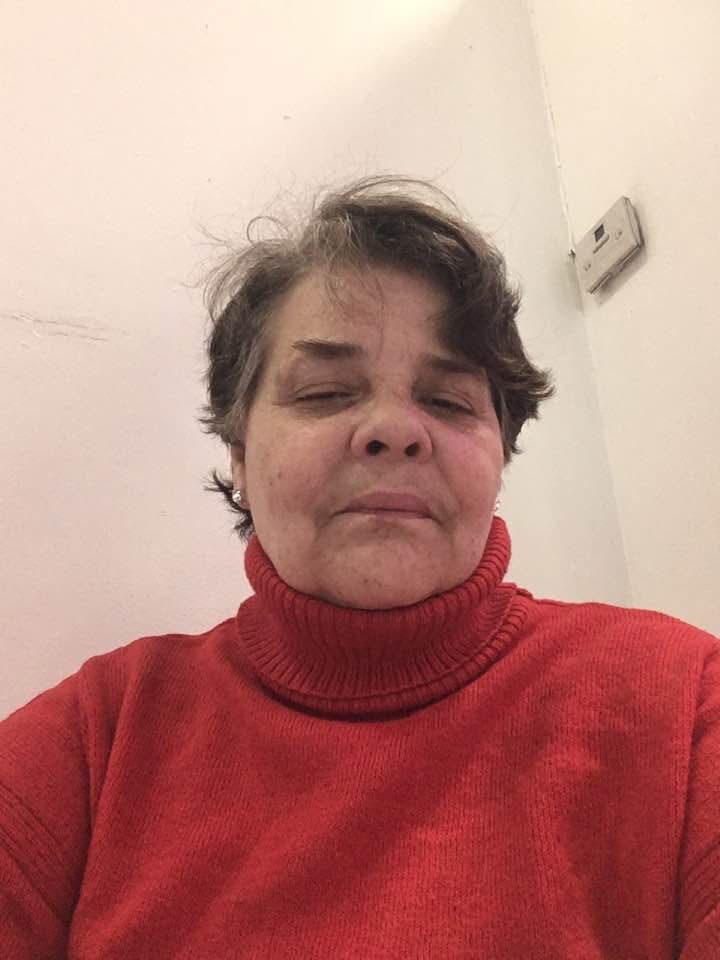

Kim Statuto

Kim Statuto has a keen eye for identifying discrimination and injustice, as well as an energetic approach to fighting for the dignity of low-income people. “It was in me, from a child, to stand up and protect, to take care of your community, and to help others.” In this interview, Statuto narrates her life trajectory across three New York City boroughs, highlighting her firs-hand experiences with housing discrimination, landlord harassment and neglect, and a fraudulent eviction as a single mother of four children. A CASA leader from 2018 until 2023, she shares some of the insights she has gained while mobilizing for tenants’ rights, including her criticism of rampant income inequality and the abuses committed by corporate landlords.

Statuto can trace an awareness of the importance of community organizing to her time growing up in Brooklyn in the 1960s and 1970s. She was raised by a Black foster family in a predominantly Black neighborhood while being white, and she remembers seeing residents get together in block associations to support each other and keep the neighborhood safe. These associations gave her a first “understanding of involvement and caring and voicing concerns outside the home.” At about nineteen years old, Statuto moved to Manhattan and reconnected with her birth mother. After having her first child at twenty-three, Statuto and her mother moved into an apartment in Hell’s Kitchen. Alongside neighbors, they soon formed a tenant association to look after each other, organize social events, and voice any potential concerns.

After her mother’s passing, Statuto and her by then four children stayed in the same apartment. They were entitled to pay a low rent inherited from her late mother, but the landlord began deploying a series of tactics to try to evict them. “That was the first time I understood what being discriminated against meant. I was discriminated against because I was poor.” In 1994, the landlord succeeded in evicting them after filing a fraudulent case claiming nine months of non-payment while not cashing the checks disbursed by Social Services on Statuto’s behalf. She recounts the traumatic experience of watching the marshals put her family’s belongings on the street and the high stress of having to find an emergency solution to house and take care of her children. As she put it, “I am also a product of that eviction. Wrongful as it was.”

Statuto describes the hardship and “culture shock” of going through the shelter system with her young children. While searching for an apartment, Statuto again experienced discrimination, as most landlords did not want to accept a single mother with four children on social assistance. They finally managed to move into an apartment in the Bronx in 1995. Around this time, Statuto became involved in an initiative called Community Voices Heard (CVH), which organized against then President Bill Clinton’s “welfare reform.” In the interview, Statuto dissects her criticisms of this platform, its anti-poor rationale, dehumanizing practices, and the failures of its programs. As one of the founding members of CVH, Statuto shows appreciation for the work they have done advocating for those on welfare. “That was my first community organizing or getting a bug of standing up for what I believe in.”

Statuto’s next experience with community organizing was triggered by landlord neglect, which ultimately brought her to get involved with CASA. Her and her children’s initial years living in the Bronx had been marked by stability, until the building switched hands to new landlords. Her struggles reached a turning point in 2017, when the gas was cut off for months while the landlord refused to respond to tenants’ complaints. Statuto used to pass in front of CASA and suggested to her neighbors that they should reach out for support. “They [CASA organizers] came. They told us about our rights. They heard our cries.” With CASA’s guidance, Statuto and neighbors formed a tenant association and successfully sued the landlord, winning two abatements and leading him to lose the property.

In reflecting on her time working with CASA, Statuto highlights the importance of fighting for right to council. She considers that, had this right been in place in the 1990s, she and her children would’ve been spared the life-altering experience of an eviction. Statuto criticizes the lack of attorneys to guarantee low-income tenants’ right to counsel since the end of the covid-19 pandemic. She describes the unfairness and power imbalances of housing court if a tenant is unrepresented.

In discussing the yearly campaigns with the Rent Guidelines Board, Statuto denounces the narrative that most landlords are “mom-and-pop landlords” struggling with high taxes and utility bills. She argues that most rent-stabilized buildings in New York City are owned by corporate landlords whose high profits are not disclosed. Reflecting on the period of the pandemic, she is particularly critical of the limited support granted to the unemployed and people on welfare. She believes that had the authorities listened to their demand to cancel rent, tenants would’ve been duly protected and a post-pandemic eviction and housing crisis would’ve been averted. “When we were fighting for Cancel Rent, you should’ve canceled it (…) Now you’ve got tenants being dragged into court, being asked to give money that they don’t have.”

Statuto stepped down from her leadership role with CASA in March of 2023 to become a member of Community Board 6 in the Bronx. She learned about community boards through CASA and sees them as a key institution shaping the future of communities. Despite no longer being ahead of CASA, her concern for housing justice remains. Looking at the future, she asserts, “Fighting for Right to Counsel statewide is what is needed. Landlords need to know that they can no longer take advantage of tenants. Tenants have rights.”

Class discrimination

Community boards

Community organizing

Covid-19 pandemic

Dehumanization

Eviction

Gentrification

Housing court

Landlord neglect and harassment

Rent-stabilized apartments

Right to Counsel

Shelter system

Single motherhood

Tenant associations

Welfare reform

Bill Clinton

George Pataki

Mario Cuomo

Abdul Khan

Eric Adams

Community Board 6

CVH (Community Voices Heard)

DHCR (New York State Division of Housing and Community Renewal)

EAU (Emergency Assistance Unit)

ERAP (New York State Emergency Rental Assistance Program)

MCI (Major Capital Improvement)

RGB (Rent Guidelines Board)

Section 8 housing

WEP (Work Experience Program)

Brooklyn

Manhattan

Hell’s Kitchen

The Bronx

Nelson Avenue Family Residence, the Bronx

Campaign for Right to Counsel in New York State

Campaign for Right to Counsel in NYC

Cancel Rent

Eviction-Free Bronx

No More Major Capital Improvements

Rent Guidelines Board campaigns

| time | description |

|---|

00:00:41 | Statuto describes growing up in Brooklyn in the 1960s and 1970s and being raised by an African American foster family in a predominantly Black neighborhood while being white. Statuto recalls learning early in life about the importance of community organizing through the work of local block associations.

00:05:48 | Recounts her move to Manhattan at nineteen years old and reconnecting with her birth mother. Relates having her first child at twenty-three and moving in with her mother to a new building in Hell’s Kitchen. Explains how they and neighbors immediately created a tenants’ association.

00:14:02 | Statuto relates how, after her mother’s passing, she stayed in the apartment with her then four children. Reports the harassment tactics the landlord used to try to evict them because they were entitled to a very low rent paid by Social Services. In 1994, the landlord eventually submitted an eviction filing by claiming nine months of non-payment while not cashing the checks disbursed by Social Services.

00:17:44 | Explains how she and her four children were evicted and placed in two consecutive assistance units before being relocated to a shelter. Narrates the humiliations of being evicted by marshalls. Relates the hardship of staying in an assistance unit with her children amid uncertainty and unsanitary conditions.

00:31:01 | Statuto describes how they were transferred to a family shelter in the Bronx at the end of 1994, where they found better conditions and more stability. Shortly after, her family qualified for emergency access to Section 8, allowing them to relocate to an apartment in the Bronx.

00:34:17 | Statuto reports how her previous landlords’ nine months’ worth of uncashed checks were sent to her while she was still staying in a shelter. Stresses how then she learned about his tactics to discriminate against and evict her family so he could raise the rent to future, wealthier tenants.

00:38:00 | Describes how she became one of the founding members of Community Voices Heard, an initiative organizing against then President Bill Clinton’s “welfare reform.” Details her criticism of the Work Experience Program.

00:49:37 | Statuto recounts how, in her search for a rental apartment, she became aware of landlords discriminated against her for being a single mother to four children. Relates how in 1995 they managed to move into an apartment after seven months in the shelter system.

00:57:09 | Describes how the situation in her building deteriorated rapidly after it was sold to new landlords who were eventually arrested for fraudulent practices, and the building went into foreclosure. Reports that in 2009 the building was bought by Abdul Khan, who harassed tenants and neglected repairs and basic services such as heat and hot water.

01:02:44 | Chronicles how in 2017 the gas was cut off in her building and the landlord did not respond to their complaints. Recounts how she and neighbors then reached out to CASA for support. Describes CASA’s work educating them about their rights and advising them to form a tenant association (TA). Reports how their TA took the landlord to court, won two abatements against him, and he ultimately lost the building.

01:10:42 | Explains her involvement with CASA and highlights how she’s particularly proud of the work CASA has done for right to counsel and in the campaigns with the Rent Guidelines Board (RGB). Also stresses the importance of CASA’s campaign against Major Capital Improvements (MCI).

01:16:57 | Describes problems with current landlord neglecting repairs and how she’s also involved in organizing in her son’s building, because the landlord is unwilling to recognize his succession rights or the abatements tenants had previously won.

01:23:19 | Criticizes limited assistance grated during the pandemic to those unemployed and on social security. Highlights the importance of having right to counsel pass statewide. Argues that rents should’ve been canceled during the pandemic.

01:34:16 | Statuto denounces unfairness and power imbalances in housing court harming unrepresented tenants (especially those who are monolingual Spanish speakers). Denounces shortage of attorneys to guarantee low-income tenants’ right to counsel.

01:41:58 | Discusses how no rent increases should be approved by the RGB given landlords’ undisclosed profits and the widespread lack of maintenance and repairs in rent-stabilized buildings. Criticizes the narrative around struggling “mom-and-pop landlords” and stresses that most rent-stabilized buildings are owned by corporations.

Zacca Thomaz: Today is May 26, 2023. This is Diana Zacca Thomaz, from the University of Amsterdam. I’m here interviewing Kim Statuto on Zoom. This interview is for the Parsons Housing Justice Lab’s Oral History Project. Kim, let’s start by talking a little bit about your personal background. Tell me about where you were born and raised, and what was it like to grow up there.

Statuto: Good morning. Glad to be with you. My name is Kim Statuto. I was born in Brooklyn. I was raised in Brooklyn. I’m actually a product of foster care. I grew up in an area that I really couldn’t identify with, because I was with people that were not of my nationality. I grew up in an African American household in the 1960s. I’m a ‘60s baby. Although it was a very decent neighborhood–it was a tree-lined block with private homes, homeowners–none of them looked like me. I grew up confused as to “How did I get in this place with these people who don’t look like me?” Customs and beliefs were different. I didn’t know anything else, so I just thought that that was normal. But as I became a school age child, it didn’t look right to me.

One thing I did see early on, growing up in Brooklyn, back in the 1960s, where blocks had block associations, we now call them tenant associations and buildings. But I grew up on, like I said, a private home block, and there were block associations. And the people that I grew up with were part of the block association. And I saw them commit and participate in keeping the block safe. Giving events throughout the year to help families, to keep the block upkeep, decent. I saw that organizing bit very early on in life. But this was an African American community. That’s all that lived on that block. So, I kind of felt like a sore thumb in the middle of it. Yes, they did have us involved in events and actions that they took part in. And I did get an understanding of involvement and caring and voicing concerns outside the home that may not have been what was going on in the home, but that’s what they projected to the general public.

I remember [it] being called New Jersey Block Association very well. I remember my first job as a youth came through the Block Association. That was the connection that I did see. Families and communities helping one another. Children didn’t get hurt then. If your parents weren’t home, other parents looked out for you. So, I saw that early on in life and it did give me a sense of “you have to speak up when you see things aren’t right.” Just because that’s what I saw them do. I remember, growing up probably, 1973,74, which is when I was thirteen or fourteen, I remember a gang trying to invade the community, and how they stood together and blocked off the block, they weren’t going to let it come to their neighborhood. The gang was actually called Tomahawks. I remember that very well. And just how those people stood up and fought to keep their block straight. After I left there when I was eighteen, I didn’t see that so much going through life. But it was in me, from a child, to stand up and protect, and to take care of your community, and help others. Go sweep up their lawn or help them with the snow if they were elderly, you know, things like that. Those are the things that were instilled in me growing up.

Once I became an adult and moved on, I didn’t see that so much, kind of faded away from that. When I had my own apartment in Manhattan on 45th Street—I had to have been about nineteen or twenty [when] I think I first heard about the RGB, Rent Guideline Board. I remember somebody was handing out flyers or something. And me, I guess it must’ve been that initial bug of “What is this about?” And I remember going to a hearing in Manhattan about it. I’m not going to say that I understood everything about it, but I remember going to a hearing about it in Manhattan at a very early age. I lived in Manhattan in the Hell’s Kitchen area. Forty-fifth Street and 9th Avenue. And then I moved to 47th Street between 10th and 11th, which was called Hell’s Kitchen area. You know, you work, you go through life. I wasn’t a mother, I was single, but there were little things that came across me and I went and I got involved in. Briefly, not a whole lot, not a whole lot, not until after I had my first child. When I started seeing injustices regarding housing, police, community, things like that. Which kind of brought me back in a little bit, just a little bit, not much. I think when I was nineteen or twenty, I reconnected with my birth mom. That was an interesting experience. She has now passed on and has been passed on for a while. So those part of my years were just getting to know her.

I had my first child at twenty-three. Just going through life and trying to adjust to what a community looked like. At this point, I lived on 47th Street in a new building, that was not like it is today. New buildings were coming up, but they weren’t coming up as quick as they’re coming up now. My mom and I had got accepted into this building. It was a two-bedroom building. And right away, once all the tenants were in the building, we started a tenant association. So, it goes back to that far, twenty-three, twenty-four years old. We looked out for our tenants in the building. We looked out for the children in the building. We formed the tenant association, and it wasn’t because anything was wrong, this was a brand new building. Just because we wanted to be connected. We wanted to let owners or managers know that we’re not going to be rolled over on, this is a new building, you’re going to take care of it. At the same time, you’re going to hear our concerns if any should arise.

We held events for the children, holiday parties for the children. So again, it comes back to growing up in that. It was easy to fit into that tenant association. We met monthly. If there were any concerns or if a neighbor or a tenant was having a problem, we tried to come together and help that tenant out. So that was another experience. Not that I was out there fighting or anything, because I wasn’t really living in an unsafe condition. We had neighbors that cared. It was a very diverse community. The community was made up of all kind of people. We were smack-dab in the middle of Hell’s Kitchen. What do they call them, railroad flats, across the street from us. Railroad flats were apartments that ran straight through, there were no dividers. It was just straight through.

They were trying to build this community up to a different makeup. But you got to remember, there are people that lived there forty, fifty years, who were opposed to new buildings coming in and the change of their neighborhood, the displacement of businesses that were there. But at that time, we weren’t looking at it like that. We were looking at it as “It’s making the community better.” We didn’t understand that people were being displaced. We weren’t understanding that, that developers and landlords were getting [tax] breaks to do this, but they weren’t thinking about the people that were living in this community and who they were going to put out.

Like I said, it was a new building. We didn’t know before this new building was built that it was four buildings and that all of those tenants that were in those four buildings were displaced to build this building, that we didn’t know that at the time. Until months later, [learning] that people were displaced, after being in the neighborhood and talking to people and they’re telling us, “Oh, well you didn’t know that there was four buildings there?” And “Y’all are lucky y’all got in there, because the people that were living there were either paid or bought out, maybe lied to and promised that, once the building was built, that they would have first opportunity of coming back in.” And that didn’t happen.

So how appalled we must have felt. Wow. We didn’t know people lost their apartments. We didn’t know that people that had been living in this neighborhood twenty, twenty-five years, were now who-knows-where for whatever reason. We don’t know the tactics that the old landlord may have used to get them out, to sell the land or the plot to the developers. We didn’t know none of that until later on. I’m talking about maybe four or five years down the line, okay? Here we just thought we got a new building, we got new apartments. But we weren’t understanding of what happened to the people that were displaced out of there. And if they were given a fair amount of money to move. Did they go through any hardships? Did the landlord—We didn’t know nothing. Much later on in life I learned how they can do that: they turn off services. They offer certain groups of people certain amounts of money to move. And some that didn't want to move probably got displaced, because if they got most of the people out, then they could come in and take over the building. We didn’t know that, and that’s kind of disheartening, later on down the road, when we started learning the history of this particular building. It is still standing today. I’m more than sure it is thriving. As I said, I lived there with my mother.

My mother passed away there, not there, but that was her residence. And of course, because she passed away and I was on her lease, they had to give me her apartment. They weren’t too kind to that. My mother was paying a very low rent, and they couldn’t increase the rent just because she passed away. It had to stay at the level that it was because I was her child, and I was living there, and I was on her lease. The landlord didn’t like that very much, and for years he fought tooth and nail to get me out of that building. It was a two-bedroom apartment. They tried tactics of taking me to court for nonsense. Nonsense. I was a little bit down on my luck at the time. I had three children, actually four. I was on Social Services. Social Services was paying the rent.

He took me to court for not letting the exterminator in or things like that. Stupid things. I didn’t realize at the time that it was a form of harassment. I also didn’t understand at the time that he was trying to gain his two-bedroom apartment, that my mother was only paying $222 dollars a month’s rent. In the heart of Midtown, Hell’s Kitchen, 47th Street, between 10th and 11th. Prime real estate. Walking distance from Restaurant Row, Theater District, 34th Street. All of those elements played, but I didn’t realize none of that at the time. All I knew is that he just kept bothering me. Eventually, he couldn’t get me out on the stupid things he took me to court for. Again, I tell you, Social Services was paying the rent. He held nine months of checks that he did not cash and took me to court for nonpayment of rent. Social Services intervened and said, “How can that be? We’ve been paying her rent. Here’s the printout.” I’m not familiar with housing court, I’m not familiar with housing laws, or anything like that. But Social Services did show up. Social Services made a plea to give us three days. This was 1994. Back then, it took them a couple of days before they could cut you an emergency check. It’s not like it is today that they can do it in one day if it's an emergency. Back in the 1990s, it took at least three days. Because the case worker had to write it up, the supervisor had to send it off, and they had to send it to another unit to get the check. Social Services was willing to pay this back rent even though they knew they sent checks. But there’s a tracking mechanism, and it showed that none of those checks were cashed. I’m not familiar with housing court. Housing court rejected it.

All I know is the next thing I hear: “Let the eviction stand.” I have four children. I just had a newborn child; she was three months old. I have three older children. “Let the eviction stand.” My thinking, I thought they had to serve me another eviction notice, and that this would give Social Services time to cut this check that they were talking about, this rent that wasn’t paid. Well, it didn’t mean that. It meant the next day the marshals came and evicted me. October 12th, 1994. So, I am also a product of that eviction. Wrongful as it was. Because later, a couple of days later, sitting in EAU at the time—that’s what it was called, Emergency Assistance Unit—because we were homeless. They did their due diligence in trying to find out how that I get evicted from an apartment that Social Services was paying for, and that Social Services had proved that they were sending checks. The only thing was these checks weren’t being cashed. So, they don’t know what happened to the money, but they knew they were sending it. They EAU at the time—and you have to understand this: I was a woman with four children. I didn’t fit into this homeless population. So, the EAU was really trying to figure out: “What happened here? Because her rent was being paid; there was nothing else wrong. What’s going on here?? Well, later on, we found out they wanted the apartment, because they could get much more rent for the apartment than what was being paid.

Digging [laughs], digging through the layers of stuff that management or landlord had did, they had offered the landlord, “Listen, we’ll send you a check right now to pay her back rent, to get her back in the apartment.” They was like, “Yeah, okay.” I had to intervene because what I saw prior to me being evicted, they had evicted a tenant underneath me. She had lost her son, through violence, and things kind of fell off because she was grieving. She was devastated. She lost her son when he was seventeen years old, and they evicted her. And she tried to get her apartment back. And what the landlord did, was say, “Okay, you give us the money.” They gave them the money, not for me yet, for this tenant. And then they told the people that put up the money, “Oh, she’ll go on the waiting list. When another apartment becomes available, we’ll give it to her because we’ve already rented out her apartment.” So we were like, “What?” I told EAU that don’t pay that money because I’m going to tell you what they’re going to do. They’re going to take your money and they’re going to tell you, “We’ll put her on the waiting list.” Well, basically what they told him is that, “Oh, we already rented her apartment.” Mind you, I’d only been out six days. How did you rent this apartment? You understand what I’m saying? That was an eye-opener for me. Still not digging into what really went wrong but knowing something went wrong here and just trying to secure a place for me and my children. We were put into a system that was a culture shock. Culture. We had to sleep on the floor for four days. I had a newborn baby; she was three months old. The kids couldn’t go to school because if you left this unit, thet Emergency Assistance Unit, and they called your name, you lost your spot.

Zacca Thomaz: Was this a shelter, where you were staying?

Statuto: Yes. Well, this is the first place you go before you get to a shelter. It was called the Emergency Assistance Unit. It is still in place here in the Bronx on 151st Street, down nearby where Target and all of that is. It’s still there. There were crowds of people, people laying all over the place. They were giving us meals that were boxed or, you know, sealed plates or whatever it was. My children got sick, they were throwing up. We had no clothes. Remember, we were evicted. The marshals—Actually how I found that I was being evicted. I went to pick up my children from school, three of them. Coming down the block, my oldest child saw our belongings on a sidewalk, and he started asking me, “Mommy, why is our couch out on the sidewalk?” So, when I look, I’m like, “What's going on here?” When I came down the block and I got up to the apartment, the marshals was there, and I was like, “What's going on?” And of course, they hand me the eviction papers. They told me, “You have five minutes to go in and get whatever you can get. You are not to damage anything in this apartment. If we see that you’re trying to damage anything, we will arrest you. But you got five minutes to go in and get what you need.” Okay? And in five minutes all you could think about, “I need important papers. Birth certificates.” I had a newborn baby. “I need this milk for this baby.” The Similac or whatever it was, the formula for the child. We didn’t even take clothes. Just what we had. I remember my children crying. They wanted their game systems and I’m like, “Listen, I don’t have time for that right now.” Where am I taking a gaming system? Of course, I’m taking my frustration out on my children because I’m homeless with four kids, and these people are throwing my stuff on a truck. I’m looking at four children looking at me like, “What's going on here?” That’s how I found out I was evicted. Of course, they plastered the note on your door, which is another humiliation. Because people that live in the building can walk by and see that this tenant was evicted. It was three something in the afternoon. Children were coming home from school, parents from work, you know what I’m saying? So, it was very humiliating. And my thought was, “Let me get my children away from this because I don’t want them to feel shameful of what’s happening.”

I called my caseworker at the time, and that’s when she told me, “Come to the office.” She gave me the referral to the EAU. Because you couldn’t just show up at the EAU. You needed a referral to get into the EAU back then. And that’s how within those six days we found out that they went in there. I didn’t even know what they did. All I know is that they told them, “Oh, we’ve already rented that apartment.” The service people or the case managers is like, “You just evicted her six days ago. How did you already rent this apartment?” I told them, “At this point, I don’t even want to go back there, okay? I’ve been humiliated. I’m embarrassed. I don’t even know where my belongings are.” There were some sentimental pieces of furniture from my mom that got dragged into this, that were lost, and that I could never get back. Pictures of my children when they were babies, I could never get back. So that’s a whole other mentality you got to go through. You not only have to wonder where’s your stuff at. You got these kids, you got people in this EAU unit telling you, “You got to take your kids to school, or we’ll call ACS [New York City’s Administration for Children’s Services] on you.” But you also got them telling you, “Oh, but if you leave and we call your name, you lose your spot.” So, you’re juggling. What do I do?

I had never been homeless. I was never put in that position before. So, it was a culture shock to all of us. Then they did give me a crib for the baby, but the rest of us had to sleep on the floor. Okay. Rats were running, jumping. Kids crying, kids throwing up. It was an experience. The next step was, in these six days or four days, is when they determine if you are homeless. Because they actually give numbers of people that you might go stay with, who they were willing to pay. I’m like, “Miss, my mom is dead. I don’t have any family. There’s nobody I can call and go live with. And second of all, it’s five of us. Who do you think is going to take five people into their home?” So, you go through that process of being determined whether you’re homeless or not. Of course, I obviously qualified. Then they sent us to Brooklyn. To what they call the Assistance Unit, where they’re going to find you temporary shelter. It was in a hospital in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. So now we in Brooklyn, in this one room, five people, still no clothes. My case worker was kind enough to give me extra stamps to feed the kids and stuff. Food wasn’t the issue. It was the fact that what we were going through. Mind you, kids still haven’t been to school because I’m trying to get us kind of situated.

The case worker comes in… [inaudible] “They [the kids] go to school in Manhattan. That’s where I'm from.” “Oh, well, you have to take them” [, says the casework]. “I’m in Brooklyn, lady. They don’t have no clothes. How am I taking these kids to school?’ “Oh, if you don’t take them to school, we call ACS.” That's what they called it at the time, ACS. So, these are the problems that families go through when they become homeless. You’re trying to juggle that. And I’m getting kids up at five, six in the morning, two-hour commute to Manhattan, to their schools, with a three-month old baby, on a stroller. It was a mess. My oldest son was in fifth grade or sixth grade. He was due to graduate. He went to this school his whole entire life. He was due to graduate this year. Well, now we are in 1995. He was due to graduate. That couldn’t happen here, because we were displaced. The Social Services is like, “Oh, well, we can only give you carfare for a certain number of days. You need to get a bus pass.” These are things you don’t think about when you become homeless. When you first experiencing homelessness, you don’t think about, “How am I going to get these kids back and forth to school?” You don't think about that. But then it sinks in like, “Oh, wow, okay. These kids got to go to school. I got ACS on my back. I got case managers calling me down, asking me stupid questions.” You understand what I’m saying? You don’t think about those things, but you got to get this done.

Long story short, we ended up qualifying to be put in what they called, at the time, a Tier Two Shelter, meaning a shelter for a family. We happen to get into a decent one. Now you remember, you're talking to people and you're hearing horror stories. “Oh, better hope you don't go here.” So, you're afraid for yourself. You're hearing stories about shelters that aren’t nice. But we gotta go through this process. Fortunately, we were put in a decent shelter up here in the Bronx. That's how I was introduced to the Bronx. Never knew nothing about the Bronx. That's when the Bronx came into my life, in 1995. End of 1994 into 1995, we were placed in Nelson Avenue Family residence, that's what it was called, that was the shelter. It was a three-bedroom apartment. Of course, it had its rules, regulations, stipulations. But it was decent. Here we go again with the schooling for the children, right? I'm in the Bronx now, I got to transport these kids back and forth to Manhattan. Case manager, “Oh, but we're not going to get bus passes for the kids.” Okay. “What about me?” “Well, that's not our job to give you carfare to take your kids back and forth to school. You have one or two choices: you can either figure that out or you can transfer your children to the schools in the Bronx, near the shelter.” Now, here comes the second disappointment for my children. Remember, they went to that school, that's all they knew. I had a son that was about to graduate from this school. I had to sit them down and tell them. And of course it's tears, and they're angry at me, and I'm like, “Suck it up. It's not what I want. It's just what we have to do. I can't keep getting up six o’clock in the morning dragging you to school. That's too much.” We made the transition to the Bronx schools. That's how we were introduced to the Bronx.

Yeah [laughs]. It was an experience. Fortunately for my family, because all the paperwork was in order and we really weren't lacking any missing documents or anything. We were approved for what they called Emergency Voucher program, something like that, where we got Section 8 kind of quickly. It was an emergency situation. It would stay that way for a year once we got an apartment, and then once we were in that apartment for a year, it would turn over to full-blown Section 8. Okay. We were very fortunate, and everything was in order and that. So, I was able to go start looking for an apartment maybe four or five months after being in the shelter system.

After being up here in the Bronx, I want to say three months in the shelter system, I get a manilla envelope in the mail. They called me downstairs to get your mail. And I open it up. And what comes out of this envelope? All the rent checks that the landlord did not cash, from my previous address. Yes. Yes. Nine months’ worth of rent checks that he held purposely, purposely, to get me out of the apartment. Of course, I took them and turned them into Social Services, but that was the tactic he used to get me out. And me and my case manager at the time were like, “Wow, he actually did this and got away with it.” I could not believe that those checks—If I didn't see it with my own eyes, I would not have believed it. Every check. You remember Social Services paid two cheques a month on your rent. They pay a portion on part A and a portion on part B. There were nine months of checks there. So, nine times two, was all there. Not cashed, not open, not nothing. That was the first time I understood what being discriminated against meant. I was discriminated against because I was poor. I was living in a decent building, and a greedy landlord wanted that two-bedroom apartment that my mother was only paying $222 dollars a month rent for. Where he knew, due to location, due to the upkeep of the building, he at the time could get a thousand or more for that apartment, a month. And that kind of broke my spirit.

[00:36:32**]**

Zacca Thomaz: Sorry, were those checks sent to you by the landlord?

Statuto: Yes. Yes. It was sent to me. Because he couldn't do nothing with them. And I guess he wanted to show me, “You thought I couldn't get you out. But I did. And here’s your—” I was a tenant on public assistance. He didn't want that. Remember, we're talking, even in 1995, areas were changing. And if you look at Ninth Avenue now, Tenth Avenue now, it is nothing like it was back in the 1980s and 1990s. Now it's all restaurants, you may as well call it Restaurant Row down there in Manhattan. The area was changing. They were bringing yuppies in. I live next to a co-op building. Those people didn't want welfare people next to them. I don't mean to be that blunt to you, but they didn't want welfare people living in their community. You understand what I'm saying? They're here in a co-op, condo paying maintenance fees, mortgages. “You living in this nice building, and you paying $222, where I'm over here paying 1,200 a month?” You understand [laughs]? So that's when I first found that I was discriminated against because I was poor.

Let's go back to 1995. Bill Clinton running, right? And what was Bill Clinton’s promise to the people? Welfare reform, right? Welfare reform. We're going to do something about this. “All these people laying up on welfare, having babies.” But that wasn't really the case. But that's what his agenda was. “We're going to do welfare reform [laughs]. We're going to change the dynamics to welfare reform.” At the time, an organization called Community Voices Heard came into the shelter trying to garner up people to protest welfare reform. I happened to go to one of the workshops, and that's where the organizing and commitment bug caught me. I have four children. I'm in a shelter. You're telling me that I got to go to work for these benefits that you're giving me? You're giving me $187.50 every two weeks, and you want me to go to work for thirty-five dollars a week for that money? “Oh, but the housing—” “I'm not living in a house. I'm in a shelter.” So it kind of caught me and I wanted to fight against it because I just didn't feel that that was right. You were going to impact so many families. And y'all didn't care how it was gonna hurt or affect people. All you knew is that you were going to let these rich people know, “We're not going to be paying this bill anymore for these people.” Because that's basically what it boiled down to: taxpayers’ dollars being used to take care of unfortunate people. And they were crying, “Oh they're having babies. They're getting food stamps.” So, there was a mixed bag. That's what got me involved in welfare reform, with Community Voices Heard.

I'm actually one of the founding members. Community Voices Heard [CVH]. I don't know if you've heard of them in Manhattan. Before they became Community Voices Heard, they were under the umbrella of HANNYS: Hunger Action Network of New York. Where Hunger Action Network of New York was about feeding hungry people. But CVH was an umbrella under them. And they were getting funding to do welfare reform work. We didn't like what HANNYS was doing. We were out here protesting, speaking to funders, getting money to do the work that needed to be done. And HANNYS was taking it and trying to dictate to us what the agenda should be. There were core twelve members. I happened to be one of them. That’s how CVH got started. We decided to take it away from HANNYS, become our own entity, about 501(c)(3) process. Any money raised now would go directly to Community Voices Heard for the work that we do.

I was an original board member when it started. It's been around now for twenty-five, maybe twenty-seven years. But I am one of the founding members of CVH. I've been to Washington. I've been to Albany, I’ve been—you name it, I’ve been. I've spoken to Governor [George] Pataki, when he was the Governor of New York. I spoke at his press conferences. [Former Governor] Mario Cuomo, up in Capitol. Name it. I've been there protesting the fact that you are asking people to work for a check. That some had no work experience, very little education. I'm not saying I fell in that; I fell in a part of that category. But they didn't think it well through. They didn't think about the childcare that would’ve been needed for these children or these mothers. That's who they were targeting, mothers with children. Because the politicians and the one percent rich folks who talk about, “We're tired of taking care of them.” That's when they develop WEP, Work Experience Program. And we were fighting against it. You can't tell me that I got to work twenty-five, thirty-five hours a week while you give me $187.50. You're willing to pay a babysitter to watch my children while I go do the jobs that your city workers are getting paid big bucks for.

It was a big thing back then when Clinton was trying to get reelected with this welfare reform. And he got elected on that welfare reform bill. Let's be real. But they didn't know what they were doing then. They didn't know. They didn't know! The impact it was going to have. People died because you were sending them to parks. You didn't know their health, mental, nothing. Then, when people started getting sick, a couple of people died. They had to pull back. “Wait a minute! This ain’t working here.” Families are suing the city now because you put unprepared people in jobs that other people were getting paid to do. So, they had to re-organize. Remember, when WEB first started, you didn't go to a doctor. You just got an assignment, and you went to the Parks Department. Most of us was pushed toward the Parks Department, sanitation. We out there picking up garbage that you people are getting $21, $31 an hour for. Got us up and down these streets picking up the garbage, while you riding us around with these vests on that says WEP on the back. More dehumanizing, right?

Because that's what WEP looked like back in 1995, 1996. Two people got sick, started dying. They didn't care! All they thought about was this was going to lessen the welfare rolls. They weren't given job education. Some didn't even have high school diplomas. Let's be real, here, okay? So when that started happening, people got sick, or people had medical conditions. They made you jump through hoops to prove that you couldn't do this work. Then two or three people died and they, were like, “Oh, we need to re-look at this.” So that's when they established that, if you're going to receive any type of government funding, you're going to have to get a medical assessment. They send you to a doctor. You with these doctors, you spend three hours there, because you're seeing different doctors. That ain't really assessing your health. They're really not. They're taking your blood, they're asking you a couple of questions. They're basing this medical on what you said. Ain't no real tests being done here. Maybe an EKG, because I've went through it a couple of times. The EKG, some blood tests, eye test.

Then they added this entity of job training, where they send you to these workshops five days a week, nine to five. You hungry, you ain't got no food [laughs]. But you sitting in these classrooms, trying to prepare yourself to get ready for work. I'm not saying that some people didn't need it. But me? I didn't need that. But I had to do it for them to give these benefits. They're supposed to job train you. You're in this program for four months. They're giving you carfare every two weeks. They're not giving you no lunch money, but they're giving you carfare to get back and forth there. If you miss a day, you automatically terminated it. CVH fought over twenty years to get WEP exempt. Finally, it did happen. But it took a span of twenty years that they abused, used, put families in jeopardy, dehumanized people.

We weren't getting jobs in office buildings, or we weren't getting internships in office buildings. We were thrown in the streets to pick up trash, to clean the subway stations. If you look at the data, not many people that went through these doors, got jobs. Remember, this is supposed to be job training, and they were supposed to prepare you to become self-sufficient. Not many of those people that did the train ended up getting hired by the MTA [Metropolitan Transport Authority]. What they don't tell you is—Let’s say you did everything MTA wanted you to do. I'm talking about the transit system in New York, and that was your WEP assignment. You did everything they wanted you to do. You showed up every day. You clean. Now they're looking at to hire you. They don't tell you the background checks. They don't tell you that. I'm talking about these workshops. These people that are running these workshops, trying to prepare you for the job. They don't tell you the paperwork you need to get to get hired by MTA. They don't tell you none of that. They don't tell you that you got to come out of your pocket and pay for if you have an arrest, regardless of whether it's a misdemeanor or not. You gotta pay for those depositions. You gotta pay for that record to prove to MTA that you're not a convicted felon. They don't tell you none of that! But they got you down there cleaning them trains. So those were the discrepancies. You weren't training me for a job. All you were training me do to do was to get up early, come and do your work for you while your people were getting paid and we weren't. We weren't making salaries. Nothing. And you had us in the trains. Remember at WEB we wore an orange shirt like this. Down in the train they had that lime green vest. At the time, you don't realize it's dehumanizing you and humiliating you, because you don't know. But people know, “Oh, that's a welfare worker.” So, they're already forming an opinion in their head about you. That's not who you are. That was my first community organizing or getting a bug of standing up for what I believe in, my time with Community Voices Heard.

June of 1995, we got an apartment, three bedroom apartment in the Bronx. We were approved. I didn't meet the landlord; I met the super of the building. He liked me. And let me tell you, when looking for apartments, I found discrimination there. I found landlords saying, “Oh no, she's a single person. She got four kids. We don't want her in a building. Her children may tear up—" You don't even know us. So that was another barrier that was placed upon me that I wasn't aware of and that I didn't think that I would encounter. But I did. I did encounter that. There was a beautiful apartment. And the owner, up on Paulding Street in the Bronx told, “Oh no, we wanted a husband, a wife, and three kids. She's a single mother with four kids. We don't want her here.” What can I do? Fortunately, we met a super, and he's Irish like me. I'm Irish and Italian. And I guess he took a liking—He said, “Do you want this apartment?” I'm like, “Yes, I do.” I wanted to get out of the shelter. I wanted to give my children some type of normalcy, finally. And he said, “Then don't worry about it. I'm going to call the landlord. This is going to be your apartment.” It still brings tears to my eyes. And we did get the apartment. I never met the landlord. All he did was call and say, “Miss Statuto, that apartment will be yours. We understand you're coming from the shelter system. We will fill out the paperwork. You will have that apartment.” June 15th, 1995, we moved in. To our home, after being homeless for seven months. Because we were homeless from October to June. So anywhere between seven and nine months, we were homeless. So we were, now, we were becoming a little bit more stable.

We had our own apartment again, we didn't have to live by people's rules. I'm still involved with CVH at this point. Still fighting the battles on WEP. Still fighting the battles on the mistreatment, and you asking us, “You want to attack this budget? You want to attack that budget?” And you're not understanding the impact that it’s having on families. It's always the poor people. First, they get the wrong end of the stick. I've heard the rumors and the comments and “Oh, you on welfare, you don't count.” “Yes, I do. Yes, I do. I do count. And just because you may have a little bit more than me don't mean you are better than me.” Remember, back in the 1990s, we were three class of people: low-income, middle-class, and upper-class. Now that middle class is gone. You don't even hear them talk. Remember, everything used to be about middle class, the middle class. Trying to elevate low-income people up to the middle class. You don't even hear that no more. That's not even in the conversation. We have two groups of people now: low-income and the rich. That one percent or two percent of rich people. You got people that are developing in your community that haven't even came and talked to you, or the community residents that are there and ask how they feel about you. They go through the community boards to get their buildings built. None of this comes through the tenants or the residents or the community. That doesn't work like that. Everything goes through the community boards here in New York. We have no say. Even though I am living in a new building, the people before I moved here, nobody in this area had a say about this building going up or who was going to live in here. Let's be real. Went through the community board, they permitted it to come up. You understand what I'm saying, right? They permitted it to be built as long as they donated a certain amount of apartments to a certain amount of people, right? Okay [laughs]. So, you don't have a say.

Thankfully, I'm on a community board now, so I have a say. If I don't think it's beneficial to my community—I could be vetoed out or voted down, but at least you know how I felt about it. And how this is going to impact my community. I'm on a community board now. Community Board 6 in the Bronx. So I have power. I didn't know those things back in 1995. I heard of them things 1994, 1992, I heard about community boards and stuff like that, but I didn't know the impact that they have on communities. Because what runs communities is the community board. Doesn't matter what the police say. Don't matter what the mayor say. Don't matter what the governor say. Nothing gets built in your community without the approval of your community board. Let's get that understood. No projects, no businesses come in your community unless the community board approves it. I sit on this. I see what comes through now. I just got on this community board because I just moved over here, almost three years now. But I didn't know that. I had been involved in CASA. I heard of it. But being involved in CASA is what taught me the community board. “Go for your community board.”

So now, we’re in 1995. We’re home. Everything is good. I'm still involved with Community Voices Heard here and there. Then life changed. I started working. The kids got older; they were in school. I could go back to work. I could be self-sufficient on my own. Great. I saw my building, that I was living in before I moved here, turn over. The landlord that allowed us to come in, sold the property—sold it to some gangsters [laughs]. Actually, to be honest, acted like they were in the mafia. Really, they did. Seriously. They were from Yonkers. They were white boys. You're in a diverse community. Mostly Hispanic and African American, very few white. Okay. We're not in the 1950s and 1940s and 1960s, where the Bronx was Irish and Italian. Let's get that understood. Now we're in a very diverse community. You have a couple of caucasians sprinkled through this. But here come these white boys out in Yonkers.

That's when things started going downhill in that building. When, before they took over, when they did a repair, that shit didn't come back to haunt you. That landlord made sure–well, the super did–that super made sure he repaired it right, and you weren't going to have problems with it later on. Now, here come these boys and they patched, band-aiding. Band-aid repairs. They're only in it for the money. They bought the building, probably for a million and something dollars. They saw a profit there. They had forty-seven families. It was a rent-stabilized building. They had, I want to say maybe a third of the building receiving subsidies. So, they knew that money was guaranteed every month, regardless of what the tenant was doing. But they knew that that money was guaranteed because they saw in the rent rolls who was receiving subsidies. “Oh, this looks like a big deal here.” But then when you're not taking care of your building, things start to happen. The super of that building passed away. He was the super there fifty-something years. He passed away, and they brought in another super, who wasn't dedicated to the building like the previous super was. He would do patchwork. Slap it. Three months later, we back with the same problem. What we didn't know going on behind the scenes: these boys from Yonkers was taking tenants’ names and applying them to other buildings to get subsidies. They went to jail and everything [laughs]. The building ended up in foreclosure. They found out that they had duplicate tenants. Not the ones that was receiving subsidies here, [the] ones that weren't. And they had people, I guess, inside Social Services getting the money on rent that wasn't even owed. It all came out. They ended up getting arrested. The building went into foreclosure. They ended up going to jail. Their attorney even went to jail because she was part of it.

In comes the new landlord, I guess, who saw the lot of buildings, bought it up, and he steps in. This is in 2009. His name was Abdul Khan. Now mind you, I've been in this building since 1995. We're now in 2009. Me and my children are comfortable. Children are graduating high school. Some are going off to college. We're living. Here comes this new landlord. Indian descent. When he came, there was a lot of stuff going on in the building. There were people in apartments that didn't belong in them; people that were squatters, whatever. He comes in gung ho: “I'm going to find out who these people are who don't belong here. They’re gonna have to go.” But he didn't come to us as human beings. He came to us as a gestapo. “Who are you? Show me your paperwork!” “Wait, what? Who are you?” Yes, we did receive court papers telling us that “the building has been sold. This is the new landlord, yada yada yada.” But they hadn't introduced themself to us yet. And when they came to introduce themself to us, they didn't come in a friendly manner. They came gestapo. “Who are you?” Banging on doors? “I will evict you.” And me? My mouth? I slammed my door. “Don't talk to me like that, first of all. You want to have a conversation with me about this apartment, we can do that. But if you're not going to tell me ‘Who are you? Show me your ID.’ I don't even know who you are. Why would I show you my ID?” Things like that. He was a piece of work [laughs]. He was a piece of work. The super that came with the Italian boys was still there. He kept that super. But that super wasn't really repairing things. He was doing patchwork. And here comes this new guy. He kind of got out, weeded out the people that didn't belong near to the people that did belong. But he wasn't taking care of his building. We were many days in the winter, no heat, no hot water, boiler breaking down, rats. You name it, it was happening. You tell him about it, very minimal was done. Very minimal was done.

I'm going to move this along to 2017. I was at work. I don't know where I was. My son, texts me, “What's wrong with the gas? Stove not working.” So, I hit up the super. By this time, we had all developed a rapport with the super, because he'd been there through the struggles with us. Hitting him up. “What's going on? My son is saying the stove is not working.” We did not know. This was September 5th, 2017. Gas was shut off by ConEd, but we didn't know. Nobody seemed to want to tell us what was going on. Of course, most of us tenants started calling ConEd, “What's going on? Why we don't have no gas?” ConEd basically told us, “There was a gas leak, and we turned off the gas. Any other information we cannot give you. You have to get that from the management.” Well, management, landlord wasn't willing to tell us what was going on. But we as tenants got together and said, “What can we do? We have to find a way to fight back against this. We have no gas.” [interruption] All of us got together in the lobby, “What can we do? How can we live with no gas?” And the landlord is not answering us. The super is not really giving us no answer. Talking about all is going to be fixed in a couple of days. Well, a couple of days? Now we're in October, we still have no gas. Nobody's talking to us. Nobody's telling us nothing about this. What's going on here?

I used to walk by CASA every day, because I used to watch my granddaughter while her mom and dad worked. My daughter and her husband work, so I used to babysit the granddaughter. And I walk by CASA every day. So, I suggested to the tenants, “Listen, there's this organization called CASA. Let's call them.” We looked them up online and basically saw that they do housing rights. Inform tenants about what their rights are, yada yada yada. “Well, let's bring them in and see what they can tell us and what we can do.” That's how I got involved. That's how CASA was introduced to me. We went to them. We asked them to come to the building to do an educational tenants’ rights, informational tutoring. They came. They told us about our rights. They heard our cries. Our main cry was we had no gas, and we weren't being told why. They asked us if we were willing to organize a tenant association and fight back against the landlord. At this point, everybody was. We had about more than half the building willing to, because nobody had gas. They stepped in and gave us these little ten-dollar hot plates from P.C. Richard. But yet they still weren't telling us why we have no gas! Through CASA organizing us and us willing to start a tenant association is how we learned why the gas was shut off. His property, his building, he had the right to switch its heating mechanism. He went from oil to gas. But when he had the plumbers do the work, they weren't licensed plumbers. And they didn't get a permit from the city or nothing. He just had a plumber go in there and install some piping, and switch the heating mechanism from oil to gas, which would decrease the meter in the hot water and heating system. So that we could stop complaining about that. I don't think that worked very well. But anyway, whatever that plumber did, gas started seeping and that's why ConEd shut it off. They found out that it was an illegal transformation. There were no permits and so they shut it off. Now, once ConEd is involved, and the fire department involved, this shit ain't coming back on until it's up to code. That's what started us organizing in our building.

Right away my tenant association skills came back from when I was living in Manhattan. And being boisterous about, “We no longer can sit around and allow a landlord to collect rent money, subsidies money, and be treated like this. Enough is enough.” And we went after him. And we went after him hard. We took him to court. We won two abatements against him. We won a DHCR [New York State Division of Housing and Community Renewal] order against him. And then we ended up getting a building taken from him.

That's how hard we fought to bring him to his knees. Through all of this, he wouldn't meet with us. CASA and elected officials forced him to come have a meeting with tenants. Mind you, this meeting with tenants was in 2018, in August. We lost gas September 5th, 2017. He didn't meet with the tenants until August of 2018. He came because he was pressured to come. There was press there, the Borough President now of the Bronx was there when she was a counselor, and we had support. Because we were fighting. “We're here with no gas and they're not doing nothing. We're spending money out of our pockets to eat.” Because everybody gets tired of them hot plates. When he came to meet with us—He didn't address us very nice: he called us animals. He said, “you animals.” Animals? Oh, okay, here we go being dehumanized again. Being humiliated again. You're calling us animals in front of elected officials, in front of the press, and just to our faces. You have no regard to what you have put us through thus far. So, fines kept hitting him, took him to court, made him settle two abatements, one was twenty-five percent, one was fifty percent. And then we brought DHCR in and got a rent reduction, which is still in place today. That was back in 2018,19. The rent reduction. Here we are in 2023, and the rent reduction is still in place today.

That's what got me involved with CASA. I started going to meetings and heard about–before this even Eviction Free [Bronx campaign] came up. Eviction Free just really started because of the pandemic and what is going on now. A lot of the work was around MCI, Major Capital Improvement, Rent Guideline Board, and just informing tenants about their rights and how they can fight back against predatory landlords. I think my most—work that I'm proud of is–and plus they were sponsoring the RTC, Right to Counsel–was the work that we were doing with Right to Counsel and RGB work. Standing up and letting nine [RGB] members know that, “You don't live in my community. You don't understand what's going on in my community. You don't understand. You're not the landlord. You're probably a landlord to some other property, but you're not the landlord. What landlords are getting away with in court—” And the RTC. Had Right to Counsel been involved in around 1994, I would’ve never been evicted from my apartment, from my mother. I would’ve never lost special things that I can never get back. Because I would’ve had an attorney to represent me, and they would've walked me through what was going on. But these many years later, it is available now to people who are facing predatory landlords, who are going after them for rent money or trying to build up.

So those are the campaigns. The MCI campaign, Major Capital Improvement, where landlord can say that he's made improvements to the building, like fixed the roof or put in a new elevator or gave everybody new stoves. Very little inspection is done to see if that work was really done. A Major Capital Improvement is applied back to the tenants. Depending on how many bedrooms you live in, or how many rooms in your apartment, will determine how much more rent the landlord could charge you if DHCR approves the Major Capital Improvement. So, at the time, let's just say I was living in a three-bedroom apartment. He could’ve charged me twenty dollars each extra for those three bedrooms. So instead of—let's just say—I'm paying seven hundred dollars a month, I would have to pay $760 a month. Major Capital Improvement doesn't go away if I move out, it goes down to the next tenant that's coming in. They don't even know this. So the work that was being done around Major Capital Improvement and how you landlords were using this to prey on tenants, and there wasn't really much you could do about it because DHCR approved for them to get this Major Capital Improvement. So, fighting against allowing that to happen, and there being stricter laws and more inspections going on instead of you just saying, you did this and you didn’t.

Right to Counsel. When I first heard of Right to Counsel, I remember the first meeting I went to. They had what you would call a “mock eviction.” Very first meeting. I'm a very boisterous person [laughs]. They were doing a mock eviction, and I happened to be the marshal. I volunteered to be the marshal [laughs] evicting a family. One thing you'll know about me, I like to play devil's advocate. I want you to see both sides of this coin. It brought back up what happened to me. Although they weren't belligerent to me, but they were rude. “You have five minutes to go and get what you can. Do not touch anything. Do not try to break anything.” You know, things like that. So, I'm on that. It took me right back to my eviction. I played the marshal and I'm going to come along and evict this tenant. And basically, there were other tenants that were going to blockade me, like “We're not going to let you do this. We're going to help this tenant. We're going to see if we can reason with the landlord.” Things like that. But my job as the marshal is to come in, and we're going to evict this tenant.

So that was my first introduction of Right to Counsel. I didn't know all that it entailed. Even though I went through an eviction, I didn’t know that people were being—I don’t wanna say I didn’t know, but it wasn't in my vision. People were being preyed upon, evicted from their homes, and things like that. Didn't think about housing court as far as tenants having an attorney. We always think about an attorney being available when you're in a criminal case. We don't think about it when you're in a housing court case, but it made a lot of sense. So, the fight with getting RTC, which was already on the books, already signed into law in 2014 and that's how we were able to bring this case against that landlord. Khan. His name was Abdul Khan, where we ended up getting him to lose his building. That's the “animals” you called us. That's how powerful we were, the animals you called us. I'm sure he's regretting that today because, of course, the building went into foreclosure. He lost the building.

And now we have a new clown that's in place. He doesn't want to talk to tenants. He asks very condescending questions like, “Do you have a job?” What difference does that make? He asks us questions like, “Are you smart?” So, what are you calling me, stupid? We hear things like tenants call them about repairs. And first thing he wants to know, what apartment you're calling from. You give them the apartment number; he brings it up in the computer. Let's just say there's some rent owed, “Oh you owe us.” “I didn't call you about the rent I owe you. I call you about what's going on in this apartment.” He tells you, “I don't want to hear about that until you have some rent money for me.” Excuse me? So now that we're fighting back in that building to take that landlord to court for predatory practices. For predatory practices.

If you know anything about succession rights, which I didn't know, but I learned through CASA. My son had a right to my apartment on 1515 Selwyn Avenue, because he lived there twenty-seven years. I lived in that building twenty-seven years. My son lived there with me. One of them, anyway. So, when I left, I left that apartment to my son. Three-bedroom. I can tell you what’s getting under their skin. It's a three-bedroom apartment. It's on the first floor and it's in the front. And my son is paying $791.24 a month rent. I know what's getting under their skin. They don't want to recognize succession rights. Not my problem. He has a right to the apartment. Even when I moved, we notified you that I moved. My son is taking over the apartment. My son will pay the rent, which he does. He [the landlord] doesn't want to hear that. He's already dragged me back into court. So, he's another predatory landlord. He doesn't want to talk to us. He asks you questions like, “Do you have any common sense?” Excuse me? He tells you, “Don't you dare call 311. You better call me.” “But wait a minute, don't threaten me. Do you know who you're talking to?” First of all, maybe you need to look up my name. Because the last landlord that we took to court for this building, my name was the first name on that case. Look it up. I don't think you know who you messing with.’

So now we're in the process of going back to court because he doesn't want to recognize the DHCR order that is still in place today. He talks very condescending. He doesn't care about no repairs or anything like that. All he cares about is rent money. The building is in foreclosure. Already. He's only been a landlord a year. He took over the building last year. I think the previous owner, Khan, I think that's where the foreclosure comes from. Because the bank was trying to sell the note before Khan got rid of the building. So now this new landlord is trying to get around it. He's trying to get money from another bank to pay off this foreclosure, so that the foreclosure doesn't happen. Because he kind of sees maybe a profit in the building. I don't know what it is, but we're back meeting with lawyers, about to take him back to court. He didn't recognize the DHCR order. One thing I don't understand is that, nowadays, landlords, when they send you your rent receipt—well, here in New York, I don't know how it is in Amsterdam—but here in in the five boroughs, or at least for me, it doesn't show when you paid last month's rent. Like that balance is never there. So, you never see that, “Yes. You paid April's rent. Zero balance here, and here's May's rent.” It doesn't say that. The two abatements that we won against Khan was never applied when Khan was the landlord. He doesn't want to recognize that. Whether he understands it or not, he says that has nothing to do with him. But it does. You bought the building; you bought the problems. The abatements need to go moving forward.

So now that's what we are. We are reorganizing again. Actually, we had a meeting last night. And I'm not even a tenant there. I just go because of my son. My son doesn't understand these things. So that he keeps the home he has and he's always known, I attend the meetings, and I make sure that he's not going to be pushed out of his home. He works, he pays his rent, he has a right to the apartment, through succession rights. He’s my son. He was on the lease when I moved in. He has a right. He's been there twenty-seven years. So that's why I go over there and get involved in this process again. And remember, the abatement was under my name, the DHCR order was under my name. The landlord doesn't want to recognize this.

What do I see moving forward? Right to Counsel statewide. It is so important. It is so important. People are being dragged into court now. And, like I told you, landlords accepted ERAP, Emergency Rental Assistance Program, which was their little band-aid to help people that were impacted by a pandemic that they had nothing to do with. This pandemic was thrown on us. We were not prepared. Let's be honest. We weren't prepared. We were nowhere ready for what was going to happen, and it impacted people's lives very much. People lost family members, loved ones, couldn't bury them, couldn't see them in hospital. A gamut of things that happened in the last three years. Especially when we were right in March from 2020 and 2021. The number just kept going and going and going and going. We didn't know where we were going.

They came up with this package that they presented to the American people that was going to kind of fix things, the PPP [Paycheck Protection Program], the unemployment, these little things that they thought they put in place that was going to sustain people. But if you weren't working, you weren’t entitled to unemployment. If you were on any type of government assistance, you really didn't get anything extra besides those stimulus checks. If you were on SSI [Supplemental Security Income] or anything like that, you didn't get that much extra. People on unemployment were getting unemployment plus six hundred dollars or whatever it was. All these little band-aids that they put together to kind of sustain people. But we have to understand also, they didn't know what they were dealing with. They were just trying to throw money at the problem, and it wasn't working. So here comes this ERAP program, Emergency Rental Assistance Program, for people that weren't able to pay rent. We're going to pay fifteen months, twelve months plus three months ahead. Kind of give you a little footing to get yourself together. But that's not what happened when ERAP rolled out. ERAP didn't pay fifteen months. ERAP paid six months, five months, eight months, it never paid a full fifteen months, giving the people the stability they needed. People shouldn't have had to re-apply twice, two, or three times for ERAP. Because you told us, you told the American people, “You apply. We find you acceptable: we're going to pay twelve months back, three months forward.” It didn't happen like that. Landlords were getting the money. Still, rent was being owed. People still weren't working.

People lost their job permanently. My daughter was one of them. She was a teacher. She refused to get vaccinated. Her body, her choice. She chose not to get vaccinated. She never caught covid. She never caught covid. She never tested positive for covid and neither did I. Now, don't get me wrong, I did get the two vaccines. Because of my age, not because the government was pushing it, pushing it, pushing it. I'm sixty-three years old. I got to protect myself against other people. My immune system isn't as healthy as yours might be. I'm a little bit older. I don't have any underlying conditions, but I didn't want to be out there fighting, woo, woo, woo [laughs]. So I did get the two vaccines. My body, my choice. She chose not to. Lost her job as a teacher, certified, tenured, and everything. Certified special ed teacher, had tenure, and lost her job. People weren't recognizing this. You were pushing mandates on people that shouldn't have been mandated. When my daughter became a teacher, she signed a contract with the Department of Education. The Department of Education did not require vaccines or these mandates. They didn't care.

Back to ERAP. They didn't do what they were supposed to do. They were paying small portions of rent. People were re-applying. Landlords accepted the money. There were stipulations. Some of the stipulations was, “You can't raise their rent for a year. You can't take them [tenants] to court for a year. If you accept this money from us.” Well, that's not what's happening now. Remember some of the last payments went out in 2022. We're almost at the halfway mark of 2023. Let's talk about the payments that went out in September of 2022. We're not at that year mark yet. Why are you dragging these tenants into court if they still owe you money? Why? That's not what you agreed to when you accepted that ERAP money. And the courts are taking it. And they're not accepting the guidelines that were set forth. They're ignoring and letting these landlords take these people to court and demanding money. For back rent. When ERAP should have took care of that back rent. So now we're in a housing crisis. We got landlords trying to get rid of people. We got landlords that want these apartments to up the rent because rents are crazy.

For my son's apartment, he could easily get $2,200 a month. Easy! Three bedrooms? First floor? Front window? Easy. And that's what landlords are looking for. They're not looking for if the tenant is safe, comfortable, and happy. They're just looking for the profits they make. Another thing they don't do, is they don't allow these landlords to open up their books to see the profits, the margins here. What was your profit? What was your losses? We don't see none of that. We don't know personally how you're doing. What we do know is you're not paying water bills because we get notices in our mailbox about that. We know what we do know. You're not paying the light bill for the common area because we get letters in our mailboxes for that. What are they doing about that? They're not doing nothing. But the moment I owe you three months’ rent, you can drag me into court. Why are you not dragging him into court for their water bills, City? Why are you not dragging them into court, ConEd, for not paying light bills? Why should tenants be getting light bills, threatening to turn off lights in common areas that they're not responsible for? And those bills are looking at five thousand, six thousand, seven thousand. What is being done to them for that? Nothing. Nothing. Yet, you're allowing them to drag us into court for some money owed to you, that at this point, when we asked, “Cancel Rent,” that's what they should have done. Bail them out, because you bailed the housing crisis out. Cancel that rent and we wouldn't be in this pickle that we're in today. Y'all created—the government created this housing crisis. When we were fighting for Cancel Rent, you should’ve canceled it. You should’ve made a private deal with these landlords. We'll give you this amount of money to hold you over. Now you've got tenants being dragged into court, being asked to give money that they don't have. Go for a One Shot Deal, so when they get their tax return, the government can come and take that from them because they needed help. Chaotic.