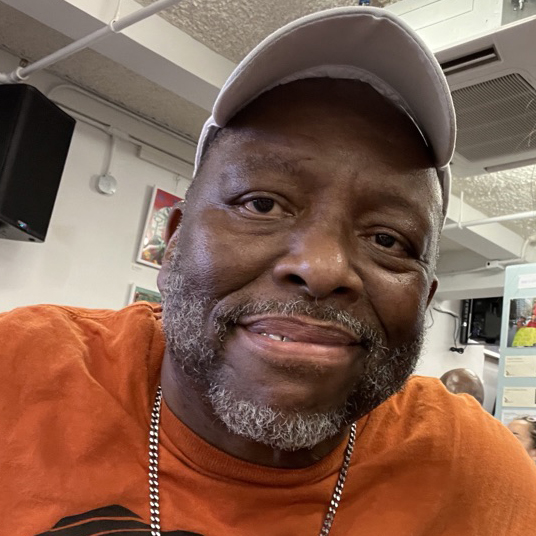

Rob Robinson

In this compelling Oral History, Rob Robinson shares his transformative journey from being a student-athlete to experiencing homelessness, and ultimately becoming a prominent voice in housing justice advocacy in New York City and beyond. The conversation begins with Rob’s upbringing in Freeport, Long Island, where he and his family faced challenges stemming from redlining and school district discrimination. Despite these obstacles, Rob became an honor roll student and earned an athletic scholarship to study business in Restaurant Hotel Management in Maryland. After graduating, he moved to New York City's Lower East Side.

Rob discusses his career shift from the restaurant industry to an Information Technology job in Miami, Florida, and the life-changing experience of being let go after four months, which led to homelessness in both Miami and New York City. It was during this period of struggle that Rob began studying gentrification and connected with the grassroots organization Picture the Homeless, marking the start of his organizing work.

The interview offers a deep exploration of Rob’s evolution as a housing justice advocate, beginning with his belief in the importance of sharing personal stories to dispel the myth that homelessness is a personal failing, rather than a systemic issue. He reflects on his early experiences with Picture the Homeless, including a transformative trip to Hungary in 2009, where he realized the power of storytelling in the fight for housing rights.

Rob also recounts his first meeting with renowned geographer Neil Smith at Columbia University, describing how their relationship influenced his activism. A key moment occurred during a conference at The New School, where Rob challenged academics to engage more directly with community education and to uphold Smith’s legacy.

His activism expanded through his involvement with "Take Back the Land," a group focused on relocating families evicted during the foreclosure crisis. He discusses his collaboration with the Brazilian group MAB and the importance of Community Land Trusts in reclaiming land for marginalized communities. Rob highlights significant victories, such as preventing the eviction of Catherine Lennon in Rochester, NY, and reflects on the challenges of increased public attention that led him to step back from Picture the Homeless.

The interview touches on Rob’s collaboration with Kali Akuno and Max Remo to establish a national Take Back the Land network, their work with the Occupy Movement, and the increasing adoption of the Community Land Trust model. He also shares insights from a reading group centered on Henri Lefebvre’s "Right to the City" and the intellectual growth that took place within the Brecht Forum.

As the discussion progresses, Rob addresses the tensions and divisions within housing justice groups and his decision to take a more international approach to advocacy. He explains his current work with the Cooper Square Community Land Trust, where he focuses on implementing popular political education. Rob emphasizes the immense responsibility of creating a Community Land Trust, underscoring the need for resilience, selflessness, and dedication.

Gentrification

Homelessness

Housing Organizing

Peter Marcuse

Neil Smith

Tom Angotti

David Harvey

Max Ramo

Catherine Lennon

Miguel Robles Durán

Kali Akuno

NESRI [National Economic and Social Rights Initiative]

Picture the Homeless

Take Back The Land

International Human Rights Law

Brazilian Constitution

City Life / Vida Urbana

Brooklyn, New York

Freeport, Long Island

Lower East Side/Alphabet City

Sheraton Hotel

Tavern on the Green

Maryland

Miami, Florida

Szeged, Hungary

Medellín, Colombia

Brazil

Rochester, New York

Boston, Massachusetts

Toledo, Ohio

Why Hunger?

MAB [Movement of People Affected by Dams]

MST [Landless Workers Movement]

Occupy Our Homes

| time | description |

|---|---|

| 00:00:00 | About Rob’s background and where he grew up. Rob describes several challenges his family faced when buying a house in Freeport, Long Island, including discrimination, redlining, and worrying about mortgage payments. |

| 00:03:02 | Rob reminisces about the world he grew up in in comparison with the world we live in nowadays. He describes differences in communal life within the neighborhood, and changes in the cost of living while building a family. |

| 00:04:40 | Rob speaks about how his family would travel from Brooklyn to Freeport in order to visit them. He also shares about his experiences traveling to the South during Jewish holidays and Spring break to South Carolina and Florida. |

| 00:05:55 | About how people living in the suburbs want to live “where the action is” – New York City. Rob speaks about his first apartment in New York City which was in the Lower East Side. |

| 00:06:40 | Rob speaks about his scholarship to study in Maryland and also about injuries as a student athlete. In this section Rob shares with us some of the challenges he experienced regarding education and racial prejudice, particularly with qualifying tests. |

| 00:10:30 | About Rob moving to New York City after completing college with a Business degree in Restaurant Hotel Management. Rob shares with us some of the positions he held as executive chefs in some of the restaurants and hotels in the city. |

| 00:11:51 | Rob reminisces about how different the Lower East Side was when he was living there compared to now. He speaks about how “Alphabet City” was a neglected neighborhood that had landlord abandonment and drug abuse issues. |

| 00:13:56 | The start of Rob’s “transformation”. Rob was told by doctors that the restaurant business was hurting his leg and that he needed to get into a new brand of work. Rob got a job in ADP Automatic Data Processing, which is what began the shift in his mentality. |

| 00:17:13 | About how even though Rob was asked to move to Miami by ADP and became their software expert, he still was let go by the company. After running out of resources, Rob experienced homelessness both in Miami and in New York City. This shifted Rob’s mindset about these companies, the economy, and housing. |

| 00:19:39 | Rob starts studying the phenomena of gentrification while being homeless in Miami and upon returning to New York City. This led him to develop his own theory of homelessness and criminalization and how it is a structural problem and not an individual one. |

| 00:21:39 | Rob speaks about the importance of telling his own story so people won’t internalize their struggle as their own fault, instead of a societal issue. |

| 00:22:35 | First contacts with the organizing group Picture the Homeless. Rob explains how a trip to Hungary in 2009 with this group showed the importance of sharing stories. |

| 00:26:55 | About Rob’s first encounter with Neil Smith in a panel discussion in Columbia University. Rob speaks about how Smith took interest in Rob’s theory and how they developed a relationship after. |

| 00:28:29 | Rob speaks about a conference in The New School in which he challenged the academics in the meeting to “pick up Neil’s legacy” and engage with communal education in a more direct way. Rob speaks about how important it is to “shake off” the label of homelessness. |

| 00:30:35 | Rob speaks about another group he was very active with called Take Back the Land. This group was mostly dedicated to relocating families into houses they were evicted from during the foreclosure crisis. While speaking with this group, he started discussing the importance of Community Land Trusts with help from a Brazilian group called MAB. |

| 00:33:50 | Rob speaks about the importance of going to Brazil to meet with MAB and the Landless Workers Movement MST. |

| 00:34:48 | About some of the battles Rob and Take Back the Land had with Bank of America, particularly how they did win and stop the eviction of Catherine Lennon in Rochester, NY. |

| 00:37:30 | About the challenges of handling the attention certain social justice groups receive. Rob describes that that was one of the things that started to make him drift a little bit away from Picture the Homeless. |

| 00:39:09 | About how Kali Akuno, Max Remo and Rob Robinson came up with the idea of making Take Back the Land a national umbrella organization with local chapters in all of the US. Rob speaks about some of the actions they did in 2010, and how they also worked with the Occupy Movement. |

| 00:43:00 | About how the movement became admired because it counted with support from respected academics. Rob also shares about how the Community Land Trust model became the go-to for different organizing groups. |

| 00:44:50 | Rob speaks about a reading group created around Henri Lefebvre’s idea of a Right to the City and how certain ideas were developed within the Brecht forum. |

| 00:47:14 | Rob explains how different housing groups fractured and how he wanted to be more behind-the-scenes. He speaks about different tensions and fractions between these groups and how this made him have more of an international scope. |

| 00:49:46 | About Rob’s current role in the Cooper Square Community Land Trust. Rob shares about what he wants to implement with the organization - popular political education. |

| 00:53:41 | Rob explains how much of a heavy burden it is to create a Community Land Trust. Rob goes into the importance of commitment, organizing, being resilient, and selflessness when carrying out this work. |

| 00:56:00 | Regarding the recent shift of mentality and being more open towards new forms of relating to land. Rob is skeptical towards the US’ willingness to learn and emulate international efforts. |

| 00:59:50 | Rob explains the importance of popular political education and the importance of interdisciplinarity like law, economics, and urban planning, to bring about social change. |

| 01:02:20 | To conclude the interview, Rob gives a word of advice to the new generation of activists and organizers. |

Gabriela: Hello. Today is October 25, 2023, and I'm here at The New School with Rob Robinson. Thank you, Rob, for having this conversation with me.

Rob: Thank you for having me.

Gabriela: So tell me, where are you from and where were you born?

Rob: So I was actually born in Brooklyn, New York, but my family moved to Long island in the early sixties. We were, you know, one of the families amongst our clan to get out of the inner city and move out to suburbia, right. Even though there were challenges there. And as I look back, I realize it's helped shape the way I think now, right.

So my dad... I grew up in Freeport, Long Island, a seaside community.

We moved out there when I was five years old. So all my education came from Long island. And I'll talk a little bit more about education because it shifted once I got to high school.

But it was a challenge, right? My mom and dad found this house in Freeport, but they were discriminated against by a broker. When they went to see it, and the broker saw them, they were told: "there's somebody that already put a big down payment on the house. Looks like they're going to take it". So my parents decided that was the house they wanted. They didn't believe the broker and one of my dad's friends, who was white, approached the broker and made an appointment to come out and see the house. And the broker asked him if he wanted to put a down payment on the house.

And they basically had him at that point. So, we got the house. But I also, you know, as I reflect, I look back and say: "okay, I understand predatory lending now", because my dad, I didn't see him as a kid. He worked hard. He worked in the restaurant business.

He worked 18 hours a day. And when he came home for dinner, everything was about the mortgage,

the mortgage payment, the mortgage payment. So it was a little bit overwhelming, you know, even though he managed to do something that a lot of others didn't do, get his family out of the inner city, and even though redlining and all these other things that existed, he was able to fight through that and settle us on Long island.

Gabriela: Yeah. So this was the time of, like, everyone is moving out, right? Yeah. Just a few families.

Rob: Yeah. Early sixties. Early sixties. We were at the time... there were two other black families on the block, out of seven, right. We had white neighbors, a French woman and an Italian man. The Italian man worked for Pan Am Airlines. So as kids growing up with five brothers and sisters, we had a house full of Pan Am toys.

You know, he would always bring us different toys. So we sort of loved our neighbor, and it also makes me reflect on how times have changed

because her name was Yubi and her mom had passed away in like 63, 64. I may be off by the years, but I remember every family on the block getting dressed up, lining up in their cars, and we went out, like, in a procession out to what was called Idlewild Airport at the time now JFK. And we actually saw her off to France. We drove onto the Tarmac and waved goodbye. Right. So my.. How times have changed. I often think about some of the things that went on then. I'm like, this world has changed.

But, yeah, my upbringing was there, on Long island, [it's a] fishing community, so I spent a lot of time by the water, which is my attraction now. I love being by the shore. Freeport is a south Shore community in Nassau county, [a] working class community. So dad worked in the restaurant business. Mom didn't work when we were growing up.

She was a mom, but things were affordable then. Right. You could do that then. You can't do it now. It's impossible. It's next to impossible to do now. So, you know, I had an upbringing that I reflect on a lot to try to connect threads through what is happening now. And history as I was taught it and history as I experienced it, right. Which.... Those two things can be totally different. You know, sometimes when you're taught history from a textbook, that's not what you experience in life. And I think being able to articulate my own lived experiences, I think is important.

Gabriela: And during that time, did you travel to the city, or were you most...

Rob: Not much in the early days. Most of our family lived in Brooklyn, our immediate relatives lived in Brooklyn. So they would come out there. It was like, big deal to come out to Long island to visit us.

So there were these big Sunday dinners. and, you know, your aunts and uncles and your cousins would come out... We didn't do much traveling. [Well] We did travel. So dad always took us on Easter and Passover vacation.

He worked in the Kosher restaurant and deli business. So our traveling came in the later years, probably the mid sixties, where we would travel south every year. During spring break, we'd visit my mother's family in South Carolina and my dad's family in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. So that was the extent of traveling... As I grew as a youth but into my teens yeah, there was travel into the city. Then it was, you get on the Long island railroad, it's a big deal to come into the city, right. Like you're this teenager going to experience New York City. So it was cool.

Gabriela: I can imagine. And when was the time that you moved to the city?

Rob: So there was... Every young person growing up in suburbia... I shouldn't say "every young person", that might be wrong of me, but I think a majority of young people wanted to go where quote, unquote, "the action is" right, and the action is in the city. Suburbia is dead. Like [in] my neighborhood, you could hear crickets, after 07:00, especially in the summer. That's quiet, right? So you couldn't wait to get into the city. So I first moved into the city after graduating college in the early eighties. I lived on the Lower East Side, which turns out to be a place of learning for me and connecting, you know, some of those threads that I talked about, but it was interesting.

I went to the University of Maryland on a scholarship to play football. Injured my leg, but I should back up. I injured my leg every year of high school. So 10th, 11th, and 12th grade, I broke or fractured my hip, but I still got a scholarship to go to Maryland.

So I was good at what I was doing. But I think it's also important because I learned about challenges with respect to education. Again, more threads. So, while we lived in Freeport, we lived in a school district that was... That wasn't up to par, right. So my parents decided to buy a house in what was then known as the Five Towns, a heavily populated Jewish area on the south shore of Nassau county, which encompassed Hewlett, Woodmere, Cedarhurst, Lawrence, and Inwood.

And the school district there, was comprised of a 98% Jewish population, 1% black, 1% Italian, rated one of the highest school districts on the island. And, I ended up going to high school there. That's where I went to high school. And then my brothers and sisters followed. So we got a pretty good high school education once we got out of the area.

But, I think about some challenges and I think about racial discrimination, because when my parents put me in that school, and I was the first one, I had an older sister, but she had left home at an early age. She got married at a young age, so I was the oldest left at home. But the guidance counselor in the new school district wanted me to take qualifying tests because I came from this bad school district, and it kind of annoyed me. My parents didn't want to make trouble. They were suggesting that I just sit down and take the test.

So I took the test, and I did well, and I got placed well. But I also wanted to prove... and this is probably... people ask me where, where my inkling for social justice comes from. And maybe this was part of it. Her name was Miss Silver. And I remember getting my very first report card, which was an honor roll report card, and I would go into her office and I take the report card and I throw it on her desk.

"Who needs to take remedial courses? Not me". You know, and I did that for the next three times I got a report card until the principal interceded and said: "you need to stop this or we're going to suspend you. We'll call your parents". But it was, you know, it had angered me. Right? Like, you're going to judge me because I came from somewhere else. Not that, you know, you. You wouldn't allow me to fit in. You don't know what my aptitude is, right? So you're just going to judge me because I came from somewhere. So that kind of bothered me, and it sort of put a chip on my shoulder, and it's something I carried for a long time. Yeah.

So that was... Basically, I hurt my leg in Maryland my very freshman year. But the one thing my father is—Maryland would have guarantee a full 4-year education. ... My dad had an 8th grade education. [My] Mom had a 10th grade education. I was the first one to graduate high school and college in my family.

And the one thing that my dad said [to] Jerry Claiborne, the coach who was recruiting me, [he] said [to him]: "if he gets hurt, he has to get a four year ride[Xavier Mo3] . Otherwise I'm not signing the document". So, you know, I give my dad some credit for that. He wasn't an educated man, but he wanted to see that his child got something out of it. So he was very clear with the coach that, kn [he had] to sign this four year agreement, which, you know, a lot of people were surprised at.

But it did happen. So I ended up, once I graduated college, I decided I wanted to live in the city. I graduated with a Business degree in Restaurant Hotel Management. And for a number of years, I worked at some of the nicest restaurants in New York, Tavern on the Green, Sheraton Hotels... At one time, Sheraton had seven hotels here. So there was a time where I held Executive Banquet Chef title at Tavern on the Green and

Assistant Executive Banquet chef at Sheraton Hotels, right. So [I'm] young and, you know, living in the city, making a lot of money, not having a care in the world. But I, that proved to be kind of foolish now that I look back on it. I can criticize myself [because] I wasn't thinking about the future. I was thinking about now. So kind of problematic.

Gabriela: Yeah.So you being very smart, getting a college degree, you know, and then coming to the city. That was always in your radar.

Rob: Yes.

Gabriela: And you landed in the Lower East Side.

Rob: The Lower East Side. It was the only place that was affordable. And at the time, it's kind of funny when I reflect and look back now. So I lived in what they call Alphabet City. I lived on Fourth street between avenues B and C.

A lot of activities were going on, not necessarily legal. And, you know, it's just: "out of sight, out of mind". You, just survived, right. I would sometimes come home at 01:00 in the morning in a taxi, and there might be illicit activity going on in the street. The drug dealers would open the door. "Oh, that's the guy with the bad leg. “How you doing, sir”? They would, hold the door." [laughs] You know, it was kind of humorous at one time, but, you know, you learn to "hear no evil, see no evil, speak no evil", right? So I survived in that area for about seven years.

Gabriela: So around this time there was a lot of poverty.

Rob: Oh, it was... So I really, I got to witness it. I wasn't working in it, but I was seeing it and touching it. So... During that time, there was a lot of abandonment on the Lower East Side. Vacant buildings

where landlords just stepped away and left them. And, you know, maybe they became what we called -shooting galleries- with drug addicts, selling and doing drugs. So it was, it was somewhat of a depressed area, I could say that. But I wasn't, I wasn't attuned to social injustice at the time. Right? I was... I was thinking differently. I was thinking in capitalist terms, right? I want to be a landlord. I want to get some of these properties and rent them out and make a lot of money, you know? I think that was a learning experience to reflect on how you once thought. And then after what I like to call the transformation in my life, how I look back and reflect upon those days.

Gabriela: What was the turning point for you so that you started being more aware?

Rob: So it was actually... So, Doctors eventually told me:

"The restaurant business is damaging my leg. You're not going to withstand being on your feet constantly, so you have to get into some different type of work". So one of my dad's friends ran an insurance company, an assigned risk auto insurance company, on Long Island. I went to work for him for a little while. And then I got a job with ADP, Automatic Data Processing, the payroll company.

I worked for them for 13 years, and that's where the transformation happened. I worked myself up from taking payrolls from mom and pop businesses over the phone and keying into what was called the CRT terminal at the time to becoming a project manager, overseeing this new piece of software that ADP said would move it into the new millennium. Looking back because of my willingness to work with customers and take their payrolls over the phone sometimes, I had one customer who would fly back and forth to Yemen, and he'd say:

"I got to get my payroll in". And some of the other reps. Well, [they'd say]: "I can't just take the numbers over the phone. You got to you got to be in the, oh, yada, yada, yada. And I would just accommodate him. I would just take it, right? He'd give me names and I'd go back and look up the information and key it in the computer

But I was on these terminals, and I didn't have good typing skills, but I could hit certain keys and bring the system down, the mainframe computer system of ADP. And people used to laugh at me and say: "Oh, yeah, yeah, you're full of it." But I could, I knew when I typed..., if I hit Alt control and the Insert key, trying to type, all of a sudden the computer room would come in and say: "we're going to be down for a few minutes". So it became like a running joke. "Oh, Rob brought the system down. Rob brought the system down."

Until one day the General Manager had, like, corporate execs come and he wanted to try to make fun of me. So he brings, like, the CEO of the company and this other high level execs to my test.

"Okay, you can bring the system down. Show us." So I open up that key fast system, and I hit the Alt Control and Insert key. And in two minutes, the guys were coming out of the computer room saying: "we're going to be down for a few minutes". Then all of a sudden it was like: "come with us. Come up front, we want to talk to you". [laughs] And they ended up sending me to a school to learn IT [Information Technology] in their system and, you know, understand the language.

So they bought this piece of software. It was a call center based piece of software that at the time, in the early days of computers, if you bought a piece of off the shelf software and you wanted to change it, you had to get permission from the company to change it, and then you had to find the company that could put your labels on it. So in other words, ADP labels. So I worked through that transition, [I] became like the expert on this piece of software. I was asked by ADP to move to Miami in March 2001.

Very little notice. I was given a $10,000 relocation fee. Three weeks, three months in a hotel and a car to drive for three months. At the end of three months, or at the beginning of the fourth month, I was called into the General Manager's office [and was told]: "there's no more money in the budget for your position. We're going to have to let you go".

That was shocking to me, but that started what I call the transformation, because it made me look at this Fortune 500 company differently, realizing that they don't really care about people, right? They cared about whatever they can get out of you, and they'll dispose of you when they feel they're done with you. So that was a hard lesson. But then, you know, through that, I got severance pay. I had unemployment. After a year that ran out, I started to tap into a bank account --that ran out. Then 401K. Before you know it, I'm homeless on the streets of Miami,

and, spent two and a half years on the streets of Miami, found my way back to New York, and spent ten months in New York City homeless shelter. But I call that the transformation of Rob Robinson. Like, I started to see the world through a different lens. It looks different than it was explained to me, not only in schools and, you know, through education, but through family [too].

Like: "Okay, no, this is not the way it is. This is the way it is, right?" And, you know, I started to ask a lot of questions. I started these questions in Miami: "Why is it [that] people who are struggling with the same problem that I have look like me? So is it a predetermined path?" So while I was in Miami, I started noticing the construction of these luxury buildings that faced the beach. And they were right at the foot of the beach causeway that goes directly to the beach.

But that same causeway, when you were released from prison, they told you, you can stay underneath that bridge. So what a contrast and a contradiction of these two things face to face.

But those luxury towers would have bunting on them. That would say: "Condominiums coming soon for sale. Studios starting at $850,000. One Bedroom, 1.5 million dollars". Then over a period of time, the bunting changed to “For Lease, sign a two year lease and get two months rent free".

So I was like: "what is happening here? Why did this bunting change?" And I started hearing terms like gentrification and starting to understand. So a lot of my last days, probably the last six months, homeless in Miami, I would spend a couple hours every day in the library studying this thing called gentrification. And then when I came back to New York, I followed up the same way because I'd hear the same terms, and it helped me develop a theory,

which I say changed my life. And that theory was gentrification leads to displacement, which leads to homelessness, which leads to criminalization. It seemed like there was a predetermined path for some people, and most of those people looked like me, and it's something I still grapple with, right? And I try to get people to share their experiences, especially if it's a person of color who's going through this, right?

You know: "I want you to understand that this is something... this is a societal problem. It's not the problem that has been inflicted on you because you failed" right? But that's the way we label it. That's the narrative. And, in fact, it was those narratives that added to my transformation.

It made me angry when I would hear things like: "You're homeless because you don't want to work. You're homeless because you don't have an education. You're homeless because you have a chemical or an alcohol addiction. You're homeless because you have mental illness".

And I'm like, none of those things fit me. So I called it painting the issue with a broad brush. I would get so angry at those things and say "you're never going to touch me with that brush, and I'm going to find other people and get them to speak up like me". So I think that was the beginning of the transformation for me and this learning experience and thinking differently about the world and the world that I see.

Gabriela: So you start experiencing all this, starting in Miami and then here in New York. And I guess there were other people like you talking about how they got to the point.

Rob: But they weren't talking about it. So I found, I would be very open, and people would look at me strangely, like, you know, and especially women of color. There was a phrase they would always say: "why are you putting your business out like that?"

And to me, I needed to share the story because there were other people who experienced it, what I had, but they internalized it. And that's not right, but that's what society will make you do if you allow it, right? If you allow it. So it was important for me to open up and continually tell the story. And I still do it to this day, where 18 years, 20 years later, whatever it is, I still share the story because hopefully somebody is going to open up about this issue and realize that it's not [their] fault. And I learned that through a group called Picture the Homeless that I joined in organizing. [In] 2009 we got to go to Hungary.

Gabriela: Yeah, exactly. That is what I was going to ask you. Like, you have all these thoughts, and then how can you share these and take action? Was it through Picture the Homeless?

Rob: So a lot of it was through Picture the Homeless. In my days there, that trip to Hungary was special

because unbeknownst to me, a student from the CUNY Grad Center, who was from Hungary, had been following us around and wanted to create a similar organization in Hungary. Once Communism fell, a lot of housing was tied to work, and people lost their jobs in the Soviet Bloc countries, right?

So you started getting high numbers of homelessness, and it hit Hungary hard, people sleeping rough constantly. So in August 2009, four of us from Picture the Homeless got to go to Hungary, and there was one incident in particular... We do a series of talks and events, and it was one that really, really, I think, let me know that you need to constantly push people to share their story. So we're in a seaside community near the end of our 20 days in Hungary called Szeged, and I open up.

You know, I open up with a chant every morning. The Europeans weren't used to that, so sometimes they would stare at me. But I had two earpieces in my ear, one Hungarian to English and the other one English to Hungarian, right? So I start to talk about the societal causes of homelessness and the structural causes. And the translators say in my ear: "What? For 51 years, I've been blaming myself. Now this guy says it's not my fault". There was a guy in the audience who said he had been on the streets since he was in diapers for 51 years. So he carried that weight for 51 years. And it reminded me of how important it was to share stories, because at the end, he approached me, Gabriela, and he holds me, and he just starts shaking.

Rob: And as if he's getting some kind of energy from me.

Everybody kept saying, push him away. I'm like, no, I'm not pushing him away. Imagine him carrying that around for 51 years. Now all of a sudden, this guy comes and says: “it's not your fault.”

So it let me know two things. It let me know that I can push people to share their story and open up. Right. Once I do it, I've created a safe space, and they realize it's okay. But I used it in another way. Also, to me, storytelling was collecting data, and we often, in community we look at data as surveillance. And I said: “no, no, no. Now I have the data to prove our arguments that this is a societal issue”. So we need to understand that data can be used for or against. It's [about] your intention? For us, daa was used against, by the government or the people that are creating these narratives. To say that you failed. So it's been a mission of mine to talk about it in terms of data.

Some people look at me a little confused and try to understand it, but I think it's sinking in with people now. And I think the more you travel and the more you do it and create spaces, the more people realize it's okay to talk about it. “It's not my fault”, right? And I think that's what we need to help people shed. Is that whatever that is, that's over them that says: “it's your fault, you failed? No, the system failed you”. So it's been a mission of mine ever since. I call it the transformation.

But I think there's two interesting points of that transformation that I hope you'll allow me to talk about. One was that theory that I talked about. Gentrification leads to displacement, which leads to homelessness, and leads to criminalization. I was in a panel discussion at Columbia University in 2007 as a member of Picture The Homeless.

And to my right was Doctor Peter Marcuse. To his right was Brenda Stokely, a union organizer with the municipal workers union in New York. And to her right was Ed Ott, who at the time was the director of the Central Labor Council in New York. And they had me speak last. I'd never spoken publicly about these issues. [I’m] soaking wet from perspiration.

I am like sweating bullets, and I say what I have to say, and doctor Peter Marcuse puts his hand on my thigh and goes: “good job” to make me relax. But when I said: “gentrification leads to displacement, which leads to homelessness, which leads to criminalization”, Neil Smith was in the audience, and he stood up and said, say that again. And I repeated it. And then at the end of the conference, he came up to the table and said: "I want to know how you develop that theory. Let's meet for lunch." And, you know, I think that meeting went a long way. He brought me up to the grad center to lecture students.

I freaked out. I said, I can't lecture PhD students. I have an undergraduate degree. And he puts his face almost against mine, and he goes: “you taught me. You're going to teach my students”. So he made it clear to me that you don't need a piece of paper to be a teacher. If you have knowledge and you're willing to share, you're a teacher.

So it's something that has always sunk in. And then we had a conference here at The New School just at the start of the Design and Urban Ecologies and Theories of Urban Practice [programs]. And I had met Miguel [Robles-Durán] through Peter. Peter had sent me to meet Miguel and said: “He's an up and coming urban planner, Rob, I know you're fascinated with planners. Here's the guy I think is going to be the guy of the future”. So I reached out to Miguel, met him, and I came to that conference. And at one point at that conference, Miguel pulled me and a bunch of the different academics that were in the room

to hear me share my story about Neil. And I did it. And then I said: “I challenge you guys to pick up Neil's legacy”. And to Miguel's credit, you know, he did it.

Like, it was this interaction with community, collaboration, you know, a different way of teaching. So, it’s all part of that transformation for me. But it's a moment I like to look back and reflect and say: “you can be this homeless guy [and] be influential”, right? People look at you a certain way.

You might have that label, but I've always tried to… And this is something I've tried to impress upon Picture The Homeless members: “Don't let that label stick on you. It's not appealing”. Make sure it keeps falling off. And so every time I present myself, I want people to look at me like: “Okay, that was a homeless guy. Are you sure?”

Gabriela: I know that you have inspired so many students at all levels and faculty all over New York and beyond. So, tell me a little bit about this experience… because what you're telling me that you start these conversations with academics, but also being part of the Picture The Homeless, you started traveling and you start engaging with other organizations and other groups. And so tell me a little bit about that.

Rob: So probably, you know, I mentioned Hungary, but before that Hungary trip, several of us from Picture the Homeless, got to travel to Miami because there was work going on down there by a group called Take Back the Land.

And it was during 2008 , you know… We had the big foreclosure crisis, the economic crisis of 2008. And there was this work going on in Miami with this group that were finding houses that were foreclosed by a bank or government agency,

and they were breaking in them and moving the families back in there if they were evicted and defending their rights to being there using International Human Rights language. And quite frankly… four of us went down. We learned from that group. We participated in a move in, and I was inspired. And their leader was a gentleman by the name of Max Ramo. And Max was what I like to call an activist intellectual. He was a philosopher by schooling. We thought a lot. And, you know, Max and I started to think about how do we relate to land and housing differently.

And so the two of us, you know, did a series of events up and down the east coast. We were on PBS Now with Maria Hinonosa at the old Brecht forum. We did university events, but,

academia started to come towards us and really think about a different way of relating to land that was fundamental to us. Land and housing as a commodity was not going to work, right? And it's proven over a period of time that it didn't work.

So how do we change? What are the different models? And the model that sort of raised our eyebrows was the Community Land Trust model, right? You get land in perpetuity, and you can put cooperative housing on it, mutual housing, so many different ways you can go, but it's removing it from the market, thereby ensuring affordability over a long period of time. And that was a change, right? And it was a change even for me, because when I came out of shelter in New York, I was banging the table and saying: “we need more. We need more affordable housing. We need more affordable housing”. So it was that trip to Miami, and then it was a group out of Brazil

reaching out to Take Back the Land after that work. Well, they actually reached out to a group called “Why Hunger”, and it was a group called “MAB”, the Movement of People Affected by Dams in Brazil.

And they reached out to Why Hunger which is based here in New York. And Saulo Arujo from Brazil was their international organizer. And they said to Saulo… they had a YouTube video. “Saulo, do you know this guy? We always hear him talking about changing the fundamental relationship to land and housing. We want to meet him.” So Saulo laughs and Saulo goes: “Rob? Everybody knows Rob.” So at that time, they were using Skype, right? So Saulo had a Skype account that you bring many people on.

So Saulo goes: “Hold on a minute”. And then he brings me on their Skype call, and their eyes just lit up. And, they invited me to their Encuentro in Brazil. And for me… starting to learn from MAB and the Landless Workers Movement, the MST, and to study the Brazilian Constitution that says land has to serve a Social Function--- really changed the way I thought about our fundamental relationship to land. And I never looked back.

I always said: “you know, the CLT is the model to go”. We tried our best at Take Back the Land, to get some of the big banks to put houses into community land trusts, right? We did big protests against Bank of America. We would shut it down branches. But, you know, we were an African American organization with not much money. We had a big voice, right? But the bank said: “We're not giving those black folks that kind of power”, right? “We're not giving them these houses”. But we did actually fight Bank of America and won a house for a woman in Rochester, New York.

The Katherine Lennon story, which is well documented. She got evicted in March, March 2011, a very challenging eviction. We protected her house for about a week. Then the city of Rochester sent a SWAT team and 25 police cars to physically remove her. But we did something later that Spring called “Happy Mother's Day, Katherine Lennon”. And we did a very public movement. We called the press. We called the police and told them we were breaking into that house and moving her back in. And we did that. And it got a lot of press coverage, and the community bought into it. You know, there were great pictures of men in the community with a refrigerator on their back and people bringing, living room furniture and kitchen utensils. And it was just a whole community spirit.

We got approached by Rochester chief of police on that Sunday afternoon, and the chief of police told me and Ryan Acuff,

who was the leader of Take Back the Land, Rochester, [and the police asked]: “Do you know you're trespassing on private property?” So we said: “We understand where we are”. But then we asked him a question: “Why are you using public funds to defend private property? If Bank of America says this is private property, [why] are you using public money to defend it?” And the police chief scratched his head, told his men: “Come on, let's go”. And, you know, the story is that Kathrine lives in that house today with her eleven family members.

We got the house from Bank of America a couple of years later for a dollar. When they put her out, they wanted $50,000 in cash. We got it for a dollar… but it was just dragging their name through the mud and challenging them. And, you know, we were successful at it. We couldn't get it to scale where we wanted to.

But I think it did two things… two objectives we had. To elevate housing to the level of a Human Right. I think up to that… until we started using that language, it was just a slogan for some people. And I think now people are thinking outside of the box. And then the other thing is to change the fundamental relationship to land and to start to talk about CLT's back in 2010, 2011... [There was] a little bit of talk about it, but it wasn't much. Right. But, you know, we tried to push it to the forefront. We saw it as the model.

Gabriela: Was this led by Picture The Homeless?

Rob: No. So it was led by Take Back the Land. So, very interesting. I think. And I share this… I think that's where I sort of parted ways at that point with Picture the Homeless, because there were differences, I think. And it shows me some of the challenges of social justice groups liking attention. So I think Take Back the Land was receiving a lot of attention.

Picture the Homeless wasn't. We did a lot of work without funding. And, you know, I think there was a thought that we were getting a lot of money to do the work we do. First time I ever went to Rochester, Max says: “One of us has to go. So how much is a bus ticket? Bus ticket is $130 dollars from New York City. Well, Rob, you're closest. I'm in Washington, DC”. I reach in my pocket. I have $60. Max says: “I'll send you another 80. You can go get a bus ticket.”

And, you know, we just pooled our money that way. So, you know, this was a Take Back the Land effort. After I went there with Picture the Homeless, we got a lot of publicity. We started traveling up and down the east coast. We also tried to work with a group called City like Vida Urbana up in Boston, who was… They weren't doing exactly similar type work, but they were fighting against foreclosures and evictions in a way that was a little bit different than other people.

So we started to think, Max and I said: “Okay, from Miami to Boston, we could have this presence along the east coast”, but we couldn't get people to buy into the idea, so we backed away from that. We reached out to a friend, Kali Akuno, from the Malcolm X grassroots movement. He invited us to his house on Labor Day weekend 2009, and we came up with this idea of Take Back the Land going national through these local action groups.

So people had to believe in ideology, our way of thinking, you know, seeing housing as a human right, believe in the community land trust model, decommodification of land and housing. And we came away with an agreement that weekend. And then we said: “We're going to roll this out on May 1, 2010, in association with the real Labor Day around the world”. We did 45 actions in 25 cities. Got incredible publicity.

One man in Toledo, Ohio, Keith Sadler sealed himself in a home, and it took the FBI like two days to get them out. And they were freaking out like, who the hell is Take back the Land? Where did you get this stuff?

Gabriela: So it became like an umbrella organization for all these very local groups, right?

Rob: Right. Local action groups that believed in our ideology. So Max and I knew we could draw the press in and we would get them the publicity for doing the work that day. Interesting thing here, how this work at one point went mainstream.

So there was a point where we combined with the group Occupy, right? Occupy came to Take Back the Land and said, we don't want to reinvent the wheel. You guys have been doing this work, right? So let's get together and form something. So we called it “Occupy our Homes.” And in early December, we had planned a day of actions, December 6, 2011,

which had happened here in New York, 702 Vermont Avenue in Brooklyn. But we did… I was traveling. Max was in Miami at the time, and J.R. Fleming was in Chicago. We were each approached by Investors Daily to be interviewed. We won the front page… these radical black folks.

I was on my way to a conference out in LA with NESRI [National Economic and Social Rights Initiative] at the time, a US Human Rights funds conference. And I was at LaGuardia airport, and I got this phone call, and it's Investors Daily: “We want to interview you about your, you know, the challenges. You guys are throwing it to big banks and what not”. You know, three days in a row, we were all interviewed by Investors Daily. And we're like: “Holy cow, this is huge”. You know, so the only issue there was, we couldn't get it to scale. But it really set forth this thinking about Community Land Trusts, decommodification of land and housing.

And I think, you know early on, we would get angry when people started using our language. And it was Cathy from NESRI who said to me: “Why do you care? As long as the movement picks up from it? You want to make social change. You know, people are starting to grab onto it, roll with the flow.” And that's something I had to learn over a period of time. But, you know, I've accepted it now, and I'm grateful that this movement has, you know, blossomed.

Gabriela: Yeah. So you're talking about… 2000…

Rob: This is 2011, 2012. Yeah. Right around Occupy [Wall Street].

Gabriela: And around that time, different groups were already, like, envisioning…

Rob: Right, starting to talk about it, starting to think outside of the box, as I like to say. [Like], how do we relate? So we became this group that was idolized.

We were militant. We were black. We had very little resources, but we were setting forth some radical social change ideas.You know, people were calling us activist academics, intellectuals. Activist intellectuals. Because we were locked down with Peter [Marcuse], Neil [Smith], Tom Angotti. I mean, David Harvey supported us and we were writing articles about the work that we were doing. So we had all these different academics supporting our work and saying: “Okay, these guys are thinking differently, and this is what needs to happen”. So I think the movement caught on to that and said: “Okay, they're doing something different. What is it they're doing? And let's start to drill down on this”. And then I think, you know, community land, trusts, became the rage.

It became the model that people started talking about and, you know, realizing that we have to move in this direction. So we had one here in New York. We had Cooper Square [that] everybody knew about. But I don't think it was at the forefront the way it could have been.

So there were those. There was a circle of people who knew about it, who were very much involved. But, you know, we knew Tom Angotti and some other folks were involved, so we would have to push Tom to tell us more about it.

I didn't know Francis well. I knew of her, but I didn't know her well. So, you know, it wasn't like I could just sit down with Francis [and tell them:] “tell me what you went through”. But, you know, I started to do my homework and read and then ask questions, and particularly [to] Tom, because I had a long relationship with Tom going back to my days at Take Back the Land and Picture the Homeless.

And,early on, some of those same academics formed a Right to the City reading group. Where they would give us readings to read and then come and talk about what a right to the city would look like. And a lot of it early on was based on Henry Lefebvre's theory of the right to the city.

So not many organizational members would show up. So I found myself one day sitting at the [CUNY] Grad Center [with] Peter Marcuse, David Harvey, Tom Angotti, Neil Smith. And Peter just goes: “What do you want to talk about, Rob? The show is yours”. And at that time, the Right to the City Alliance, which was a group of New York groups, were trying to put together a platform.

And, you know, we started to dissect that platform a little bit, but it gave me access to some activists, some academics that I probably would have gained access to anyway. But to be able to build a relationship with them and learn from them and be mentored by them was pretty cool.

Gabriela: Yeah, I remember some of the study sessions at the Brecht Forum with Peter and Tom.

Rob: Yeah. So, you know, some of the community based organization members were intimidated by it. You know [like]: “Picture the Homeless” man. They were like: “I'm not going in there.”

Why not? I always felt like: “You know, okay, I'll take the table. I'll sit there. I'm gonna learn, and I just absorbed what I can”. And they were always willing to share, and they always opened their doors.

And you know, the cool thing for me as I started to learn about this stuff is they always would provide me with readings and [they’d] say: “Read this, and then come back and let's talk about it”. I wasn't a big reader at the time, you know, but after I started working with Picture the Homeless, [then] we started doing takeovers and then Take Back the Land… All of a sudden, I saw people flocking towards me and saying: “Okay, here's a little bit about history” right. And it allowed me, as I mentioned earlier, to put a thread through some of the historical things I lived through, some of the historical things I was taught. And then what is happening now, and to see that a lot of it continues.

Gabriela: And were you part of… I remember also around that time that there were some groups that started getting together and talking about this kind of coalition of community land trusts.

Rob: Right. So, you know, there was a lot of conversation. Picture the Homeless was involved.

I hesitated a lot because what I saw over a period of time were the different housing groups fractured, and I saw myself as this voice that people listened to that is respected. So I wanted to be careful about what I said publicly. You know, I would say some things behind closed doors. I'd be observant. I kept somewhat of a distance, but at the same time: “what can I help you guys understand? You know, I want to share with you some of our thoughts from Take Back the Land”.

And I would do teachings sometimes with some of these groups, but I found a lot of tension within these groups and it sort of turned me off. And this is one of the reasons why I leaned so much outside of the country. You know, I saw these, I want to say, fractures, fissures, whatever you want to call them, amongst the groups.

And for me it was interesting because I was always connected to PhD students from outside of the US who would come here to study on fellowships. And many times they would tell me: “Well, I was told to reach out to you by, you know, so and so would Rosa Luxembourg foundation or so and so”. And one was a gentleman by the name of David Skeller came to a space we had like the old Brecht Forum. It was 16 Beaver [Street], George Caffentzis, and Silvia Federici, like, gave it to the movement.

And David [Skeller] called all the housing groups to a meeting one night, and he just chewed into us and said: “You know, I’ve worked with all of you the last couple of summers, but none of you work with one another. Right?” And I'm like, in the back cheering and people are looking at me. But he was right. He was right. And I think some of that still goes on. And I think a big part of that is foundation dollars and philanthropic money dictates the work, which should be different. We should be able to dictate to philanthropic organizations what our needs are, and if [they] want to support this work.

Gabriela: And Rob, tell me about your role right now with Cooper Square.

Rob: So I was recruited by two long time board members of Cooper Square community Land Trust, Monxo Lopez and Tom Angotti. Tom is somebody who I go way backward to my days at Picture the Homeless,

but they thought I would be ideal for the board of the Mutual housing Association and the CLT. And so I joined right away. Those are two individuals I respect a lot. And if they look at you that way, then I'm sure there's some role for me to play within this group. And I was happy to be recruited by it. I do think now that I'm there, you know, you don't want to come in with your guns blazing, but I wanted somehow to bring in popular and political education, because I'm not so sure all the residents understand what they have. And I think, you know, if you take a step back and you say: “Okay, if I wasn't living here, what would be going on? Right? So how do we do that? That's the challenge” right?

And you know, there's always going to be people who are different, have differences. Even some of the people who are experiencing this special way of living, think of how they can profit from it. And… it's not [about that]. This is about communal living. This is a different way of life. So how do we get that across to people?

I think you have to have programs in place that will do the education. So for me, that's a role I would like to play down the road. You know, I teach a course here at the new school, and last week we got into a discussion about public housing, and there is an academic out on the West Coast by the name of Gilda Haas. I don't know if you know her.

She does a popular and political education website called Doctor Pop, and it just takes complicated manners and issues and simplifies it through little cartoons and other things. It's fantastic. So she did a comic book for my human rights organization, NESRI [about] the value of public housing. [There’s] two families, one lives in rental housing,

the other lives in public housing, and they're having a discussion in the park. So I just think, you know, I would love to bring in popular and political education into the space. I think there are opportunities there that people don't recognize. Right? And when I say people, I think many of them residents. And even some of our fellow board members, you know, I'd love to see them understand the value of what Cooper Square is. Right. So if that's. That's, you know, that's down the road. I've enjoyed my stay there. There's been some challenges. Personality issues. Personality clashes. Right?

But that's going to exist in any coalition or alliance. And, you know, hopefully, we can put it on the table, chop it up, and come to consensus. I'm always in favor of that. I don't think we have to run around, you know, hating on one another or pulling in a different direction from the others.

We should all be pulling in the same direction, but that takes communication. And sometimes it can be challenging, but I'm always up for a challenge. I love challenges. It's the athlete in me. I've faced challenges all my life, and I'm like: “Okay, bring it on. [laughs] Let's do this”.

Gabriela: Are there any other organizations or small coalitions, you know at the neighborhood [level] that are trying to create new Community Land Trusts, and do you think that they know what they are wishing for? In terms of the complexity and responsibility, talking about land?

Rob: I don't. I'm not so sure they do, and I don't want to throw anybody under the bus. But I say this about a lot of… especially board members. I will say this is something I've learned in my time doing this work. People are very proud to wear a badge that says: “I'm a board member of”... but to put their hands in the dirt and do some work,

not so much, you know. So I don't think the groups realize the heavy lift that this can be. I'm hoping that they open their minds and they're willing to learn. Right. And really, and really dig down deep and say: “Can we do this? Do we want to do this?” I think that's a big question. can we make this commitment? It takes a commitment, right? So, you know, it leaves me thinking a lot. I've experienced infighting, I experienced challenges. I'm not involved in those groups. I was just away with some members of Picture the Homeless. And I got two different views on El Barrio, you know, [in] East Harlem Community Land Trust. So, you know, there are differences there. And I think that has to do with personalities.

And sometimes people just can't get past the personality stuff. You have to check your ego at the door if you want to do this good work. Not easy, I get it. But for the sake of community and the sake of social change, you know, you have to be willing.

Gabriela: Yeah, and kind of like looking at the different models… You know, you have been traveling a lot and seeing how people relate to land and to housing in different ways. And here in the US, private property is sacred, no? And all these groups are fighting for land or properties to be managed in collectivity, to have shared ownership. How do you see that shift? Because I see a big shift that has happened in the last ten years. More and more people are thinking about [how] there could be other alternatives.

Rob: So there has been a shift. I think the shift could have been stronger than it was, because I'm not so sure how open people are here in the US to internationalism, right? So I mentioned Brazil's constitution earlier. It says land has to serve a social purpose. One of the biggest movements in Brazil is a movement for agrarian reform, re-appropriating land because of that constitution. It took different factions of the community coming together. Legal... So for the policy, the people living in communities… but they're starting to re appropriate land in ways that we never thought possible.

So it's going to take us probably a lot more, but we should learn from these movements. It's fundamental that our Constitution [changes]. Our constitution is where the floors start, right? And as long as we stand by that Constitution,

the way it's currently constructed, we're pushing a rock up a hill, right? I often lecture Law Schools and say the Constitution needs to be amended in so many ways and it's flawed, right. From the very first sentence when it says: “We the people”. And I would ask the question: “Who are those people?” Because at the time, people who looked like me were considered three fifths of a man. So it was a select group of people, a good old boys club, who decided that property rights are the thing. [They said:] “This is my land, I'm going to control it."

I do think if the social justice groups here in the US would open their minds and sort of get out of and look internationally, there's a lot to be learned. I've learned so much from traveling internationally and being exposed to international social movements and how people go about things differently. You know, whether it be land reform movement

or even domestic workers from the Philippines, right? Not relying on philanthropy to do their work. They do the work because we need change in our country. “So I go to my regular job. When I'm done, I go do this other thing, right?” And, you know, it's hard to conceive that happening here at such a scale because the first thing people say is: “I need a Metrocard, I need a meal”. And when you start to see people in other countries… I'm always reminded of going to Medellin, Colombia, and watching an assembly that was called on a moment's notice. Like 500 people show up, about 50 of them are barefoot, like no shoes on. But it was important to be there and they showed up. So I think there's so much to learn, but we have this exceptionalist attitude. Like: “we do everything better”.

And no, I say: “Let's take a look at some of these international social movements, right? I think they do a pretty good job and they make some change, right?”

Gabriela: Yeah, you're right, Rob. And thinking about the new generations of all these movements, but also the few Community Land Trusts that are running and that have managed to have property… How do you see the future of those communities in relationship with the engagement of residents, and you know, there is a lot of work to do. So you [were] talking a little bit about that, what is needed?

Rob: I think, again, institutionalized, popular and political education. You have to understand why we're doing this, what this is about, why this is a better way of living.

And unless that's reinforced, it slips away. It dies with certain generations. So it's something that has to be reinforced. I do think we're at a time now where young folks who are getting educated are not buying into to this thing called the American Dream and are figuring out different ways of life because [they think:] “Everything that was told to me doesn't seem to be working. So I got to figure something else out. So maybe this new relationship to land and housing, maybe that's the way to go. Because I can't afford $5,000 a month rent. I can't. I don't want to go out and find six roommates to live with me so I could afford to rent.”

So I do think as I talk to young students, I always say it may not change to the world that I want to see while I'm still here, but me and others have left a set of tools for you to continue the job, to move this forward.

And I do think there's some thinking outside of the box, and I think it's across different disciplines. Right? It's the Law School, students are thinking differently. You know, when somebody as radical as me gets invited to Duke Law School to lecture… [laughs] Okay, something's changing. Like: “Whoa, Duke, this prestigious law school?”. But the students continually reach out. They want to see something different. They want to see a different world, but they want guidance. They really want guidance. And you know, maybe the guidance isn't here. Maybe the guidance is in other countries.

But that's why I do my best, if there's opportunities to bring organizers from other countries here. I've always appreciated the folks at the [CUNY] Graduate Center, [the] “Center for Place Culture, and Politics”, because, you know, they'll always open up a little budget line and say: “Okay, Rob, you know, an organizer in this country, who should we invite?”

You know, and it gives them an opportunity to come home and come here and talk about their way of doing work in their particular country. And I think the more we share those opportunities, the better off we are all going to be because of it.

Gabriela: Thank you so much, Rob. This has been super inspiring. I don't know if you would like to say anything to the new generations of organizers?

Rob: I just think we have to open our minds. Some of us have lived in a period of time where we knew that the system wasn't working for us, it was working against us. So it's up to us to come up with fresh, new ideas and implement those ideas. A lot of times, we fight for policy, fight for change, and it gets written, but it's never implemented.

So remember to implement and remember the economic pieces of it. Sometimes it takes a certain budget and we never think about the money piece. So, you know, we can redirect budgets also, but we have to be willing to do that.

Numbers can be scary, but there are plenty of progressive economists out there that we can partner with. We don't have to do it all, right? So I think collaboration and working together is the way we're going to achieve the world we want to see. Real social change.

Gabriela: Thank you so much.

Rob: Thank you. I enjoyed it.

Gabriela: Thank you. So inspiring.

Rob: Thank you. Thank you, Gabriela.

Roberson, Robert, Oral history interview conducted by Gabriela Rendón, October 5th, 2022, Cooper Square Oral History Project; Housing Justice Oral History Project.