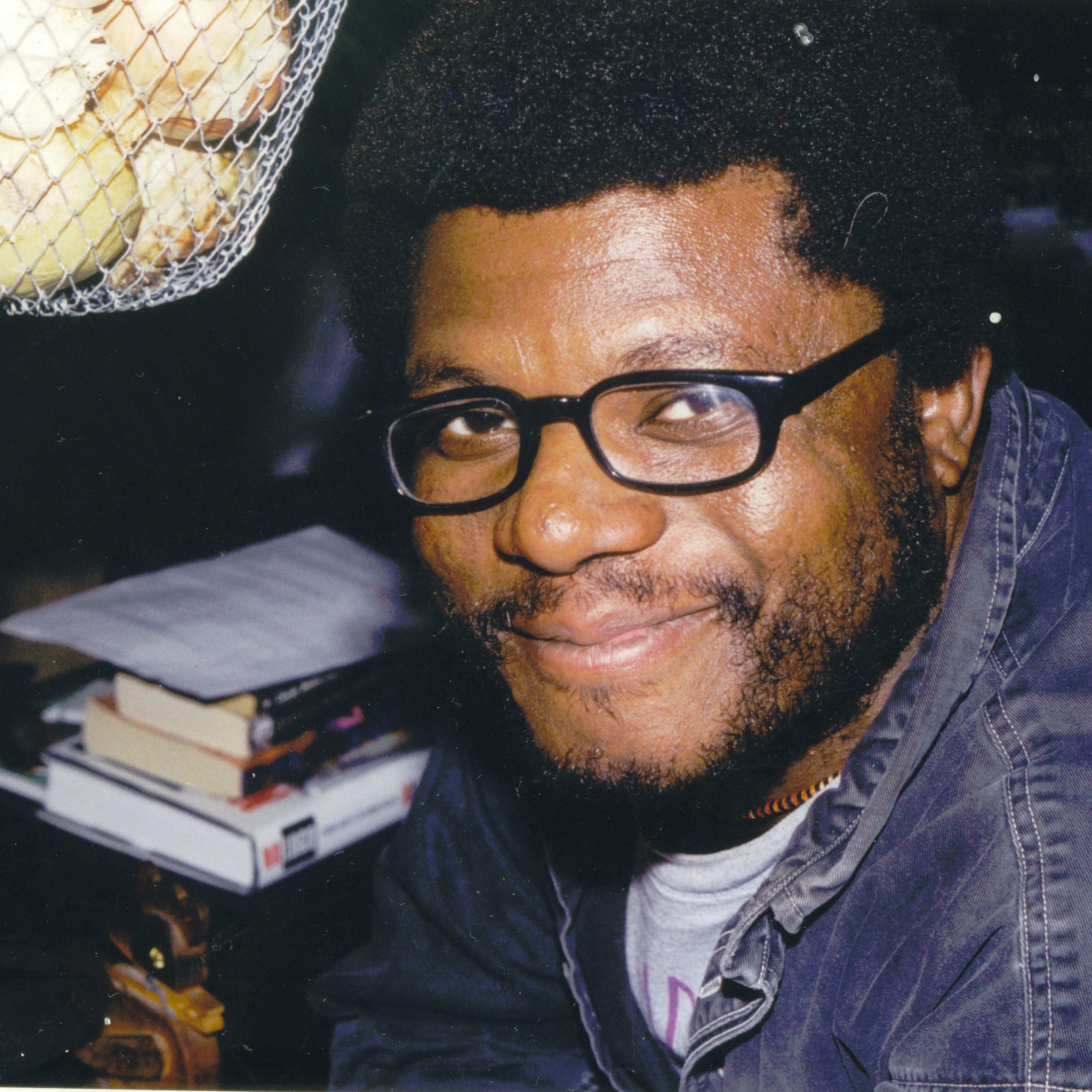

Anthony Williams (Interview 1)

This is the first in a series of three interviews with Anthony Williams, co-founder of Picture the Homeless (PTH), for the Picture the Homeless Oral History Project. The interview was conducted in a coffee shop in Baltimore, Maryland by Lynn Lewis on January 2, 2018, and primarily focuses on Anthony’s childhood and youth and current work in Baltimore to end homelessness.

Anthony Williams was born and raised in Baltimore, Maryland. He describes being born into the system, specifically being raised in the foster care system and group homes. He describes the pain of being removed from his elderly first foster mother, who was unable to care for him, although he didn’t realize it at the time. He was told at age nine, “In my second foster home, my foster mother, Miss Annie Mae Sanders, got really mad at me. I don’t know what—I did something. She got really mad at me. And she goes, “Your parents were bums, and they lived in abandoned properties. And you’re going to end up just like them.” (Williams, pp. 4) Well, I did.

He began drinking and smoking cigarettes while in elementary school, influenced by his older brother who was in foster care with him for a time. Heavily medicated as a child, he didn’t do well in school, and described sleeping a lot in class and the violence of his foster parents. The Baltimore city of his youth was a violent place. While in middle school many of his friends and acquaintances were killed by guns and other forms of violence, including his best friend. When someone was murdered the police drew chalk lines around the body and as a child and youth, he and his friends routinely came across chalk outlines of bodies and puddles of blood.

Anthony recalls his early teenage years in a series of groups homes and foster care, and began running away around age eleven. He was recruited by a Christian cult as a teen, and they moved him from Baltimore to a series of safe houses in Philadelphia, Virginia, and Pittsburg. He left the cult for good at age twenty but had a hard time staying in one place. Joining the church was his way to escape from the violence around him and find family. He later realized the leaders were enriching themselves off of the members.

Anthony returned to Baltimore in 2015 and became involved in organizing with other homeless folks and advocacy in the Continuum of Care. His interviews ends with critiques of the homeless service system as well as of Federal HUD’s investment in and oversight of the creation of housing affordable to the most vulnerable. He says, “If you’re getting money for homeless services and programs, provide those services and programs, right?! If it’s an issue with housing, and if HUD is giving the city money for rapid rehousing, then get rid of these stupid-ass definitions, and start housing people, and stop holding them hostage. Because that’s what all this is doing.” (Williams, pp. 23)

As Anthony reflects on his life today, he says, “You don’t really know how much power you have, until you really discover it, and you use it, and you see it working. And it’s not only working for you, but it’s also working for other people. So, my transition from homelessness in Baltimore as an adult, has also helped me to help thousands of other people. That’s why I’m happy, because I can make a difference.” (Williams, pp.24)

He reflects on how he was able to learn about the system through PTH, from Lewis [Haggins] and you [Lynn Lewis] and is working to hold the [Baltimore] city, and in particular elected officials, accountable for decades of devastation in Baltimore, including the loss of jobs and the prevalence of abandoned property. He challenges the people and organizations that use homeless statistics and homeless people, but push for housing that won’t reach the most vulnerable folks with the lowest incomes, and declares, “we’re not going to sit here and be pimped by you.” (Williams, pp. 27)

PTH Organizing Methodology

Being Welcoming

Representation

Education

Leadership

Resistance Relationships

Collective Resistance

Justice

External Context

Individual Resistance

Race

The System

Foster Care

Social Worker

Medication

Prison

Jail

Psychiatrist

Abandoned Property

Streets

Runaways

Women

Neighborhood

Group Home

Program

Cops

Police

Drinking

Home

Art

Religion

Bible

Work

Christian

Violence

Detox

Housing

HUD

Services

Chronically Homeless

Coordinated Access

Ineligible

Continuum of Care

Power

Bathrooms

Shelters

Privatize

Accountable

Jobs

Developer

Direct Action

Protests

Statistics

Affordable Housing

Area Median Income

Pimped

Vacant Buildings

Baltimore, Maryland

New York City

Organizational Development

Movement Building

[00:00:00] Greetings and introductions. Anthony Williams, born and raised in Baltimore City, placed in the foster care and never adopted. The foster mother who raised him until age eight had a big impact, a social worker removed him from that home.

[00:02:47] Placed with a new foster family with older brother Johnny, hadn't realized that I wasn’t taken care of properly, brother wasn’t happy with me being there. I was taking a lot of medication, falling asleep a lot in school.

[00:05:57] Baltimore City is a lot of pain and hurt, a child of the system, I feel like a successful human being. Second foster mother got mad at me and said “your parents were bums, they lived in abandoned properties.” I didn’t feel loved. Once she beat me in the back with her fists and I hit her back.

[00:10:39] Ran away, in the streets of Baltimore, at age eleven, the Fellowship of Lights took in runaways but reconnected him with foster parents, they asked him to come back, bought a pair of shoes, ran away again to Fellowship of Lights. staying longer. All my social workers were white and gorgeous, no Black social workers.

[00:14:09] Next group home was Baptist Home for Children, learned how to sneak off the property, used allowance to buy Playboy magazines, was uprooted again after six months.

[00:20:24] At age twelve, went to the Boys Home Society, a long term program, I was a big hash smoker, getting into a lot of fights in the group home, seeing a psychiatrist.

[00:24:50] As a child, only exposed to professional white women with good jobs, that was the help I got, was placed into an after-school job program but grades started slipping and was pulled from the program.

[00:27:30] Got drunk in the alley, near the group home, cops put a gun to my head, my first experience with Baltimore City Police Department, fifteen years old, handcuffed to a chair in Central Booking. Older brother was an alcoholic, they used their lunch money while still in foster care to buy alcohol and cigarettes.

[00:31:07] My older brother was my influence, didn’t have the greatest relationship, every time brother got locked up was for issues with women, including rape. While still at foster home brother was stabbed and taken to the hospital.

[00:37:36] The Boys Home Society was a good experience, there were different levels and payment for doing chores, got in trouble for sneaking girls in, being rebellious, stealing money, got caught and placed back on orientation, worked my way back up.

[00:43:18] My getaway was Walters Art Gallery, I went to an art show by a religious group. The people seemed so happy, my girlfriend's in machine shop and I’m in welding school, prayed with the people at the art show, gave them the number to the pay phone to call me.

[00:45:17] The group called me, invited to a Bible studies meeting, I liked that the people were mixed, and all lived and worked together. I get converted and stated to pull away from the group home. My girlfriend hung up on me when I told her.

[00:48:14] I got involved with going to meetings, signed out from the group home to go to New York, the Fellowship gave me a key to the house, I became a teenage fanatic, the group home tried to talk to me, I had stopped drinking and getting high, less fights.

[00:51:29] I ran away from the group home at seventeen, still a child of the state, all-points bulletin, the church sent me to different satellite houses until I turned eighteen, was working in their carpet business.

[00:54:40] Left Pittsburg, to go back to the Lamb House, the only education was through the Bible, I couldn’t go to school, church was too demanding. I had a problem being a follower, whatever the leader asks of you is what Jesus wants. The leader of the church bought mansions and yachts.

[ 00:57:35] I was looking for something, was mislead, young, and targeted. That’s what they do. I left the church and emotionally was messed up, brainwashed, and would go back and forth for years, in between until age twenty. That’s an important piece of my life. Other Picture the Homeless members had also been involved, they learned how to do outreach with them.

[01:01:04] Baltimore was violent during his youth, we always had access to guns, we would see chalk lines around the neighborhood when someone got murdered. The chalk lines stayed until it rained.

[01:02:19] Walking through the alley’s, seeing puddles of blood and a chalk line of a body, during elementary school. In middle school my best friend Frankie showed me his dad’s shotgun, I didn't want to hold it, a month later he invites a kid over, showed him the gun and the kid blew his face off. I didn’t go to the funeral, I sat on the curb, and wept. I was dating his sister.

[01:06:31] All my friends are dying around me, being killed. I was in middle school, my brother committing murder, they felt I couldn’t handle a full day of school, I was really out there, not understanding. My foster father had guns; I understood the seriousness of a gun.

[01:09:41] I had to get away and escape the stabbing and killing. The religion was that, they took your story and used it to benefit their agenda, provided you with resources, we all lived together. I was taught that you’re either right with God, or you’re not and if you’re not, you’re going to hell.

[01:13:15] I can’t go back, I will die and go to hell, came back to Baltimore at age twenty, left the church, I couldn’t stay put, went to New York where I had friends, every time I came back to Baltimore, the violence, guns. Now it’s a whole other level with our young people.

[01:15:25] On a train on my way to work, six young brothers on the train, they were scary, they intimidate people, I try and build bridges with them but if there's a group, don’t even bother. I got into an argument with a young kid, he wanted to show off in front of his girlfriend, I had to fall back.

[01:19:11] We got work, people don’t want to do it, they would do anything not to do the right things, to help people in Baltimore. The right thing would be to do your job, if you’re getting money for homeless services, start housing people.

[01:20:35] Coordinated Access is a problem, finding too many people ineligible, I went through the training, it was terrible. You don’t know how much power you have until you use it and see it working. My transition from homelessness in Baltimore as an adult has helped me help thousands of other people. That’s why I’m happy.

[01:25:21] I’m happy because I’m able to do what’s needed for myself and for other people. Doing the inside work for myself, which gave me the confidence to do the outside work.

[01:26:54] They wanted to privatize the Continuum of Care, I went against it because if you privatize it we can’t hold the city accountable. With fundraising what part of that money goes directly to homeless people. The pain is still here, I go to the house that I basically was born in, there is a baby that’s abandoned. I talk about that and make sure they hear it. This is my reality.

[01:29:18] I walk past buildings where people lived and had good jobs, in my neighborhood there were no abandoned properties, where did all those people go? The city council just sat here and watched that happen? This was created! You have the money, you’re lying to us.

[01:31:16] It makes me happy and it’s worthwhile to try and crack that nut. We’ve gotten people in positions of leadership through the Continuum of Care. HON [Housing Our Neighbors] is the guts and gears, does the direct action. They speak highly of Picture the Homeless. Everything they learned, they brought back here and put it in work, did the building count here and a report.

[01:33:18] They got the housing roundtable working on the twenty/twenty campaign, Housing Trust Funds, they’ve been using homeless statistics to push the twenty/twenty, but we’re talking about people at thirty percent area income and below, zero income, that's the people we’re talking about.

[01:34:26] We’re not talking about affordable housing, and if you’re using homelessness to talk about affordable housing, we have to be there to make sure that housing is created for the most vulnerable. We’re not going to sit here and be pimped by you.

[01:36:23] The majority of the time I spent homeless I was able to make changes and make a difference for a lot of people, with Lewis, with you, was able to learn and understand the system. There were decisions I made that weren’t good, I take responsibility for that, but I also take responsibility for what I learned too. Our leaders are key, they’re homeless but they have power, they can lead and make drastic changes.

[01:38:55] You don’t have to be a "professional", homeless people can make a difference, can show you how to end homelessness. The survey – what do you want, and when do you want it? That was one of the first ones.

[01:39:42] We’re telling the city what we want, it’s not going to be one homeless people it’s going to be all homeless persons. We’re all leaders.

[01:41:43] Every time we talk about the homeless the first thing they say is what about all these abandoned buildings, you’ve got more abandoned properties than homeless people. It makes sense because homeless people keep saying it. They powers that be want to use everything to not to do it.

Lewis: [00:00:01] All righty. It is January 2nd, and I’m Lynn Lewis, and I’m here in Baltimore, Maryland with—

Williams: Anthony Williams.

Lewis: Anthony Williams! Co-founder of Picture the Homeless and much, much more than that.

Williams: Yeah [smiles] yep.

Lewis: So Anthony, tell me—tell me, introduce yourself to

Williams: Okay.

Lewis: —who are you? Who are you?

Williams: Yeah. Who am I? So, my name is Anthony Williams. Born and raised here in Baltimore City. Actually, I was born in Baltimore City Hospital, out on Eastern Avenue, which is now called Bayview Johns Hopkins [laughs] Hospital. And so, at a very young age—I was basically born into this system, the foster care system. I was never adopted.

Williams: [00:01:09] I lived at 1508 Luzerne Avenue, East Baltimore, next to a cemetery. I guess a two-family house, or maybe a one-family house. A one-family house, but big. And I had a, like a foster brother with me. And then he ended up—his parents came and got him. Then I remained to the age of eight. She had the most impact in my life—as survival, and just learning how to make it—by making friends, and by… You know, she showed me at a very young age, like, I had a lot of freedom for a kid that’s five years old. Any average kid is probably with their parents somewhere, but not me. I was either at a friend’s or you know, walking around the street and seeing different friends and people like that. But I was never, you know—so I had a lot of freedom with her, and then... So when I turned eight years old, Miss Schneider, my social worker, came and got me, and put me in a car. And it was a very, very sad day for me, I... Because I was looking out the window, and my mom was waving at me. And I was just disappointed. I just—I didn’t know how to feel.

Williams: [00:02:47] But so, I—so, they took me to a foster home where my older brother was. I didn’t know—because I was a child, I didn’t know the condition that I was in, as a child. You know what I mean? Like, I didn’t realize that I wasn’t taken care of properly. I wasn’t properly washed. I wasn’t properly bathed. I realized that when I got there, that they told me to throw all my clothes away, you know, “Go upstairs and get in the bathtub, and wash yourself. Throw those old man clothes away...” Really hurtful feeling, you know. And my older brother, Johnny, he—he wasn’t happy with me being there. He wasn’t really happy at all.

Lewis: How old was he?

Williams: [00:03:39] He was fifteen, and you know—he was forced to walk me to school. Because we went to Cecil Elementary School that I showed you. So he would walk me there, and you know, it just—you know, he couldn’t stand it, so anyway…. But [pause] so, I went to school. Again, I was taking a lot of medication. I was taking Ritalin, Dexedrine for hyperactivity. I was diagnosed, Attention Deficit Disorder, hyperactivity, at a very young age, and I used to… I remember my first—so I went to—so, would I get taken back to Baltimore City Hospital by my foster mother. And they would—and I would go in a room. And they would give me this cup of juice, which was orange. But it wasn’t orange juice. It was just an orange juice. And I would drink it. And I would fall asleep.

Williams: [00:04:47] When I’d wake up, I would have wires attached to my head. And this would happen like three times a year. Like, they would give me some kind of—they called it EEG [electroencephalography]. Not EKG [electrocardiogram], EEG. It’s something else. I didn’t even figure that out. And I was considered partially retardation [pauses] and I guess slow, as they say. Not very smart in school. But then I was sleeping most of the time and falling asleep in class, and you know, and then they said, “Well, maybe we should do something about his medication, because he keeps falling asleep.” And I just—I wasn’t adjusting well at all. No, I wasn’t adjusting. I mean, so much going on, and—you know, life’s just going past me really fast.

Williams: [00:05:57] Like I think—so Baltimore City, for me, is a lot of pain. A lot of hurt. And I believe that because of all that, it’s what made me the person I am today. If I wouldn’t have went through, I think, all those things that I went through, then I may not be the person I am today. And I’m very proud of—today, who the person I really am. And I’m really happy about my success as a human being, let alone anything else. It’s like I am actually—feel like a successful human being, and being very productive in life and in work. And I really care about the work that I do. And this is—some people say, “Well, this is your calling!” I mean, that’s—but anyway. So, that’s who Anthony is. You know, a child of the system that went through a lot of ups and downs in life, back and forth from group homes, to foster homes, to running away, to institutions, to psych wards, to prison, to jail… And then homelessness was the ultimate—I wouldn’t say smack in the face, but I guess the ultimate… Like it was expected, right? You know.

Williams: [00:07:47] I mean, one time my psychiatrist told me, he said, “You know, most people don’t make it. Did you know that?” He was a psychiatrist from Brooklyn, New York. He said, “You know, you still got your wits about yourself.” I’m like, “What? I still have my wits about myself?” He goes, “Yeah! You know, ‘Wherever he laid his hat was his home.’ You remind me of a guy like that. You ever heard that song before?”

Lewis: Papa—

Williams: I said, “Yeah. ‘Papa Was a Rollin’ Stone.’” “Well, you’re kind of like that.” I said, “Yeah, I am a wanderer sort of.” I’m living in an abandoned property at that time, too. And, you know what? In my second foster home, my foster mother, Miss Annie Mae Sanders, got really mad at me. I don’t know what I—I did something. She got really mad at me. And she goes, “Your parents were bums, and they lived in abandoned properties. And you’re going to end up just like them.” [Long pause] Well, I did. [Laughs]

Lewis: [00:09:10] How old were you when she said that?

Williams: About nine. Mm-Hmmmm. Yep. Plus going to get my switch to get my whippings, you know—and I wasn’t—I wasn’t… I think I was I wasn’t… I was in a situation that wasn’t good. I just—I wasn’t loved. I didn’t feel loved. And you’re not my fucking mother, you know what I mean? You’re not my fucking mother. You’re not my fucking father. Don’t fucking hit me. And I hate you—right? And one time, she beat me in the back with her fists, and I turned around, and I hit her back. And that’s when my whole relationship with my foster father and my foster parents, it just never was the same after that. And it’s like I was kind of like, ridiculed. Like, “How could you do something like this? What’s wrong with you? How could you hit her back?” You know, her husband said that to me. Like, “How could you do—that was like the worst thing you could ever do! Why would you hit your mom, like?” She was kicking my ass, man. She was beating the shit out of me in the bedroom, and I turned around and hit her back!

Williams: [00:10:39] Yeah, I ran away again, hit the streets of Baltimore. I’m eleven. I was—found myself wandering downtown, you know—from the foster home. And I don’t know what the hell I was doing. But anyway, I ran into some person, and they said, “You looking for a place to stay?” I said, “Yeah, yeah. Yep.” He goes, “Well, the Fellowship of Lights [Youth and Community Services] is on Calvert Street. Why don’t you go over there? They take in runaways.” I said, “Okay.” I went to Fellowship of Lights, knocked on the door. They let me in. Went up and did a little intake thing, told them who I was, where I—you know, I was in a foster home and got tired of getting beatings, and I guess I wasn’t being ‘good enough’, or... And I just don’t have nowhere to go.” So they gave me soap, toothbrush, told me to go take a shower, get ready for dinner, and get ready for school tomorrow, “Because you can still go to school?” I said, “Yeah!” “But just come back here after school.”

Williams: [00:11:53] So I stayed there for like two weeks. And what they did then, Ross Apology was the director of the place then. He had this beautiful dog, retriever—and so, he was real cool. He had this curly afro—white guy. [Laughs] He was pretty cool, you know—and he goes, “Well, so, we’re going to have your parents, your foster parents, come in. And we’re going to have a meeting with them. Are you okay with that?” And I said, “Okay.” He goes, “You think you’re ready to talk with them and try to come to some kind of resolution?” I said, “Yeah! Something, I guess. Yeah.” So, I went in the room, and they were there, and we talked, and they said, “Would you like to come back home?” They said, “Would you like to go back home, Anthony?” And I said, “Yeah, I’ll give it another shot.” So then—so, got in the car, left—took me to a tennis shoe store. Bought me a brand new pair of Pony’s, which was cool, and...

Williams: [00:13:13] But it just didn’t—it didn’t… It went back to the same thing, again. And I ran away again, back to the Fellowship of Lights. I stayed there longer. They found another group home for me to go to. They sent me another social worker. She was gorgeous, man. See, me and these white women, you know what I mean? I just—you know what? That was embedded in me. You know, “Anthony and his white women.” Like, it, you know—all my social workers were white and gorgeous and pretty. So how could I not be attracted? I didn’t have any Black social workers. I had all white social workers. So, how could I not be attracted to white women? It just was hard! But this one was pretty, blonde, young. I was, like, twelve and she was, like, twenty, you know? She had a little Volkswagen.

Williams: [00:14:09] And she took me to my next destination, which was the—aw man! What was—the Baptist Home for Children? It was called the Baptist Home for Children, on Greentree Road in Bethesda [Maryland]. This was a double building. They looked alike. They were twins. And it had these cottages. And they had the long-term boys, for like two years. And then I was like, six months. Our building was coed, so they had girls on one floor, boys on the bottom floor, food was excellent, a lot of recreation. They would take us summer inner tubing, you know, rock climbing. Then every Monday they would take us to the mall, and give us like ten bucks, and we could just have a free-for-all running through the mall. And then they’d bring us back. So… It was cool...

Williams: [00:15:18] I had this roommate, right? He used to always put candles around his bed. Like literally, he would put candles, light candles around his bed. [Laughs] And he was strange. He was a white dude, but he was strange, right? I never really talked to him, because I didn’t really earn a single room yet. Because they had them, but you had to be there a while. And then you could earn that, you know what I mean?

INTERRUPTION: Mic bumps, Oh sorry. It’s okay…”

Williams: So yeah. This guy was strange, man. Oh, he used to pile English Leather [Cologne] on him. He used to just pour this English Leather, all over his body. You ever heard of that?

Lewis: Yes.

Williams: English Leather? Aw man, he just—I don’t know if he even took a shower. He’d just would like, get up in the morning and like, bah-bah-bah, right? And you could smell this stuff, man. It’s strong, you know? I’m like man…

Lewis: I think it was popular then in the ’70s.

Williams: [00:16:14] [Laughs] Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. So anyway, him and his candles. So anyway, there was a girl there named Sunshine. There was a—I think there was a Spanish girl there too, named Marisol. See, I remember everything. Then there was this other light skinned girl that like… When they like, one evening we were in the basement, at the pool table. She gave me a—she showed me her breasts, and I fell in love with her. But then she had a boyfriend. [Laughs]

Lewis: What was her name?

Williams: I don’t remember her name. She was pretty. She was a redbone, light skinned—you know, “high yellow”, pretty though—gorgeous, so... But anyway, I ended up getting in a fight with this white dude. I think he was racist. But anyway, we got into a fight over something. And so, the resolution to the fight was… The counselor would be here, they didn’t give us gloves. No—he gave us gloves and he said, “You get to punch him once, and he gets to punch you once.” [Laughs]

Lewis: Oh, boxing gloves?

Williams: Yeah. But just once. So I punched him—boom. And he nailed—I mean, he laid into me, man. I felt it. [Laughs] I was like, “Is that it?” “Well, how did that feel?” I felt like, [laughs] I felt very, like, you know—I must be—this is the wimpiest fucking thing I could think of, you know? [Laughter] I hit the guy with not even force. The guy lays into me with all the force he had—anger and everything. But how come I couldn’t get that kind of energy up, you know what I mean? But anyway. So we got past that. And we would have these groups, you know. We had weekly groups, where we talk about our situation, how we’re feeling, what may happen in the future, you know, and...

Williams: [00:18:42] Oh, man! [Makes sound like “Phew!”] The director was from Newark [New Jersey]. Eva Vince. Blonde, beautiful, wow! Director, right? So this is what I would do. I would sneak off the property. Because I learned how to sneak off the property and go to the seven-eleven. So, I would sneak off the property, and I would take my allowance, and I would buy Playboy magazines, right? And I could buy them, right?! And so I had them in my room, you know. I kept buying them. I had a few of them. So, she found them, but didn’t tell me—but she didn’t tell me she took them, but she found them, though. But I didn’t—I wouldn’t go ask her.

Lewis: What did you think at the time happened to them?

Williams: Somebody took them. I guess [laughs] somebody came and took them. But—so, my last day there, she called me in her office. Beautiful woman, Eva Vince, yeah. She was the director of Baptist Home for Children. So she goes—so she hands me a yellow manila folder. And guess what was in it?

Lewis: Your Playboys?

Williams: No, it was a monthly—it was the year issue. It’s a thick issue. [Laughs]

Lewis: Oh, wow.

Williams: She had gave me that when I was leaving to go back to Baltimore. And I wanted to stay there. I really—you know, I finally had gotten used to a place, gotten used to people. Got used to, you know—but then again, I’m uprooted again! Here we go again. Uprooted somewhere else.

Lewis: [00:20:24] How old were you?

Williams: Twelve. I had just hit twelve, and I probably stayed there for like six months. So she says, “We’re taking you to the Boys Home Society. It’s run by a point system. We think you’ll do well there. It’s a long term Boys Home. You can stay there until you’re like twenty-six, or twenty… Something like that, as long as you stay in school and do what you’re supposed to do.” So, when I got there—I don’t know if you read that email. You know what? I—so my roommate, his name was Mico, African American from the East Side. He hung around with these really tough cats that I knew about. There’s one guy named Mutt. He used to hang out with Mutt and this guy named GI, they used to call him. They was really thugs in the neighborhood, you know. They were very well-known, wearing orange bombers and really mug—like, bulldog-looking, tough-looking cats, right? And Mico [laughs], I had to share a room with him. And so he had funky feet. [Laughs] So I had—you know, when I moved into the Boys Home Society. I came back to Baltimore. Remember I showed you the building where my room was?

Lewis: Yeah.

Williams: Well, I started out in not that room. I started out in a two-man room, a shared room with another guy. And so Mico has stinky feet, you know. But we got to know each other. He was like—I don’t know. He would always get in a fight with another friend I made named Darren Wilson. They would always get in fights in the hallway. Then it was this other guy, I forget his name—but real muscular. He used to lift weights, you know like—and he’d walk around, [imitates him] you know. [Laughs] Yeah. So, it was a whole crew of us. Then it was Pilgrim, Joe Price—white dude that talked Black and acted Black. [Laughs] For real, he was like—they called him Pilgrim. They nicknamed him Pilgrim. And, you know, he would bop. [Laughs] He would bop. And you know, we—we were friends, though. He had a kickass sound system. And so I would get him to make me tapes. And man, he had a real cool room. He had his own room. And then I ended up moving next door to him. He lived in the other room. He had a killer sound system. Aw man, turntables, he had speakers... And I was like, yeah.

Williams: [00:23:19] So, I was a big hash smoker. I was into hash. I really liked smoking hash. I didn’t like weed, marijuana. I mean, I did it. But I didn’t—my thing was hash. I would buy—I had a—there was a guy that—down the street from there, from the group home I showed you, that lived a couple apartments down. He used to sell me blocks for five dollars.

Lewis: Damn.

Williams: A five dollar block of hash. And I’d go there, every time I got my allowance, I’d go over there and get a block. [Laughs] And I had a pipe and I’d go in my room, and turn the music on, and, like [whistles]. It was just like, wow. Yeah, that was my thing, then. But I started getting irritated, irritable. I was getting into—I started getting into a lot of fights in the group home with other people. And I think it was—I think I needed a medication adjustment. And so my social worker there—wow. Diane Kay Powell—another redhead, white woman, gorgeous! That was my—that’s the in-house social worker, right? Gorgeous. And she would always drive me to my psychiatrist, which was another woman, that was a brunette, white and beautiful. And we would play ping pong and play pool together.

Williams: [00:24:50] See, this is—this is, this is my life as a child, being exposed only to basically professional white women that have really good jobs, growing up. And that’s what I was always around! Like, any kind of help that I got—that was the help that I got! And that was—well, I guess that’s what… If you’re exposed to something consistently and being always exposed that way consistently, nine times out of ten you’re going to be—you’re going to fall that direction. Me—like I fell in that direction. Like, I didn’t plan it. But I ended up finding white women more attractive than Black women! But because I spent a lot of time around professional white women, and that was my way of—that was the kind of help that I got! If I got help from Black social workers, I probably would have felt… Right? More—I’m not sure. But anyway, that’s how it turned out.

Williams: [00:26:01] So, Diane Kay Powell gave me a medication adjustment. But she was tough, though. Man! So, she got me into this after-school job program. As long as I keep my grades up, I worked for Brody’s Trucking, where I would go, and I would check the oil, clean up the garage for three hours after school and get paid for it. It was a program, after-school program—good program! So… But I, something went wrong with me, I think. So, my grades started slipping. I don’t know why. It could have been a medication. It could have been a lot of things. But anyway, my grades start slipping. So, one day I go into Diane Kay Powell’s office, and she goes, “Tomorrow, you don’t go to work. I’m pulling the program from you.

Lewis: Oh, wow.

Williams: I was like, “Why?” She goes, “Your grades ain’t—you’re not keeping up with your grades.” I said, “Yeah, but I really like that job! That was very important! I like that job. I really wanted that job!” “Nope, you can’t go. That’s it.”

Williams: [00:27:30] So, I got a couple friends together. I said, “Come on, man. I’m going to go, get a bottle—a fifth of Thunderbird.” Went out, got a fifth of Thunderbird, we drunk it in the alley, right? Not too far from the group home, you know—in one of those alleyways. Then I got really black—I went into a blackout, ended up running from the cops. The cops end up catching me. I rolled under a car, then the cops called me out, put the gun up to my head. Then threw me up against the car, roughed me up, busted mouth, grabbed me by my nuts, kept slamming me up against the car. That was my first experience with Baltimore City Police Department, fifteen years old. That was my experience. [Pause] They wouldn’t let me go to the bathroom. So I was handcuffed to the chair.

Lewis: In the precinct?

Williams: Yep, Central booking, downtown. So, I urinate on myself. And I was still intoxicated. So, one of the counselors named Underwood—who had a red Eldorado with white interior, Cadillac. Nice. So, I get in the backseat, I throw up all over his car. Yeah, I mean—so anyway, the guys at group home come and get me out of the car, throw me in the shower. I kind of vaguely remember hot water or cold water, being hit. And then they just—and then, so I find myself—I’m on my bed, butt naked, right? You know, “Wow, what happened?” He goes, “We put you in the shower, you know what I mean? We looked out for you Ant. You’re all right. You’re good.” [Laughs] I’m like, “What?!” So, I was like, wow. Bad experience. That was my first drunken—that was my first real experience being in a blackout, you know—fifteen.

Lewis: [00:29:55] You had mentioned before—one time before you showed me, near your elementary school where you would drink sometimes before school.

Williams: Yeah.

Lewis: What was that about?

Williams: Oh, I think my older brother was an alcoholic, big time. Big time drunk. No doubt about it. And so instead of going to the movies or going to do what we were supposed to do when we got money, when we had lunch money, we’d look around and buy Richards, buy a thing of Richards Wild Irish Rose. I was—I’m not the blame type, the type of guy that would say, “It was his fault.” But he introduced me to smoking cigarettes and he also introduced me to drinking. Because he used to blow these rings, off of the Kool cigarettes, blow these rings. I said, “Can you show me how to do that?” And he said, “Yeah! I’ll show you how to do that.” I never got it. I did it probably once or twice, but I never really got it.

Williams: [00:31:07] But he was the influence. He was my older brother. He was my influence. So, of course I’m going to be like… Although we didn’t have the greatest relationship. But later we started bonding a little bit. He built me a wagon, and we would ride the wagon. RK wheels and yeah. He was a funny guy, too. He could draw really well, very funny. Yeah, I got—yeah, so… But he had a lot of problems, a lot of sexual problems. He got in trouble a bunch of times for rape. He had a lot of problems with women, getting in trouble with, you know, like—he always got in trouble. Every time he got locked up was because of some kind of issue with women, and it was more so rape. So when he got—so when I—I hooked back up with him in the ’80s. And I asked him, I said, “Is it true?” He goes, “Yeah! It’s true, Anthony.” I said, “Wow!” I could imagine how many he didn’t get caught. But he told me, you know. It was my brother. We’re in a bar, drinking, you know? Yeah, so he says—he goes, “Yeah, it’s true.” That’s my older brother. But he had a rough life, no doubt about it. One day he came banging on the door in the evening, two stab wounds in the back, buck-fifty in his face.

Lewis: Where were you guys living then?

Williams: In a foster home. The second foster home. And they ended up—the neighbor next door ended up putting him in the backseat of the car and rushing him to the hospital. Punctured lung—they really tried to kill him. And he had this—he has a lifetime—me and him look alike. The only difference is he has a—from here to there, cut in his face. Usually that’s the sign of somebody that’s a snitch. But it could have been the stuff that he was doing too, that probably contributed to him getting that buck-fifty. But that’s what he got. And you know—yep. But so, yeah, that’s Johnny, you know. My foster mother would always say, “I worry about you. Because you look just like him. And I’m afraid that somebody is going to come after you, thinking that you’re him.” Because that’s how close we favor each other. And it’s true. We do look alike. I don’t know about now. But I know we—when I look at him and I look at—we’re almost, like, identical.

Lewis: [00:34:16] When’s the last time you saw him?

Williams: In the ’80s. And I think my cousin—my foster cousin has seen him. He said he thought he was homeless. Ricky—I went and saw Ricky. He’s—man, Ricky—he’s not doing good. You know, he had a really good job. He had to leave because of dialysis. Yeah, he—what were we saying? I lost my thought.

Lewis: You were talking about your foster cousin, and that he wasn’t doing well.

Williams: Oh, yeah, yeah—dialysis. He’s got to do dialysis and he’s looking for a liver. Is it a liver or a kidney?

Lewis: Well, dialysis is for kidney. But you can also have a liver problem at the same time.

Williams: Yeah well, he needs to get that.

Lewis: That’s rough.

Williams: He needs to get a liver and he’s... So, the last time I talked to him—I sat on the porch and talked to him, right before winter hit, you know...

Williams: [00:35:20] It’s like he knew that we were trouble kids—family.

Lewis: Troubled or trouble?

Williams: Trouble family. [Laughs] Like, because we would do stupid stuff like show up drunk all the time. And I did it once to him. And so he never really… So one time I went there when I was drunk. When I first got back here, I went to his house when I was drunk. And he—he said, “Why don’t you come back at a decent hour Anthony?” [Laughs] I said, “Oh, yeah. I’m sorry, man. You’re right, you’re right.” So, then I walked back downtown. But I went and saw him after that, and we talked and he sat on the porch, of course. He wouldn’t let me in the house. But that’s okay. He never did let me in the house. You know, he has a family, so... Not that I would do anything to the family, but you know—he, Ricky—he understood. I understood Ricky. You know, as kids we played together. We were great. We’d wear the same—almost the same things during Easter... But Ricky and Robbie, his brother died from AIDS.

Lewis: [0036:30] So their parents were your foster parents?

Williams: No, those were my neighbor’s grandchildren…

Lewis: Okay.

Williams: Mother died from diabetes, and the grandma took care of Ricky and Robbie.

Lewis: Oh, okay.

Williams: They’re brothers.

Lewis: So they were the neighbor’s grandchildren. Okay.

Williams: And we were friends. Ricky and Robbie was like the popular—we lived in the projects. They’d come. “Oh, Ricky and Robbie, yeah!!” Their mother was really nice. I remember her. First she lost—oh man, I don’t even want to talk about this… Diabetes is rough. I’m surprised I got it. But anyways—so yes. They kept—she ended up losing both her legs, and—you know, serious. She passed away.

Williams: [00:37:36] Yeah, so I—so, I think—so, where I’m at, at that point, after the Baptist Home for Children, going to Boys Home Society, that was a good experience for me. [Smiles] I went through orientation. I caught on real quick. I started out on level D, which you get a five o’clock curfew, two-hour study hour and three dollar allowance, every week. That’s how you start, on level D. Then I moved to level C, which—I got six dollars a week, for allowance, thirty dollar clothing request. And any chores that I did, I got a dollar for each chore that I did. And then, if I worked the kitchen for the week, right? That was like three dollars a day, added to the money, yeah. So, the point system—you got points for everything you did. If you got up and made your bed, emptied the trash, swept your floor—they would come around and check, and then they would give them points. And then once they add up at the end of the week, right? If you were over fifty-six hundred, or sixty-three, then that’s how high a level you’d go. So I made it to level C. I made it to level B. And I made it to level A.

Williams: Level A is ten dollars allowance, thirty dollars cash clothing allowance. [Laughs] Not a stipend, but you didn’t have to go to a—what was it called? I forget the name of the store. But anyway, we—oh, Trading Post, downtown. We used to go to Trading Post. So, but they’d give you cash, which meant you could go anywhere and shop. It was a luxury, right? Instead of having to go to the clothing—to you know, to get the same thing—khakis, shirt. But anyway, so that was an experience! I mean, I think it was a very good program. It was a very good program. I made—but I did wrong things when I was there—sneaking girls in and being rebellious. You know, not maintaining my levels, to the point where I got put back on orientation.

Lewis: [00:40:11] What did you do to get put back on orientation? [Smiles]

Williams: Well, it was this—so it was a… So, down the hall from us was this guy named Anthony Ashcroft, who like, was “Mr. All That.” [Laughter] Anyway—so, you know, he walks around... And you know, he gets—he’s going to into—he got into the Marines. So, he’s getting ready to go—so he has two piranhas in two different tanks. And he’d feed them goldfish. But you can’t stare at the tank. You have to act like you’re not looking, and then the piranha just takes one half of the body. [Choo!] Then takes the other half. [Choo!]

Lewis: Wow.

Williams: He had two piranhas, yep. Yeah, he had two piranhas in two different tanks. But we figured out that we knew how to open up each other’s doors, with the keys. [Laughs] So we go, me and Darren go and rip off Anthony Ashcroft for some money, and we go to the Oriole game. [Laughs] No, we go—oh yes, right, we go to the baseball game. We go to an Orioles game. [Laughs] We steal his money, go to an Orioles game, and come back. But we get caught. I mean, like, we got caught. And so being that we got caught, they said, “Okay, yeah I manipulated the key.” [Laughs] Yeah, so... Yeah, I got put on orientation, and then got off orientation. Worked my way back up.

Williams: [00:41:57] Then it was… So one day, we—me and Darren—we’re going to go to the movies. We got our allowance. We used to always, you know—we went to see Blue Oyster Cult at the Baltimore Civic Center. And we used to go see wrestling for six dollars a ticket. We used to save our allowance and go see the wrestling matches. Bob Backlund and all them guys, yeah. So anyway… So, what was I going to say? Blue Oyster Cult—oh, so anyway, we went to the Belvedere Theater, which is no longer a theater, but it’s still there. It’s just—I guess not abandoned. But anyway, 33rd and Greenmount was the Belvedere Theater—I mean, the Boulevard, sorry, the [pronounces with a long “a”] Boulevaard. It’s called the Boulevaard. Boulevaard. Boulevaard. It’s called the Boulevaard. The Boulevard—Boulevaard.

Lewis: The Boulevaard.

Williams: The Boulevaard.

Lewis: Okay, got it.

Williams: So anyway, 33rd and Greenmount—Boulevard. So, we go to see two movies, a double feature. Phantasm is one. And the second one was The Fog.

Lewis: I remember that.

Williams: So we go in and see those two movies. I didn’t get The Fog. But I got Phantasm. I really liked Phantasm. I didn’t like The Fog. It just—

Lewis: It’s creepy.

Williams: Huh?

Lewis: Creepy.

Williams: [00:43:18] Yeah. [Laughs] So anyway, we enjoy it. Did we smoke a joint before? We probably did. But anyway, we came out, and across the street is all these pictures of art. And I’m really into art. Because I used to hang out in the Walters Art Gallery, I used to always watch the Hitchcock films, the Hitchcock films, go see them in a theater. You know, that was my thing, the museum. That was my getaway.

Williams: But anyway... [Sighs] So, I see all this artwork. So, of course I’m drawn to it, because I love art. And the lady says, “Picture one starts here, John, Chapter Three.” It’s a religious group. So I went through the whole art show, and they explained each picture of John, Chapter Three. These religious people—but seemed so happy, so united, so together, you know? They go, “Would you like to pray with us?” Mind you, I’ve got a girlfriend too, named Regina Richardson. She’s—I’m in welding school, and she’s in machine shop at Maryvale. So we both [smiles] go to Maryvale after our regular school. Samuel Gompers [School] is a—[unclear] but that’s where, you know—so anyway, I had did—so anyway, we go to the art show and go to the art show. I pray with them, they give me these two booklets and, “Do you mind if we call you?” I said, “No, sure, you can call me. Here’s my phone.” We had a payphone inside, so we could just…

Williams: [00:45:17] And they called me! They said, “Hey, we’re having a meeting. Would you like to come?” “Where is it?” “Park Heights, 4511 Park Heights, the number five. We’ll take you there.” [Laughs] So I said, “Yeah! I’ll come by.” And these were Bible studies. So I would go there, and we’d all sit there, read the Bible, pray. And then—so, I started getting kind of like into it. I started getting really like—this is pretty—I kind of like this, religious thing.

Lewis: [00:46:00] What did—describe what you liked about it.

Williams: I was with people that were mixed, and they all lived in one household. Men and women—mixed, and had the same thing. They all had the same thing, which was the religion. They had the same thing. But they also lived together in a communal way, right—which was cool to me, right? And the brothers were working a carpet cleaning business, cleaning carpets. So that was cool, because they—and the sisters would do the phones! You know, answer the phones, and set up the jobs, and then the brothers would go out and clean the carpets. That’s how they ran the business. Later I found out that they was making two-hundred thousand a week nationally, that church.

Williams: But anyway... So, I get converted. So I’m starting not to—I’m starting to pull away from the group home, and people start noticing it. They know I’m doing better. But they see me pulling away from the group home. “That’s not good. He may end up leaving with these people. So, we’d better try to catch him before [laughs] he gets pulled in.” So, my girlfriend calls and I’m all zealous now with Jesus. I love Jesus. Jesus, Jesus, Jesus, Jesus. So then—so then, so she calls. I say, “Hey! How you doing? Hey, I believe in Jesus now.” And she goes, “Did you meet those people on the corner?” I said, “Yep!” Click! [Laughs]

Lewis: What?

Williams: That was it!

Lewis: Dang.

Williams: And she loved me, man. She would—I mean, she was great. She loved me to death, Regina. But I told her—when I started that religious stuff, man, she—click! That was it.

Williams: [00:48:14] So, I got involved with going to these meetings. So, they had a trip going to New York and I think I had enough points where I could sign out for the weekend. So the Fellowship gave me a key to the house, to come and stay overnight and then go to New York the next day. And I did. And I came back to the group home, without really no one saying anything. And I kept the key to the house. Because, “Well, you know, when you want to come, you can come. You know, work with the brothers and sisters, read the bible, you know—go out flyering, giving out flyers—carpet cleaning flyers.

Lewis: Doing outreach. [Smiles]

Williams: Yeah, doing outreach. [Laughs] So, I really got into that. I got to the point where I got zealous, became a fanatic, teenage fanatic, Christian fanatic. Jesus, I would do anything for Jesus. I would die for him. You can’t tell me nothing, because I know it all. I know the Bible, and the Bible is the way, and you Muslims better get your shit together because—I didn’t say that, but, you know—but you better get your act together, because Jesus is coming, and there is no Black Jesus. There is a white Jesus, and that’s the one you should be worshipping. [Laughs]

Lewis: The [unclear].

Williams: [00:49:49] You see Jesus on the track with the shepherd—with the sheep?

Lewis: Mm-Hmmmm.

Williams: That’s Jesus. I don’t know what Jesus you’re talking about, but the white Jesus is the Jesus that I’m talking about. [Laughs]. Anyway, so... You’ll find a lot of humor in this stuff. [Smiles] But anyway, so I start to go on this tangent, and then the group home tried to wheel me in. They brought me into a meeting, with my peers. “We want to talk to you, Anthony.” One of my friends there named—his name is Knox, Lawrence Knox. He saw the transition. I even led him to Jesus and read the Bible with him. You know I, converted—well, I led him to Jesus. But he didn’t—you know what I mean. Like, I led him to Jesus, but he didn’t…

Lewis: But didn’t stick?

Williams: Yeah, he didn’t stick. [Smiles] But anyway, so—but he knew that I changed. He was the one that could say in the meeting, “I don’t know why you’re giving Anthony a hard time! This guy used to break in people’s rooms and steal money. Now he’s talking about Jesus! What—he’s not doing anything wrong!”

Lewis: What’s the problem?

Williams: What’s the problem? [Laughs]

Lewis: And you were—were you drinking and getting high still?

Williams: Mm-Mmm. No.

Lewis: So, you had—you had changed in a lot of ways.

Williams: Yeah! And they saw it, less fights, I was involved with the church... I had the whole art show. I would show down on Howard Street at the Lexington—near Lexington Market. I was drawing them up on the wall. You know, I was really into it. I really enjoyed it.

Williams: [00:51:29] And I think before they caught on, I had left. I had ran away. With the—

Lewis: From the group home?

Williams: Yes.

Lewis: Oh.

Williams: I was seventeen. And I still was a child of the state, which meant that all-points bulletin looking for Anthony Williams, yep. So, I went—I went from 4511 Park Avenue to 6713 Woodland Avenue in Philly. Stayed there—no… Yeah, stayed there. Then Jim Griner, who was the leader then, at the Lamb House said, “Anthony, we got people coming here. We’re going to send you to one of the satellite houses.” So, they sent me to one of the satellite houses, because they knew where I was at. So, he sent me to another house. And then, they ended up sending me to Virginia to one of their houses and then, me being young and stupid or whatever, I got this feeling for my social worker.

Williams: [00:52:51] So, what do I do? I call her.

Lewis: Mm-Hmmmm.

Williams: When I’m at home by myself, I call, and I want to talk to her. But when you’re a Christian, you’re honest when they come back, you know. “What’d you do all day?” I said, “Well, I called my social worker.” “How long were you on the phone with her? Were you over ten minutes on the phone with her?” I said, “Yeah!” They go, “We got to get you out of here.” Ahhhh. So, the next day, they drove me to Greyhound and sent me to Pittsburgh. I went all the way to Pittsburgh, to a Fellowship house in Pittsburgh. And I stayed there until I turned eighteen. So, I stayed in Pittsburgh until I turned eighteen. And I stayed there, and worked with them in the carpet cleaning business. I liked the house. Lawrence Braylock who was into engineering, and you know, now he’s probably working for the government with some kind of secret technology. You know what I’m saying? That’s what he was into, like putting together devices. [Laughs] He was good at it. Yeah, so now I know he’s up there in the ranks, Lawrence Braylock. He married Miriam, so... But anyway, so I had a good time there. I really enjoyed being in Pittsburgh. I was kind of sad to leave—learned a lot there, traveled around there, ran into John Stallworth for the Steelers—you know, in the Northeast Mall. I remember seeing him with his Super Bowl rings. [Laughs]

Lewis: [00:54:40] Why did you leave Pittsburgh?

Williams: Oh, because it was time for me to go back to the Lamb House. That was my training center.

Lewis: Okay. Were you getting any education, like reading, and math, and all that stuff?

Williams: Only through the Bible.

Lewis: Okay.

Williams: I attempted to go to a vocational school nearby. But didn’t—it was just—the church was just too demanding, and I didn’t have the time. So, I didn’t really get my GED or nothing. I just continued working with the church. And which [long pause] it was a very unfortunate thing that happened to me. You know, I get born again, become a Christian. Stop doing all this stuff.

Williams: I had a problem being a follower and following people that you respect that is guiding you and advising you the right thing. So I took what was given to me, as the right thing. Because I was still young, I was eighteen. But I’m eighteen, so I do have some knowledge of _some things. _But when you’re a person pleaser, and when you are respected, or looked upon as a great person because of—being part of the leader, of being a leader in the church, as with being zealous and all those things, then whatever they ask you—whatever the leader asks of you, then you do. Because it doesn’t matter, because Jesus wants you to do it. Not the person—you mind, Jesus wants you to do this. It’s not that Stewart wants you to do it. It’s not that Jim wants you to do it, it's what Jesus wants me to do. Well isn’t that twisted? But that’s what it turned into. Like being brainwashed and believing in people that really were misguided themselves, and had no other—and what their personal agenda was, wasn’t to help, but to hurt. And to use every individual for their own gain. That’s what he did—Stewart, he bought mansions all over the country, yachts, you know what I mean, travels, he got planes.

Williams: [00:57:35] So, this is what, you know—this is what I got involved in, thinking that this was—while looking for something.

Lewis: Yeah.

Williams: Looking for family, right?

Lewis: Mm-Hmmmm. That was your home with them.

Williams: Or, I wanted to make that my—it wasn’t my home. But I wanted to make—maybe I wanted to make something my home. I—but that wasn’t—but the way that it happened was that I was misled. I was… I was young, and I was targeted by older brothers and sisters in the church. Because that’s what they do, they go after the younger ones because they’re stronger and they can produce more. And that’s what that was. So I understand what that was. But the problem is, is that—if I, plus I went off my medications. “Oh no, you got Jesus now. You don’t need that.” So go figure. I’m running on my own energy, on my own impulses, listening to other people, but not making decisions for myself. If Jim said do it, that means you do it. So, that’s how I got jammed up.

Williams: But so I—I left. I left the church, and emotionally I was messed up, because I always—because I was brainwashed. And I couldn’t erase going to hell, or this is where I have to be. So every time I left—so when I left The Fellowship, and I come back to Baltimore, I feel guilty. Like, I’m just playing games, I’m not for real with God. I got to be there to be for real with God, let me go back! And that’s what I would do, I would go back and forth for years in between. And then finally, I got so pissed off that I was like, “Fuck you. I ain’t coming back. The way you treat me? No, I ain’t coming back.” And I finally was—I think around, like 1986 was when I really put my foot down.

Lewis: [01:00:02] How old were you then?

Williams: About twenty, I guess. Nineteen, twenty. Yep. But I just want—so you know, but I think that was a—that’s an important piece of my life. And I want you to see how I became the way I am, through the organizing and through… It was because of religion that I had that kind of zealousness, that kind of outreach that like, nothing stopped me, like, “I’m going to get you to pray with me, and I’m going to lead you to Jesus.” That type of thing.

Lewis: I remember you told me a long time ago that you learned how to do outreach with the cult.

Williams: Mm-Hmmmm.

Lewis: And we had a couple other Picture the Homeless members that had spent some time with them, too.

Williams: Yeah.

Lewis: Like, Bruce said he did, and Shawn.

Williams: Shawn, yeah.

Lewis: [01:01:04] But I want to—I want to stay in this time period of when you’re young in Baltimore. If you could kind of describe what Baltimore was like then?

Williams: Well, I think one of the major things for me, going to school—was the level of violence. We always had access to guns, through a friend or somebody else. So, I think one of the… So, you know—we would see chalk lines around the neighborhood, in the alleys. You know, back then, someone got murdered, they would draw the chalk line, and it would stay there. They wouldn’t—until it rained, then it would go away. But other than that, that chalk line stayed there.

Lewis: Wow.

Williams: That’s what they used to do here in Baltimore. If there was a murder on that corner, they would draw the chalk line of the person there, with the puddle of blood there and leave it there, and wouldn’t wash it down. They would just leave it there until it rained.

Lewis: Dang.

Williams: [01:02:19] So we always—so, I used to always walk through the alleys. I used to—we used to travel through the alleys of Baltimore. So, when we traveled through the alleys of Baltimore, guess what we would see? A puddle of blood and chalk! A chalk line of a body! That’s what we saw. That was my introduction to my neighborhood. This what—you know, “Oh yeah! I know who that was. Oh, that was so-and-so that got stabbed to death, or shot.” So, even for it to hit home for me, was very young. I was in elementary school. I had passed from—I had graduated to sixth grade and moved to the—and went to the seventh grade. My best friend, Frankie Fayall, failed that year. I was dating his sister. We would fight all the time. Dorthena Fayall. They lived over on Homewood [Avenue].

Lewis: And the school? The name of the school?

Williams: Yes, right there near the school, yes.

Lewis: What was the school?

Williams: Cecil Elementary.

Lewis: Oh, okay.

Williams: The one I showed you.

Lewis: And the middle school?

Williams: Mm-Hmm?

Lewis: And then you went to middle school?

Williams: [01:03:38] Yeah, I went to junior—junior high school. It was elementary to the sixth grade. Then past the seventh grade to junior high. I went to Northern Parkway [Intermediate School]. So, when I graduated, I went to Northern Parkway. Frankie was changing, but—so we were friends, and we would hook school. Elementary school. We would actually hook elementary school [laughs] and hang out. And one day took me to his house and he said, “Anthony, check this out.” And he showed me this shotgun, his dad’s shotgun—shotgun in the closet. He goes, “You want to hold it?” I’m like, “No.” He goes, “Come on, check it out!” I said, “Nah Frankie, it’s all right. Nah, you know—I don’t want to mess with a gun.” And he goes… I said, “Nah, man.” He goes, “All right!” And I left.

Williams: [01:04:45] Three weeks later—no, about a month later, he does the same thing again. He invites this kid named Gabby, to his house—gives Gabby the gun. Then Gabby goes—lifts up the barrel and goes, “Think fast, Frankie.” Boom. Blew his face off. Closed coffin funeral. I didn’t go. I just kind of like sat on the curb and wept at the day of the funeral. [Pause] Frankie, he was a friend. We—I used to go to his house, I was dating his sister, we would dance, you know for... I would go to her birthday party. She always invited me to her birthday party. I’d go to her birthday party, dance with her. We would fight like cats, you know. But we didn’t know what we was doing. That was the way we loved each other, I guess. Didn’t do anything else, but fight. I don’t even think we really kissed. [Laughs] Anyway, but she was beautiful. She had really like, Indian, coarse type hair, like long. Beautiful—she was gorgeous, wow... But yeah, Frankie—he had like curly hair, too, but African American. But I think they had some Indian blood in them. You would think something like Cherokee or something. But they were—because the way her hair was like—it wasn’t woolly like ours. It was—but yeah, I—I...

Williams: [01:06:31] So it was Frankie. Then it was another friend. Then it was another friend. Then it was another fiend. So, I decided, you know what? I’ve had it. I’m out of here. All my friends are dying around me. They’re being killed.

Lewis: And you’re in middle school.

Williams: Huh?

Lewis: You’re in middle school when all this is happening?

Williams: Yeah! My brother committing murder. I mean, it’s—I got suspended from school, and my social worker would come and pick me up, Miss Schneider. And say, “You know where I just came from, Anthony?” I said, “No.” “From court with your brother! He’s going to do life for murder! And look at me bringing you back to school.” They gave me a half a day because I was—they felt I couldn’t handle a full day of school. So, they would give me a half a day and give me a pass every day to go home. I only did the three subjects, that’s it, and went home.

Williams: [01:07:30] I was really out there, man. I was really—I didn’t know—I didn’t know, man. I just—uh, through all that, running away, and [pause] loss of life... Not understanding, really—any of it, psychologically. It was happening. I saw it happening. I felt it. But, I didn’t really understand it to where I could say to you—why did this happen to Frankie? I was smart enough to say no. How come Gabby couldn’t say no? Or, why would he bring somebody to his house, show him his father’s gun, and somebody playing around, not knowing that it’s loaded, shoots him with it?

Williams: [01:08:26] See, my foster father had guns, in a tackle box in the basement and I found them. And I would take the bullets out and put them back in. Take the bullets out and put them back. But I would never take the gun out of the house, or take it out of the basement. But I would go down there and play in the tackle box, with the gun. So, I understood the seriousness of a gun. I did understand that part—that you don’t point a gun at anybody. But I just was intrigued with taking the bullets out and putting them back in. [Smiles] Then later of course, when I went back, when I was a little older, he had the gun in the house under the chair. So, when you come in, you sit right on the gun. You don’t even know you’re sitting on a gun. [Laughs]

Lewis: Your foster father?

Williams: Yeah. And I said, “Dad, don’t you know that…” He goes, “Oh, yeah Anthony. That’s okay. I always keep it there. It’s all right. I always keep it there.” It was a .38 revolver, six shooter—big one. But so…

Williams: [01:09:41] So yeah, I mean—I think throughout the stabbings, the killings… It just did so much to me that I had to get away, and escape into something that wasn’t that. And I thought that—and I think the religion was—because I could talk about that, you know. And they would say, “Well, it’s because of sin that these things happen, and it’s because of God, and it’s because of wrongdoing. It’s because of the devil.” So, they had a way of taking your story, right? And using it to benefit their agenda.

Lewis: Mm-Hmmmm. And they—they provided you

Williams: All the resources.

Lewis: with a narrative, with an explanation.

Williams: And also, the resources. You had food. You had shelter. You didn’t have to worry about food. You had to worry about work. We all lived together. They had houses up and down the East Coast, Canada. They had money. And they—this how they would recruit young people. That’s what they did. They would go, “You should talk to the young people, because they’re basically vulnerable. Like, “they’re lambs.” That’s the word they used. “You need to go after the lambs. Jesus always took care of the lambs.” So, guess what that was? I was a lamb. I was considered a lamb when I got led to Jesus. And that’s how I got converted.

Williams: [01:11:32] They—because they used Biblical language to match physical and spiritual language. So, when you’re looking at physical things, you look at them, first from the physical aspect, then the spiritual aspect. And that’s when you start looking at things a certain way. Not the way that’s black and white. But like, it gets distorted. I could take this, but then I won’t—I could do this, but I won’t do that. Or, I would take in this, but won’t take in that. Or, if I’m not right with God then I’m guilty, and I’m always on the outside, until I make things right with God and then I’m all right. So, I was always taught that it’s either you’re right with God, or you’re not right with God. If you’re not right with God, you don’t pray. You don’t play games. You don’t—if you’re going to go to Hell, you go to Hell in style. So, every time I left the church, it was a death wish for me. Because, I knew that I can’t play games with my life. [Mimics voices from the church] I—I was exposed to the truth! I was exposed to God!

Lewis: [Laughs] Jesus.

Williams: [01:13:15] And that’s it! I can’t—I can’t go back. I will die and go to hell. But I won’t play games with Jesus. It’s distorted.

Lewis: So you came back to Baltimore when you were twenty, when you finally

Williams: Yeah.

Lewis: left the church. And what was your life like then, when you came back?

Williams: I could never—I couldn’t stay put. I had friends that have businesses in New York, that left the church that I did a little work with before. And every time I came back to Baltimore—again, I just—the violence. The guns and access to guns. I remember having this landscaping job out on York Road, and a guy was smoking weed. We’d go in the office and he—here we go. Guy pulls out a gun. And he’s like—wants to play with the gun, wants to play with guns now, wants to point them. I said, “Come on, man.” You know what I mean? Like, seriously. This is—you know, it’s like, it just kept happening. Like, why is this happening? I don’t need to play with guns to have fun with you, guy! You know, or to party. Why do we got to whip out the guns? What is this? Is this trying to impress me? That’s not impressing me at all, man! I got no [unclear] as they are. It’s not impressing to me, just because you—you know, I was always around guns.

Williams: [01:14:48] Unfortunately, I was even playing with them as a kid, and thank God I didn’t blow my own brains out, to be for real. Because I didn’t read no—I was experimenting myself with taking the bullets, putting them in, taking them out. I didn’t know what I was doing. Nobody showed me how to do that. I figured it out on my own, and that was dangerous. But yeah, so that was—so, this is a long history of violence in Baltimore. It’s—it has, you know—it just went into a whole, nother level with our young people that…

Williams: [01:15:25] Like, I was on a train on my way to work. There’s about six young—young brothers on the train. [Pause] They’re scary. They were scary. Not for me, because I look at things a certain way, and if they were to came over to me, I would say, “Hey, you don’t want any of this. Just keep it moving. You know, don’t—I’m not going to play with you. I’m not going to—I’m not here for that. I’m on my way to work. I have my life. Don’t play with me. Just go somewhere else.”

Williams: [01:16:07] But what they do is they—they intimidate people to the point—and you know—it’s not really innocent anymore, because it’s a group of them. Because it’s a group of them, because it’s a group of them, and that’s what puts people in panic, you know? It’s not like it’s one or two guys drunk on the train making jokes, you know what I’m saying? When you have six kids, and very aggressive, and throwing stuff around, and bumping into each other, and moving ways, and you’ve got to watch, and like—really... It’s—it can be unnerving. And it’s—and, you know I, I can’t—I don’t want to hurt young people. I don’t want to fall into that position that I had to. But they’re dangerous. And they are—you know, I try to build bridges with the ones that I can. I try to tell them, “Look, I’ve been there. I’ve done that, and it just gave me more grief than I needed.” But when they get together in a group, that’s when you have problems. If you catch them by themselves, if you can get two of them together and change their mind, like I did—which I’ll talk about later. In the detox with the Bloods, when I was in New York. So when you can get to them, in a way where they can listen to you, then that’s good. But if you got five or six of them, don’t even bother! You’re asking for trouble. Because they want to impress each other.

Williams: [01:17:56] I remember across the street from where I live I was—I got in an argument with this young kid. Because he wanted to show off in front of his girlfriend. He goes—so he had a cup on the counter, and I put a bag on the counter. He goes, “Get that dirty fucking bag away from my…” And I’m like, “It’s not dirty, man. I’m just…” You know what I’m saying? I’m like… So, now he wants to get riled. And so, again, I have to fall back. I have to say, “You know what? Let him look good. Let him impress the girl. Let me just go, and go home, and stomach that one. It’s tough. It’s tough out here, Lynn. I mean, it’s really tough. And it’s—and it’s… You know, when you deal with—aw man... We got young people. But then you have the homeless folks, that—boy. It’s work.

Williams: [01:19:11] We got work. And the work is—people don’t want to do it! They do not want to deal with people, no more! They just—the city, they don’t—they would do anything not to do the right thing, to help people in Baltimore City.

Lewis: What would the right thing involve?

Williams: The right thing would be—do what your job that you get, is to do. If you’re getting money for homeless services and programs, provide those services and programs. Right? If it’s an issue with housing, and if HUD [United States Department of Housing and Urban Development] is giving the city money for rapid rehousing, then get rid of these stupid-ass definitions, and start housing people, and stop holding them hostage. Because that’s what all this is doing. This whole chronic homeless thing—I got housing because I was chronically homeless. But what if I wasn’t chronically homeless?

Lewis: Right.

Williams: And then I was just—you know, homeless?

Lewis: You didn’t have enough days to qualify.

Williams: Right, you understand.

Lewis: Yeah.

Williams: [01:20:35] And so I tell them, “Look! Coordinated Access is a problem. Because you’re only going to house chronically homeless people. Anybody that comes through your system isn’t going to get housed. They’ll be found ineligible. We got to do something about that! So, you know, like—just the stuff that I’m dealing with, like with the Mayor’s office, with Coordinated Access, with—you know what I mean? I have the—we have to write the Continuum of Care of Baltimore City, and explain how and why Coordinated Access isn’t the way we’re going to house people in this city. Because you’re finding too many people ineligible. They’re not going to be found eligible. What’s—their job is, is for you—is to find a way for you to prove—they have to figure out if your story is exact and true and then rate it—rate it! And you can’t—and what they tell you is you can’t fake it. You’ve got to rate it the right way, or you’re in fraud.

Williams: [01:21:52] I mean, I went through the training. I went and sat through the trainings. You know, I do all that. Okay? I went. My group went. We went to the Coordinated Access training for the managers, and sat there, and observed. We said, “We want to come and observe. We’re not going to talk. We’re just going to watch. And then we’ll let you know later how we felt.” Aw man, it was terrible. I mean, one of the women said, “This is not good.” She just saw it so clearly. She goes, “Man, this is not good. We’ve got to do something about that. This is not going to—no, no.” So they know.

Lewis: [01:22:53] They only have a certain number of spots. So they’re going to do everything they can to keep people out. They’re gatekeepers, right?

Williams: Yeah.

Lewis: So earlier you had said—earlier when we saw each other earlier, and you were talking about being happy to be back in Baltimore. So, earlier in this interview you talked about Baltimore—that there being a lot of pain. But you’re happy to be back.

Williams: Mm-Hmmmm.

Lewis: And we’ve known each other almost twenty years. And, I know you well enough, I would say, to be able to say you look really happy. And so, what is that balance? And you had balance on the paper you showed me. [Laughter] What is the—Baltimore’s a lot of pain and yet, here’s Anthony back here, and you’re happy.

Williams: Yeah. [Long pause] You don’t really know how much power you have, you really don’t know how much power you have, until you really discover it, and you use it, and you see it working. And it’s not only working for you, but it’s also working for other people. So, my transition from homelessness in Baltimore as an adult, has also helped me to help thousands of other people. That’s why I’m happy, because I can make a difference. I was able to make a difference in ways people didn’t even realize I did! Because I don’t toot my horn. But the whole thing with the men’s overflow with the rotten mats, they all got cots now. That’s because I talked to the deputy mayor and said, “This is wrong.” Bedbugs and dirty mats—ten years they’re dirty! These mats been there for ten years! You’ve got them sleeping on them with blankets? Come on. You wash the blankets, but you still got them sleeping on dirty mats. Is that clean? What the hell you doing?

Williams: [01:24:56] And then, the doors off the bathrooms. What kind of shit is that? I mean, come on. You can have a stall. There’s ways to deal with overdosing and stuff. There’s ways to handle that. Either have a monitor at the door or say, “Look, it’s time for you to get out of there. You’ve been in there too long. Are you all right?” Like they used to do in the shelters in New York. They’d knock on the door, “Boom, boom. Security. Hey, hey, hey, you’ve been in there too long. Time to go. “You know what I mean?

Williams: [01:25:21] But so, I think I’m happy because—because I’m able to do what’s needed for myself, and for other people. And I think it just all came to a head, in one year. You know, I was able to accomplish so much in 2015, and being able to address my problems... I was able to do a lot of work, inside work, and organizing work, and outside work. So, I was able to do the inside work for myself, which gave me the confidence to do the outside work. But I couldn’t have been able to do the work I’m doing now—I wouldn’t have been able to do the work I’m doing now if I hadn’t did the work on the inside, for me.

Williams: [01:26:25] I was able to work on myself and have the confidence and the know-how to say, “Hey, I don’t care what you say. This isn’t right. And I know it isn’t right. If I know it isn’t right, I’m going to tell you that it’s not right.” Right? And I can understand it, and I can show you how to change it. And we’ve got power to change it. But you have to help me. You have to work with me. You have to be with me. We can do this.

Williams: [01:26:54] But it’s a matter of—you know, when I first addressed the Continuum of Care, I gave them hell. Because they wanted to privatize. They wanted to get United Way to—instead of the city—to run the Continuum of Care. They were going to give them this whole RFP [request for proposal]. And I went against it. And they were mad at me. But I told them, I said, “Look, I’ve done the Continuum of Care. I know a person that helped write it!” I said, “I know that this isn’t the way to go! I know it isn’t. Let the city take the responsibility! Don’t privatize it! Let—we can hold the city accountable. If you privatize it, we can’t! I’d rather”

Lewis: That’s brilliant.

Williams: hold a city accountable, than to give it to the United Way!”

Lewis: Right. And the city’s causing all the homelessness.

Williams: Right.

Lewis: In a lot of ways. So, why should United Way come with a little mop and not clean up?