belong to any party or any particular group. I’m learning.” And it’s true! I was learning, you know?

Lewis: You had mentioned… When you were talking about gangs, you said, “we”. So, were you also part of a gang?

Garcia: [01:02:44] Oh, yeah! Since the… I was part of a gang, I think, since the mid-fifties—since I was around twelve years old, eleven years old.

Lewis: And what was that like?

Garcia: [01:02:59] It was, I mean, the original reason a lot of us joined the gang is to—if anybody messed with Puerto Ricans, we would go confront them as a group, and we did. Later, the gangs started getting involved in crime and drugs. And to be honest with you, I never joined the gang to be a criminal, [laughs] never. But then, for a while, you sort of got involved in some of those conflicts because you are part of a group. I really felt very strongly that I did not join to go beat up people and rob or anything like that.

[01:03:57] So, therefore… I went to Puerto Rico and lived there for a little bit more than a year. And the reason I went to Puerto Rico, because my father and mother felt that maybe I won’t—I would change my mentality. You know because my mother and father knew that I wasn’t a criminal. And basically, when I went to Puerto Rico, there, I was in a different atmosphere, always working and always spending with family, going to the beach, and things like that. So, I wasn’t hanging around with—I mean I would hang out with my cousins and that kind of stuff, but I wasn’t really—what you call it—involved in anything that was negative in Puerto Rico.

[01:05:06] So when I came back, you could feel that a lot of the guys in the group were really getting sick and tired of that, you know? At that time, the Johnson administration started, I think, in 1964 when he became president, you know, the Real Great Society. I mean the Great Society, and there were social workers and all kinds of people coming down, truant officers, and trying to offer us… A lot of us felt we could do the same thing you’re doing, so therefore, we could do it our self. We could put together programs. We could put together… I mean if we put together a hundred people to beat up on some other group, we could also put a hundred people to do other things.

[01:06:21]And that’s where it started catching up. You know what I mean? Doing workshops, organizing activities, and we rented an apartment right here on Sixth Street, on six of—well, first of all, we were using a youth center that used to help homeless kids. So, we asked the priest if we could use the subbasement to meet and to—and he was—he got along with us very well. That was Father Pat Maloney.

Lewis: And what was the church?

Garcia: [01:07:05] No, it wasn’t a church. It was a youth—Catholic center for youth, and they basically helped a lot of kids with a place to live. It was a—what do you call that—like a tenement building that they turned into a youth hostel, they called it, when you give them beds.

Lewis: Yes.

Garcia: But they concentrated on youth. When I was younger, he helped me out in court a few times. Basically, they would go to court and help the kids out of jails and look for jobs and things like that.

Lewis: What were you in court for at that time?

Garcia: [01:07:53] Oh, a few criminal… Mainly theft, and… One time I got—I went to court for attempted murder, me, and a few other people. Remember Loco? You ever met my friend Loco Feliciano? Yes, him. Me and him, we both got arrested. Pero anyway, in general though, it was an interesting place because there was a lot of young people upstairs, which some of them were our friends, pero he let us use the bottom floor for a few years. And then after that, we went and rented an apartment, you know?

Lewis: And you were a teenager then still—

Garcia: [01:08:44] Yeah. The apartment was like the headquarters for… And then one time, one time… PBS, when PBS was first starting, PBS did a youth forum, and they invited us to participate. So, we sent this guy named Turban to go and represent us, and he did a really good job. He came out of prison, and he joined us. I can’t remember his full name at the moment.

[01:09:32] And then, a few days later, this guy and his wife, they come to the apartment that we had over here on Sixth Street and said, “Hey, hi, I heard this guy named Turban the other day talking on that forum that PBS had. And I really want to see if I could be of some help.” So, I told him, “And what do you do? What’s your specialty?” And he told me, “Oh, I’m a high school teacher, and I deal with a lot of problem teenagers in Harlem.” He was a high school teacher in Harlem. I told him, “What’s your name?” He said, “My name is Jack Tannenbaum” And that’s how we became… That’s when he started, and he did a lot. I mean, one thing good about Jack, he was a great professional. He did his job. But whenever he had an extra hour for him to help somebody, he will do it no matter who they are, you know? He would always take that time to go help somebody. He used to work in rough areas in Harlem and the Lower East Side, South Bronx. So, basically, he dedicated his life to be helpful, and that’s how I met Jack Tannenbaum and then he became one of our main people—volunteers—throughout the years, you know?

Lewis: Now, I remember you being in books like Down These Mean Streets or there’s another book about gangs, Bandana Republic.

Garcia: [01:11:32] Yeah, there are some books. I don’t even remember...

Lewis: Yeah.

Garcia: [01:11:35] I think one time Taina said, “You know dad, the other day in my book club we were reading this book and they mentioned you.” [Smiles] Well, you know, yeah… I am in a lot of articles—national, international—not I, us. It depends on who they interview in the group that day. As a matter of fact, a new book just came out, you know? Let me show it. Oh—

Lewis: We’re attached to the microphone.

Garcia: Okay, Let’s stay attached another fifteen minutes or so.

Lewis: All right.

Garcia: All right?

Lewis: So, one of the things that… You had mentioned in terms of like the other political—the political context that was going on in terms of the Johnson administration and JFK and Cuba. It was also the time of the Civil Rights Movement. And I believe there was a time when you had told me that you—that CHARAS and the Black Panther Party, that folks were sharing, I think in the Christodora, some building down here?

Garcia: [01:12:39] Yeah. We—

Lewis: So, how did that happen?

Garcia: [01:12:43] The Christodora House used to be a settlement house. It was one of the first settlement houses. It’s part of all that the whole system of settlement houses. And then they moved somewhere, I think, to Harlem. I think they moved to Harlem because a lot of these centers, they were saying that the Lower East Side was losing the population that they was… They established themselves—to serve. I mean, we’re having that same problem now with the Boys Club on Tenth Street. They say, “There’s no more poor kids or no more kids in trouble.” Which we disagree. The thing is, it’s a different thing. You know, it’s a different way. You are here. We could still help a kid in Brooklyn, [New York] if they’re down-and-out, we could still help a kid in Chelsea, we could still—you know, because all those communities still have problem youth.

[01:13:54] So anyway, basically, the Christodora left the neighborhood, and they turned the building over to the Department of Social Services. You know the Welfare Center on Fourteenth Street? They gave it to that Division, and they used to be right here on Christopher Street—I mean in the Christodora on Ninth Street and Avenue B. So anyway, then they decided to move to Fourteenth Street, and they claimed the reason is because it’s more convenient for people from Manhattan to get there. Which is true. So, they decided to move there, so they emptied out the building, and they left.

[01:14:42] So, the building was empty, owned by the city, and it was empty for three or four years. And we told the city, “Look, that building is empty. Let’s put it back to use, some social program—homeless.” There were a whole bunch of bedrooms upstairs because that settlement house used to give rooms to people. I think men and women both. So, they had really nice little rooms, like hotels, up in the upper floor, a whole bunch of them.

[01:15:28] So, we took it over. And a lot of—and we asked a lot of—and when I say we, meaning, at that time, we used to call ourselves the Real Great Society—us and a few other groups, and we figured we’ll manage it. The thing is that that building was too big to manage. One of the biggest problem is that it has an elevator, and managing that elevator was almost impossible, you know? So, therefore, we couldn’t use a lot of the upper floors because we’re talking about almost thirteen, fourteen stories high.

[01:16:19] Pero, then where were some group of people that started squatting in the building, and they started harassing people, and people in the neighborhood. A lot of the neighborhood were getting pissed at the people in that building and then… I mean, it’s not like when we took over El Bohio, they immediately started giving services. And this time, since we had the experience of the Christodora building, we didn’t allow no bullshit. Because sometimes these people go into meetings, and they start talking this and—you know? People give some of those nuts leadership and then it becomes a nightmare. When we took over El Bohio, we didn’t let anybody throw us off. Immediately, we confronted people that we felt was all crap and no action. You know, you could see when people are real—when you give them tasks and they all start talking and they don’t do anything. We would confront them quickly, “Look, you—” you know, basically from the experience that we had with the Christodora House. So, that’s how come we were so successful with the El Bohio. That a lot of us didn’t want to hear the same crap we heard before.

Lewis: Did any of the groups that were in the Christodora House migrate over to El Bohio and stay involved?

Garcia: [01:18:04] Oh, two different periods. The Christodora House was more in the sixties, and El Bohio was more in the late seventies, early eighties, so two different, not necessary—you know… The main group was CHARAS. When we moved into El Bohio, the main group was CHARAS and Adopt-A-Building. And between the two of us, we had a good team of people, and people that do things. They’re not just bullshitting, or you know, talking about dreams and that kind of thing. Dream, pero let’s do it, okay? Let’s not just talk about. Let’s actually do it, you know.

[01:18:55] And you could notice whoever... Because El Bohio needed so much physical help that you could—that bullshitters won’t come around. [Laughs] The people that only talked crap and always talking all kinds of—they won’t come around because you had to work. If you want to talk, you better work too. You better paint, you better do plastering, you better clean the garbage, and that kind of stuff. So, it worked! It worked. We were more disciplined.

Lewis: When was, in terms of… And we’ll do other interviews, and there’s a whole lot of history that you have to share, but in terms of the housing movement at the time, what were the—you mentioned squatting, but what were some of the—and the bad conditions in the tenements. What were some of the struggles of the housing movement during this time?

Garcia: [01:19:52] Well, at that time, was fires. I mean, there were fires burning all over the place.

Lewis: In the seventies.

Garcia: Yeah, especially in this area of the neighborhood. But also, south of…

Lewis: Houston?

Garcia: Houston.

Lewis: So, when you say this area, between Houston and Fourteenth Street?

Garcia: [01:20:19] Yeah. A lot of fires in between Avenue A and… Avenue D. A lot of the fires took place there. At one point, I see—you could see Marlis’s photographs. It looked like Berlin, during World War II.

Lewis: And these were fires set by landlords?

Garcia: Yeah. Yeah.

Lewis: What were some of…

Garcia: For insurance purposes.

Lewis: What were some of the housing struggles that you were involved in in the seventies? You had mentioned homeless folks a couple of times.

Garcia: [01:21:00] Well… I started doing tenant organizing in the sixties, around sixty-five. Then, when all these fires started coming around, we had to figure out a way how to restore some of these buildings, somehow. I think it was 1971, CHARAS and Adopt-A-Building and a few other groups, we started talking about actually renovating one of those buildings with volunteers and future tenants. And that’s where the whole Sweat Equity movement started.

The first building that we chose to do was across the street from here. But again, that started the same thing that happened in the Christodora. A whole bunch of guys come and they’re all talking [imitating guys making noise] and nothing. So, we decided to do another building, and this time—which is 519 East Eleventh Street. This time—we didn’t allow that, like we did with El Bohio. We didn’t allow that to happen. I mean, you know, you have to actually produce, or leave. You cannot. And you worked. It was a serious group of people.

[01:22:45] The Sweat Equity Project was sponsored by Adopt-A-Building, and brothers and sisters from CHARAS got involved putting it together. And then they…We were lucky. We had a guy named Michael Freedberg. He came, and he was just like a young guy, and he decided to sort of work with us, and he became like the major leader in putting together packages and literature, with other people too, you know? Adopt-A-Building helped out putting together proposals and things like that to HUD, to HPD, and to other agency foundations. And little by little, the project got done! But I give a lot of credit to people like Michael Freedberg, Eddie Caraballo, even Luis Guzman and Luz [Marina Rodriguez] used to be some of the volunteers working in that building when they were young, you know? And it worked—more discipline... Then once in while Bimbo would come and Jorge Blandon, and they would sing some songs, and entertain the volunteers. You know, and basically, you know, it worked. I mean the people still—they’re still low income and there’s still people living there.

Lewis: Julio and Aida del Valle, is that their building?

Garcia: [01:24:35] Yeah, pero they left. They retired in Puerto Rico, so now, his son has the apartment.

Lewis: How did y’all pick the folks that would live in that building?

Garcia: [01:24:52] Well, neighborhood workshops were discussed and then little by little, people volunteered, and you could see… You know, in that building, you had to physically work hard. You just cannot come around and talk and smoke a joint and things like that. You could smoke a joint, pero you’ve got to work too. I mean basically, it was a… And the way we chose them is the more you participate, the more you have clout, you know, to get an apartment.

Lewis: So, you all took—kept track of the hours people worked?

Garcia: [01:25:35] Yeah, yeah. People had to write down. We said that each hour is worth ten dollars. So therefore, we had to keep—people had to sign in and sign out when they finished. Pero, technically, everybody had to do physical work. You just cannot sit around or stand and talk.

Lewis: Well, I know our time for this session is going to end soon, so I want to fast-forward a little bit to January of 2000, when the cofounders of Picture the Homeless—Lewis Haggins [Jr.] and Anthony Williams—first went to CHARAS. In Anthony’s interview, he says that… He tells us that Lewis had read about CHARAS in a newspaper article. But also, at some—at one point, Lewis had said he had gone to CHARAS to AA [Alcoholics Anonymous] meetings, so…

Garcia: [01:26:44] Yeah, he used to go the AA meetings.

Lewis: Tell us how you first met Lewis then, I guess?

Garcia: [01:26:51] Yeah, I met Lewis. You know AA would take breaks, and they would go outside to smoke or something, and I’d be sitting outside, and we’d start talking, and that kind of stuff. And then he mentioned a few times, “You know, I was reading some of your literature,” and that kind of stuff, you know? With AA it’s tricky because… AA members sort of don’t—they concentrate on their problem, and they don’t get too close to any center or location that they use. You know what I mean? But Lewis himself… There was so much literature in the hallways and tables that he started reading some of this stuff, you know? And he was telling me, you know that… Several things that he would like to participate, which is also to help him get out of that problem he had.

Lewis: What were some of the things? Do you remember?

Garcia: [01:28:05] In general, helping in housing, helping in, what do you call it, medical and food with homeless people. And basically… One day, he brought Anthony in. Because I don’t think Anthony wasn’t a member of AA at that time. I don’t know if he joined later, but at that time… I think he was just a friend of Lewis. I think they became friends around the tracks in Midtown. You know, the railroad system there, the—what they called the terminals, and a lot of those guys were buddies from there. And he brought Anthony, because he told Anthony about us, and Anthony wanted to actually see us, and we were all talking.

[01:29:19] I think it was Armando Perez, Ken, and Tony Arroyo. We were all talking when they walked in, and they sat down and talked to us. And they said that they wished that they could form an organization, they become homeless advocates. So, one of us asked them, “Exactly what do you mean by that?” I think Anthony was the one that explained more than Louie exactly. Lewis said a few words, but Anthony had a stronger opinion, I think. They was thinking of doing it on their own somehow, but they didn’t have resources and things like that. So, I told them, “Well, you know, resources are all around us. So, you see that empty desk? You guys use that with the telephone.” There was an extra phone that somehow we—we got a whole bunch of lines. I can’t remember where the fuck… I can’t remember where we got all those lines, all those telephone lines. Pero anyway, I told them. I told them, “You know you could start making phone calls and start meeting here with your friends, just like AA meets here and begin the process.” And that’s how they started. I mean, I was very… Because** **Lewis used to go to the AA meetings a lot, so he really was making an effort to get away from that problem that he had, alcohol—and that shows seriousness in a person.

[01:31:34] Anthony, I didn’t seem him much because he really wasn’t—at that time, he wasn’t a regular in the meeting. He just used to come by once in a while to say hello to Louie and a couple of other guys. Pero, he never was like in the meetings like Lewis was. And basically, that’s how he started. And then they knew… Anthony told me that he knew Al Sharpton, I think, at that time.

Lewis: Lewis knew Sharpton.